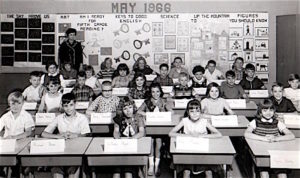

As I approach the far shore of middle age, I can now say without exaggeration that I remember a fair number of things that happened a half-century ago. It feels more than a little bit strange to use that resonant phrase with reference to myself, but it’s nothing more than the truth: I was born sixty years ago, which means that I was ten years old in 1966, old enough to have already accumulated a good-sized scrapbook of memories.

As I approach the far shore of middle age, I can now say without exaggeration that I remember a fair number of things that happened a half-century ago. It feels more than a little bit strange to use that resonant phrase with reference to myself, but it’s nothing more than the truth: I was born sixty years ago, which means that I was ten years old in 1966, old enough to have already accumulated a good-sized scrapbook of memories.

To be sure, anyone who unquestioningly trusts the accuracy of such youthful memories is a fool. I like to think that I’ve retained a few brief flashes that predate my kindergarten days, but I suspect that most of them are in fact derived from the innumerable photographs and home movies that my father took when I was a little boy. As for my awareness of the world beyond the city limits of Smalltown, U.S.A., it started with the assassination of President Kennedy, of which I do have one verifiable first-hand memory: I still have a startlingly sharp mental picture of Jackie Grant, my second-grade elementary-school teacher, telling her students that the president of the United States had been shot and killed in Dallas, after which we were all sent home.

That indelible moment is, however, one of a bare handful of my early recollections of life in the larger world that isn’t an echo of something I watched on TV. I am a member of the first generation of Americans who grew up with television and took its existence for granted. What I saw on the small screen seemed perfectly real to me. Eleven months after the Kennedy assassination, I saw Louis Armstrong on TV for the first time, and I have no doubt of the exact verisimilitude of my memory of that life-changing event, which I described in the afterword to Pops:

That indelible moment is, however, one of a bare handful of my early recollections of life in the larger world that isn’t an echo of something I watched on TV. I am a member of the first generation of Americans who grew up with television and took its existence for granted. What I saw on the small screen seemed perfectly real to me. Eleven months after the Kennedy assassination, I saw Louis Armstrong on TV for the first time, and I have no doubt of the exact verisimilitude of my memory of that life-changing event, which I described in the afterword to Pops:

I thank my mother, who called me into the living room of our Missouri home one Sunday night and sat me down in front of the TV, on which Louis Armstrong was singing “Hello, Dolly!” on The Ed Sullivan Show. “This man won’t be around forever,” she said. “Someday you’ll be glad you saw him.”

So I was—and am.

That happened on October 4, 1964. I turned ten a year and a half later, at which point the half-opaque veil of the past naturally becomes more transparent. I remember quite a lot about my ten-year-old self and the town in which I lived—but not much about the rest of the world. Just the other day I looked up Wikipedia’s timeline of events in 1966, thinking that I might find a bit of fodder for a Wall Street Journal column about the fiftieth anniversary of something or other. It was, not surprisingly, an eventful year, but I was struck most forcibly by how little I noticed at the time about its most consequential occurrences. Nineteen sixty-six was, among many other noteworthy things, the year in which Lenny Bruce, Montgomery Clift, Alberto Giacometti, Hans Hofmann, Buster Keaton, Evelyn Waugh, and Clifton Webb died, but I didn’t yet know who any of those men were.

As for Julie Manet, who died on July 14, I knew nothing of her then or for many decades to come. It certainly would never have occurred to me that an etching of Édouard’s beautiful niece would be hanging in my New York apartment fifty years hence, much less that I would even have a New York apartment. In 1966, and for several more years afterward, I took it for granted that I would spend the rest of my life in Smalltown, U.S.A.

As for Julie Manet, who died on July 14, I knew nothing of her then or for many decades to come. It certainly would never have occurred to me that an etching of Édouard’s beautiful niece would be hanging in my New York apartment fifty years hence, much less that I would even have a New York apartment. In 1966, and for several more years afterward, I took it for granted that I would spend the rest of my life in Smalltown, U.S.A.

The main thing I remember about 1966 was the death of Walt Disney, an event that was by definition a big deal for a child of ten. Everything else that happened that year pales by comparison. I recall nothing of the opening of the Metropolitan Opera House, for instance, or Ronald Reagan’s election as governor of California, nor did I take note of the release of Blonde on Blonde and Pet Sounds. As for Miranda v. Arizona, in which the Supreme Court ruled that police must inform suspects of their constitutional rights before questioning them, I heard about it only because Dragnet, my father’s favorite TV show, soon made a point of incorporating Miranda warnings into Joe Friday’s dialogue.

Not surprisingly, it is my TV-related memories of 1966 that stand out most boldly, if imperfectly. That was the year in which The Dick Van Dyke Show, another family favorite, was canceled, but I can’t recall saying “Gee, I wonder what happened to Rob and Laura Petrie”? What I do remember with undiminished clarity was the premiere of another series, Star Trek, to which I soon became hopelessly addicted. I also have no trouble remembering the first showing of Chuck Jones’ TV version of How the Grinch Stole Christmas, which I loved then and still love now.

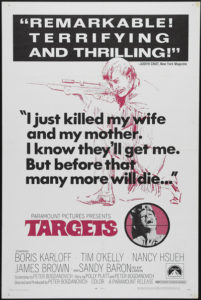

I do, however, remember one national news story with unexpected clarity. On August 1, Charles Whitman took a rifle to the top floor of a tower at the University of Texas and used it to shoot and kill 14 strangers, having previously murdered his wife and mother that morning. As I watched the news that night, I was haunted by the notion that one man could kill so many people, not knowing that I would live to see such horrors become commonplace, or that Peter Bogdanovich would use this one as the inspiration for a movie released two years later whose cast included Boris Karloff, the genial voice of the Grinch.

I do, however, remember one national news story with unexpected clarity. On August 1, Charles Whitman took a rifle to the top floor of a tower at the University of Texas and used it to shoot and kill 14 strangers, having previously murdered his wife and mother that morning. As I watched the news that night, I was haunted by the notion that one man could kill so many people, not knowing that I would live to see such horrors become commonplace, or that Peter Bogdanovich would use this one as the inspiration for a movie released two years later whose cast included Boris Karloff, the genial voice of the Grinch.

As for the rest of 1966, it slipped past me. It wasn’t until 1968, the year that Allan Bloom would later describe as postwar America’s annus horribilis, that I started paying close and consistent attention to the world beyond the city limits of my tranquil home town. That was the year in which the contented unknowing of childhood that Philip Larkin described in “MCMXIV” came at last to a bloody end:

Never such innocence,

Never before or since,

As changed itself to past

Without a word—the men

Leaving the gardens tidy,

The thousands of marriages,

Lasting a little while longer:

Never such innocence again.

* * *

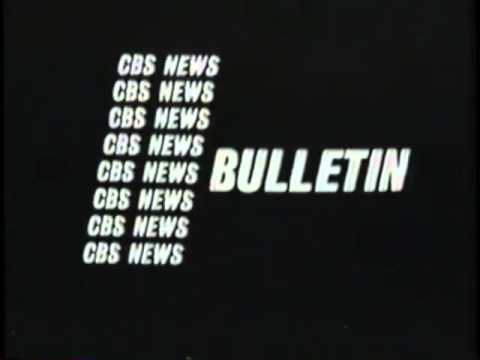

The opening of NBC’s Huntley-Brinkley Report on August 1, 1966, in which Chet Huntley reports on the shootings in Austin, Texas:

A scene from Targets, directed by Peter Bogdanovich: