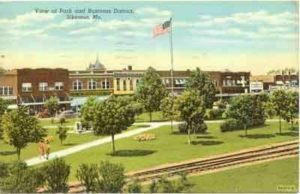

I was nosing around Facebook the other day when I stumbled across a reproduction of a picture postcard that bore on its face an ancient black-and-white photograph of the first church that I can remember attending. Smalltown’s First Baptist Church, an imposing brick structure not far from the business district, was built in 1915. My family worshipped under its roof every Sunday in the early Sixties until my father decided to take his theological trade elsewhere. It was there that I was informed by a Sunday-school teacher of the nonexistence of Santa Claus, a revelation that reduced me to tears.

I was nosing around Facebook the other day when I stumbled across a reproduction of a picture postcard that bore on its face an ancient black-and-white photograph of the first church that I can remember attending. Smalltown’s First Baptist Church, an imposing brick structure not far from the business district, was built in 1915. My family worshipped under its roof every Sunday in the early Sixties until my father decided to take his theological trade elsewhere. It was there that I was informed by a Sunday-school teacher of the nonexistence of Santa Claus, a revelation that reduced me to tears.

A decade later the congregation built a new church on the edge of town, and the old one was deconsecrated (if that’s what Southern Baptists do) and converted into an all-purpose community center whose sanctuary became the home of Smalltown’s Little Theatre, of which I was by then a loyal member. I performed in The Fantasticks and Fiddler on the Roof in the same grand chamber under whose roof I had once listened squirmingly to sermons that seemed to go on all morning. In due course the Little Theatre found itself another, better place to perform, and the crumbling brick heap—for that, sad to say, was what the building had finally become—was razed a quarter-century after that.

In between those two events, I paid a short visit to the old First Baptist Church, an event that I would later describe in a book about growing up in Smalltown:

We passed through a locked door and into a long corridor, the corridor that runs along what once was the backstage wall. Next to an Alcoholics Anonymous bulletin board is a broad brown metal door, and it, too, is kept locked. I pulled the door open and walked down three brown-tiled steps to what once was the baptistry of the First Baptist Church and which later became the stage of the Sikeston Activity Center. Now the steps lead down to nothing: no pews, no chairs, no stained glass, no congregation, no audience. Pails and buckets line the walls. The plaster is peeling. An abandoned pool table stands in the center of the room. Only the rake of the floor and the faintly ecclesiastical hue of the moldings give any hint of what this room once was; only the still-hanging stage curtains suggest its later uses. I looked around for a moment. Then I excused myself and fled as quickly as I could from the musty air of the sanctuary into the heat of a summer day.

My visit to that empty room jolted me, though I tried to pretend that it was less disturbing than I knew it was. “The grip that my home town has on me is rooted above all in its changelessness,” I wrote in my book, and I believed at the time, or pretended to believe, that I knew whereof I spoke:

The First Baptist Church of Smalltown, Missouri, was still the First Baptist Church of Smalltown, Missouri, when the sign outside read SIKESTON ACTIVITY CENTER…The black plastic letters on the façade are gone and the chiseled granite letters that say FIRST BAPTIST CHURCH are visible once more, and they will be visible as long as the church stands, and even after the church is torn down and the rubble carted away, there will be books and pictures and memories to prove that it once stood on a lot just across the railroad tracks from downtown Smalltown.

Maybe so, but the postcard that I found on Facebook is the only picture I’ve ever seen of the old First Baptist Church, and I haven’t been able to track down any others online. Nor is there any way for casual passers-by to know that a church once stood at the corner of South Kingshighway and Greer Avenue. Having been reduced to rubble and, shortly thereafter, an empty lot, the church—or, rather, the site on which it stood—is now the home of Smalltown’s police station. (Irony duly noted.) While the design of the new building was clearly intended to suggest the old church, I can’t help but wonder how many of Smalltown’s present-day residents are aware of that fact.

Maybe so, but the postcard that I found on Facebook is the only picture I’ve ever seen of the old First Baptist Church, and I haven’t been able to track down any others online. Nor is there any way for casual passers-by to know that a church once stood at the corner of South Kingshighway and Greer Avenue. Having been reduced to rubble and, shortly thereafter, an empty lot, the church—or, rather, the site on which it stood—is now the home of Smalltown’s police station. (Irony duly noted.) While the design of the new building was clearly intended to suggest the old church, I can’t help but wonder how many of Smalltown’s present-day residents are aware of that fact.

As for me, I’ve only been back to Smalltown a couple of times since my mother died four years ago. Once you’ve lost both of your parents, it’s likely, perhaps inevitable, that your home ties will loosen. But I’m as close as ever to David and Kathy, my brother and sister-in-law, and it also happens that of late I’ve been feeling more than a little bit homesick.

As for me, I’ve only been back to Smalltown a couple of times since my mother died four years ago. Once you’ve lost both of your parents, it’s likely, perhaps inevitable, that your home ties will loosen. But I’m as close as ever to David and Kathy, my brother and sister-in-law, and it also happens that of late I’ve been feeling more than a little bit homesick.

I’ve always known that I will probably never again spend more than three or four days at a time in Smalltown—though stranger things have certainly happened to me—but that doesn’t mean I’m any less strongly attached to my home town, or to 713 Hickory Drive, the half-century-old ranch house where I grew up and in which David and Kathy now live. Alas, much of the rest of Smalltown looks very different today than it did when I went off to college four decades ago. Many of the buildings that were important to me as a boy, like the old First Baptist Church, no longer exist, and others have been altered almost beyond recognition.

Nor are there many people living in Smalltown who knew me when I was young. Virtually all of the friends of my schooldays have moved on, or died. I find it almost impossible to believe that I’ve outlived the closest male friend of my youth by a decade and a half. I’ve even outlived the maple tree in the front yard of 713 Hickory Drive, which fell victim to a brutal ice storm and was replaced by my brother seven years ago. Smalltown turned out to be “changeless” only in my mind, and my “home” is wherever Mrs. T happens to be at any given moment, be it Manhattan or rural Connecticut or Sanibel, Florida. I’ve become, as I wrote in this space a few years ago, about as close to rootless as you can get.

Nor are there many people living in Smalltown who knew me when I was young. Virtually all of the friends of my schooldays have moved on, or died. I find it almost impossible to believe that I’ve outlived the closest male friend of my youth by a decade and a half. I’ve even outlived the maple tree in the front yard of 713 Hickory Drive, which fell victim to a brutal ice storm and was replaced by my brother seven years ago. Smalltown turned out to be “changeless” only in my mind, and my “home” is wherever Mrs. T happens to be at any given moment, be it Manhattan or rural Connecticut or Sanibel, Florida. I’ve become, as I wrote in this space a few years ago, about as close to rootless as you can get.

What is it, then, for which I find myself so unappeasably homesick? David and Kathy, of course—not a day goes by that I don’t think of them—as well as my mother and father, whom I loved with all my heart and whose deaths left a permanent hole in my life. Life has taught me that the loss of a loved one is something you never, ever get over. You learn to live with it, but that’s all.

Right now, though, I think that I miss most of all a place that no longer exists save in the unfathomable precincts of memory, the Smalltown of fifty years ago. I can see it whenever I close my eyes, but I long to walk among its shadows, and I don’t know when I’ll get the chance to do so again. At present my beloved Mrs. T and my work, which between them are the wellsprings of my life’s meaning, have more urgent claims on my attention. For now I guess I’ll have to settle for phone calls and faded postcards plucked from the web.

Right now, though, I think that I miss most of all a place that no longer exists save in the unfathomable precincts of memory, the Smalltown of fifty years ago. I can see it whenever I close my eyes, but I long to walk among its shadows, and I don’t know when I’ll get the chance to do so again. At present my beloved Mrs. T and my work, which between them are the wellsprings of my life’s meaning, have more urgent claims on my attention. For now I guess I’ll have to settle for phone calls and faded postcards plucked from the web.

* * *

A scene from David Cromer’s production of Thornton Wilder’s Our Town, remounted in 2014 by Kansas City Repertory Theatre and featuring Linsey Page Morton and Derrick Trumbly as Emily and George:

A scene from You Can Count on Me, written and directed by Kenneth Lonergan and starring Rory Culkin, Laura Linney, and Mark Ruffalo: