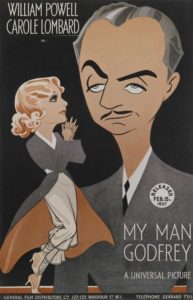

Mrs. T and I opted last Monday to watch a William Powell comedy, My Man Godfrey, instead of subjecting ourselves to the first presidential debate. When I tweeted about our decision, these responses were immediately forthcoming from two of my followers:

Mrs. T and I opted last Monday to watch a William Powell comedy, My Man Godfrey, instead of subjecting ourselves to the first presidential debate. When I tweeted about our decision, these responses were immediately forthcoming from two of my followers:

• “It was a different universe in which a man like that could be a major star.”

• “Released 80 years ago this month!”

The first of these comments immediately put me in mind of something that I wrote about Humphrey Bogart a few years ago in an essay called “Humphrey Bogart, Grown-Up”:

Not all the films he made from High Sierra onward are of equal merit, but Bogart’s performances even in the least of them continue to show successive generations what a full-grown man looks like. In an age that consistently values smooth-faced charmers over tough-minded realists, it is not merely refreshing but inspiring to spend time in the company of a man who, as V.S. Pritchett wrote of Sir Walter Scott, “faces life squarely” and “does not cry for the moon.” Whatever he was like in the world outside the soundstage, Humphrey Bogart was that kind of man on the screen.

William Powell was that kind of man, too. Even though he specialized in light comedy, at which he was an unrivaled virtuoso, his sardonic screen persona had an underlying weight and maturity that made it possible for him to bring off dramatic roles no less convincingly. Without it, he couldn’t have played the tricky role of Godfrey, a homeless man who suddenly finds himself serving as butler to a family of wealthy, irresponsible eccentrics, in the process leaving us in no doubt of his contempt for their lightmindedness (“I was curious to see how a bunch of empty-headed nitwits conducted themselves”).

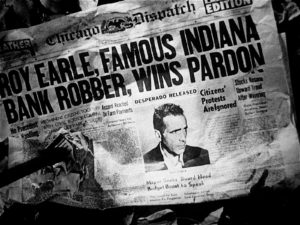

Humphrey Bogart was similarly mature, even as a young man, and his maturity is what propels High Sierra, in which he plays Roy Earle, a weary gangster with graying hair who was even older on the screen than Bogart himself was in real life. His performance is redolent of the terminal disillusion of a man who has seen the worst of Depression-era life and been permanently scarred by it. I doubt that very many of today’s American screen stars could play such a part other than ludicrously, but Bogart, who was forty-one when High Sierra was filmed, brought it off without apparent effort. To watch him in High Sierra, or Powell in My Man Godfrey, is to understand the truth of my friend’s remark. We live in a different universe now, one in which maturity is not merely undervalued but actively shunned.

Humphrey Bogart was similarly mature, even as a young man, and his maturity is what propels High Sierra, in which he plays Roy Earle, a weary gangster with graying hair who was even older on the screen than Bogart himself was in real life. His performance is redolent of the terminal disillusion of a man who has seen the worst of Depression-era life and been permanently scarred by it. I doubt that very many of today’s American screen stars could play such a part other than ludicrously, but Bogart, who was forty-one when High Sierra was filmed, brought it off without apparent effort. To watch him in High Sierra, or Powell in My Man Godfrey, is to understand the truth of my friend’s remark. We live in a different universe now, one in which maturity is not merely undervalued but actively shunned.

No less striking to me, though, is the fact that Powell and Bogart are so present to us now, even though both men were born in the nineteenth century. Such, needless to say, is the curse of the movie camera: if you become a film star, you will always be remembered as you were, not as you are. Only the very greatest screen actors (I’m thinking of Jeff Bridges in Hell or High Water) are capable of accepting the inescapable reality of their advancing age and using it fearlessly and creatively.

My guess is that Bogart could have done so, but he died at fifty-seven, just too soon for us to know how he would have made the transition from leading man to character actor. As for Powell, he retired in 1955, presumably having concluded that he didn’t care to play second fiddle to younger, lesser men. Who shall blame him? Now he belongs to the ages, and the curse of the camera has become a blessing, for we can watch him in My Man Godfrey and come away feeling as though his scenes could have been shot yesterday.

Nobody feels that way about silent films. It was the introduction of sound that opened the door to the perpetual now of the movies, in which William Powell and Humphrey Bogart seem as real to us as Ben Affleck and Leonardo DiCaprio. Within a few short years of the release of The Jazz Singer, a handful of preternaturally gifted directors, Ernst Lubitsch and Jean Renoir foremost among them, had grappled successfully with the challenge of sound and were starting to make pictures like Trouble in Paradise and La Chienne that have the snap and immediacy to which the moviegoers of the Thirties quickly became accustomed, and in which I continue to take endless delight eight decades later.

Nobody feels that way about silent films. It was the introduction of sound that opened the door to the perpetual now of the movies, in which William Powell and Humphrey Bogart seem as real to us as Ben Affleck and Leonardo DiCaprio. Within a few short years of the release of The Jazz Singer, a handful of preternaturally gifted directors, Ernst Lubitsch and Jean Renoir foremost among them, had grappled successfully with the challenge of sound and were starting to make pictures like Trouble in Paradise and La Chienne that have the snap and immediacy to which the moviegoers of the Thirties quickly became accustomed, and in which I continue to take endless delight eight decades later.

It is more than likely that I will still be around when Trouble in Paradise turns 100, and perfectly possible that I will live to celebrate the centennial of My Man Godfrey. I wonder whether very many people will be watching these films, and others of like vintage, in 2036. I hope so, though I also wonder what they’ll make of William Powell. Will his maturity seem even more alien to them than it does to the youngsters of today? Or will the harshness of life in the twenty-first century by then have forced us all to stop crying for the moon? If so, at least we’ll have the great film comedies of the Thirties to remind us that even in the worst of times, it remains possible—nay, essential—to laugh.

* * *

A scene from My Man Godfrey, directed by Gregory La Cava and starring William Powell and Carole Lombard:

A scene from High Sierra, directed by Raoul Walsh and starring Humphrey Bogart, Ida Lupino, Alan Curtis, Arthur Kennedy, and Cornel Wilde: