“It is no good to think that other people are out to serve our interests.”

“It is no good to think that other people are out to serve our interests.”

Ivy Compton-Burnett, Elders and Betters

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City

My “Sightings” column for this week’s Wall Street Journal, which appeared on the paper’s website over the weekend, took note of the death on Friday of Edward Albee. It is running in today’s print editions. Here’s an excerpt.

* * *

Edward Albee, who died on Friday at the age of 88, wrote one of the half-dozen greatest American plays of the 20th century—and one of the half-dozen worst American plays of the past decade. In truth, far more of his 30-odd plays were bad than good. Most of the fulsome tributes to the author of “Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?” that have been posted, printed and tweeted since his death overlook this latter fact. Few of them, however, failed to mention that he couldn’t get a decent review between 1975 and 1994, when the off-Broadway production of “Three Tall Women” restored him to critical favor. If you didn’t know better, you might well suppose that the critics, not Mr. Albee himself, were mainly to blame for his long eclipse.

It’s easy to see why Mr. Albee metamorphosed from the bad boy of American theater into its grand old man. Not only did he live a long and productive life, but he was endlessly quotable and never hesitated to speak his mind, usually to hair-raising effect. But now that he is gone, it is his work, not his famously sharp tongue, for which he will be remembered—or not. “I have been overpraised and underpraised,” he said in 1982. “I assume by the time I finish writing—and I plan to go on writing until I’m 90 or gaga—it will all equal itself out.” But it hasn’t, not yet, and we are nowhere near sorting out his legacy. Was Albee a great playwright, or did he merely happen to write one great play?

It’s easy to see why Mr. Albee metamorphosed from the bad boy of American theater into its grand old man. Not only did he live a long and productive life, but he was endlessly quotable and never hesitated to speak his mind, usually to hair-raising effect. But now that he is gone, it is his work, not his famously sharp tongue, for which he will be remembered—or not. “I have been overpraised and underpraised,” he said in 1982. “I assume by the time I finish writing—and I plan to go on writing until I’m 90 or gaga—it will all equal itself out.” But it hasn’t, not yet, and we are nowhere near sorting out his legacy. Was Albee a great playwright, or did he merely happen to write one great play?

The greatness of “Virginia Woolf” certainly wasn’t evident to everyone at the time of its premiere. Robert Coleman of the New York Daily Mirror went so far as to call it “a sick play for sick people.” A fair number of other critics were equally disgusted by its snarling sexual frankness, as well as by Mr. Albee’s determination to stick a knife in the chest of what he took to be the complacent optimism of mid-century America. Like “The Rite of Spring” before it, “Virginia Woolf” was more a succès de scandale than an instantaneously clear-cut artistic triumph…

Three Broadway revivals and hundreds of regional stagings later, “Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?” is now universally regarded as a modern classic. But to this day, it remains the only one of Albee’s plays to have made a lasting impression on the general public, enough so that it was even spoofed on “The Simpsons.” And while “Three Tall Women,” “The Zoo Story” (1958), and “The Goat, or, Who Is Sylvia?” (2002) are also justly admired by critics and theatergoers and continue to be performed throughout America and the world, it would be an understatement to say that no such consensus exists as to the merits of the rest of his output….

* * *

Read the whole thing here.

An excerpt from Steppenwolf Theater Company’s 2011 Chicago revival of Edward Albee’s Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?, which transferred to the Arena Stage of Washington, D.C., and was produced on Broadway in 2012. It was directed by Pam MacKinnon and starred Carrie Coon, Madison Dirks, Tracy Letts, and Amy Morton:

As I was soaring through the skies of Pennsylvania the other day, my iPod served up Leopold Stokowski’s 1937 recording of Dukas’ The Sorcerer’s Apprentice (not currently available on CD, alas). You may know it as the piece to which Mickey Mouse nearly drowned in Fantasia. No sooner did it start playing than I broke out in a broad grin. The Sorcerer’s Apprentice always does that to me–and did so long before I ever saw Fantasia. It’s one of the many pieces of music that has the mysterious power to make me happy….

Read the whole thing here.

I recently read an article about the Washington production of Satchmo at the Waldorf that contained this observation:

I recently read an article about the Washington production of Satchmo at the Waldorf that contained this observation:

A soulful, nuanced snapshot of Louis “Satchmo” Armstrong’s late life beyond what any book-length biography could do alone, it’s biographical storytelling at its best and, as such, a justification for theater—as if we needed one. I had to wonder whether the impetus for the play had been an essential something the author’s earlier biography of Armstrong, and indeed the subject’s life, left unresolved.

Needless to say, I appreciated Alice B. Lloyd’s kind words, but what interested me more—and still does—was that second sentence. If I read her right, she wanted to know whether I wrote Satchmo at the Waldorf in order to do something that I couldn’t do in Pops: A Life of Louis Armstrong. That’s a provocative question, one for which I don’t have a simple answer.

I wrote Satchmo after a theatrical producer, John Schreiber, sent me an e-mail in December of 2009 suggesting that Pops could be turned into a play and asking whether I’d given any thought to trying my hand at the task. Until then I’d never given any thought to writing a play about Armstrong, or anyone else. Outside of a single abortive attempt at playwriting (it was awful) that predated my tenure as drama critic of The Wall Street Journal, I’d never tried to write for the stage until Paul Moravec and I started working on The Letter, our first opera, in the summer of 2006. Even after The Letter was successfully premiered by the Santa Fe Opera three years later, I still didn’t see myself as a potential playwright. The urge simply wasn’t there—not until Schreiber planted the seed.

That seed bore fruit very quickly: I wrote Satchmo two months later in a four-day-long frenzy of creativity. But at no time prior to or during those four days did I say to myself, If I were to write a play about Louis Armstrong, I could speculate about him in a way that wouldn’t have been appropriate in a biography.

That seed bore fruit very quickly: I wrote Satchmo two months later in a four-day-long frenzy of creativity. But at no time prior to or during those four days did I say to myself, If I were to write a play about Louis Armstrong, I could speculate about him in a way that wouldn’t have been appropriate in a biography.

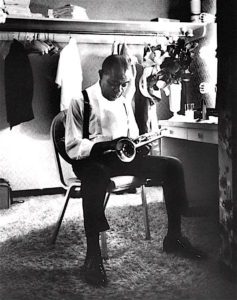

The actual inspiration for Satchmo was a photograph of Armstrong by Eddie Adams that was taken in his Las Vegas dressing room toward the end of 1970, nine months before his death. The photo, which is reproduced in Pops, shows Armstrong sitting in a chair before a performance, looking old, tired, and pensive. I’d known from the time I first saw the photo that I wanted to include it in Pops, in which I describe it as portraying “the moody, introspective man whom the public never saw.” Then as now, it reminded me of something that one of Armstrong’s sidemen once said about him:

“For all his popularity, Louis could be sitting in his dressing room and he looked like the saddest guy in the world,” Joe Darensbourg said. “That always amazed me. He’d be sitting with his horn in his hand, just looking at it, turning it over, looking at the bell, picking it up and blowing a little, that’s all.”

Two months after I first heard from John Schreiber, Adams’ photo popped back into my head. It’s the quintessential example of a picture that’s worth a thousand words, and as I thought of it, I suddenly saw in my mind’s eye the “stage picture” for the opening of Satchmo at the Waldorf. The first line of the play came to me a split-second later. (The opening of The Letter had come to me in the same way, and subsequent experience has taught me that this is how I get my ideas for plays and opera libretti.) I sat down and started writing a day or two after that, and by week’s end the first draft of Satchmo was finished.

Two months after I first heard from John Schreiber, Adams’ photo popped back into my head. It’s the quintessential example of a picture that’s worth a thousand words, and as I thought of it, I suddenly saw in my mind’s eye the “stage picture” for the opening of Satchmo at the Waldorf. The first line of the play came to me a split-second later. (The opening of The Letter had come to me in the same way, and subsequent experience has taught me that this is how I get my ideas for plays and opera libretti.) I sat down and started writing a day or two after that, and by week’s end the first draft of Satchmo was finished.

Once I got over the shock of having written a play, I started to think about what I’d done. It was only then that I realized that fictionalizing Armstrong’s life had made it possible for me to speculate about certain aspects of his complicated relationship with Joe Glaser, his longtime manager and the second of Satchmo’s three characters, in a way that went beyond what I could discuss with certainty in the pages of Pops. It also made it possible for me to dramatize my discovery that there were significant and fascinating differences between the public Armstrong and the private Armstrong. As I explained in a program note written two years after the fact, “Biography is about telling, theater about showing. Having written a book that told the story of Armstrong’s life, it occurred to me that it might be a worthwhile challenge to try to show an audience what he was like off stage.”

True enough—but that is, as I say, an oversimplification of what really happened. No doubt my subconscious was working along these lines in January and February of 2010, but if you’d asked me at the time why I wrote Satchmo, I probably would have said something not unlike what George Mallory famously said when asked by a reporter why he wanted to climb Mount Everest: “Because it’s there.” Never having given any serious thought to writing a play, I was thrilled by the brand-new challenge of doing so. Everything else was incidental.

Lest we forget, Mallory died on Mount Everest a year later, and nobody knows whether he reached the summit first. I, too, knew all too well that the chances of Satchmo’s ever being produced were minuscule to the point of nonexistence. Such miracles simply don’t happen to fifty-four-year-old novice playwrights—especially when they also happen to be drama critics. On the other hand, I knew enough about the business to recognize that Satchmo had a kind of abstract commercial potential, and that I might possibly get lucky if the breaks went my way.

Again, though, I didn’t write it for that reason. It was the pure challenge of writing a play that spurred me on, though it’s also true that I probably wouldn’t have tried writing Satchmo had John Schreiber been anything other than an experienced theatrical producer. (His two best-known shows are Jelly’s Last Jam and Elaine Stritch at Liberty.) I clearly remember thinking, Well, gee, this guy knows something about theater, right? If he thinks there’s a play in Pops, maybe I should give it a try.

Is there a moral to this story? Possibly, though it would be an understatement to say that I’m not into follow-your-bliss self-help gush. Just because I beat the odds with Satchmo doesn’t mean that you can, too. The cold, hard fact is that novice playwrights, like first-time novelists, scarcely ever have any luck at all. On the other hand, it’s also true, as the Powerball people like to say, that you can’t win if you don’t play. I have no doubt, though, that your best bet is to write purely for pleasure, with no expectation of success. We have it on the very best authority, after all, that you can’t make a living writing plays, and I wouldn’t dream of trying.

Is there a moral to this story? Possibly, though it would be an understatement to say that I’m not into follow-your-bliss self-help gush. Just because I beat the odds with Satchmo doesn’t mean that you can, too. The cold, hard fact is that novice playwrights, like first-time novelists, scarcely ever have any luck at all. On the other hand, it’s also true, as the Powerball people like to say, that you can’t win if you don’t play. I have no doubt, though, that your best bet is to write purely for pleasure, with no expectation of success. We have it on the very best authority, after all, that you can’t make a living writing plays, and I wouldn’t dream of trying.

All this said, let me circle back to where we started. No, I didn’t write Satchmo at the Waldorf in order to satisfy creative urges that were left unfilled by the writing of Pops, nor did I write it to make any kind of point about Louis Armstrong. I had only one motive in mind: to find out what would happen if I opened my laptop and typed ACT ONE. Now I know.

* * *

A trailer for the Mosaic Theater’s Washington production of Satchmo at the Waldorf, which has been extended through October 2:

To order tickets or for more information, go here.

Fayard and Harold Nicholas sing and dance “That Old Black Magic,” written by Harold Arlen and Johnny Mercer, on The Hollywood Palace. This episode was originally telecast by ABC on February 27, 1965:

Fayard and Harold Nicholas sing and dance “That Old Black Magic,” written by Harold Arlen and Johnny Mercer, on The Hollywood Palace. This episode was originally telecast by ABC on February 27, 1965:

(This is the latest in a series of arts-related videos that appear in this space each Monday, Wednesday, and Friday)

An ArtsJournal Blog