In today’s Wall Street Journal “Sightings” column, I discuss the published version of Harry Potter and the Cursed Child and the problem of reading a play you haven’t seen. Here’s an excerpt.

* * *

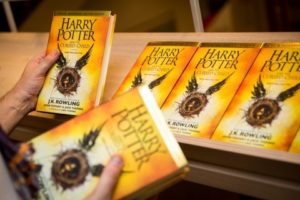

What does it mean to call a book a “best seller”? According to Publisher’s Weekly, you have to sell 328 copies a day to crack Amazon’s top-five fiction list. So consider this: “Harry Potter and the Cursed Child” was published on July 31. By Aug. 2, it had sold two million copies.

So far, most of those two million readers appear to be perfectly happy with the new Harry Potter book. But the reviews posted on Amazon suggest that a fair number of them are sorely disappointed. Nearly a quarter of the reviewers gave the book a rock-bottom one-star rating. Some were vexed because J.K. Rowling didn’t write it, a fact that is noted on the cover, though you have to look twice to see it. In addition, though, many people seem to have been surprised to learn that “Harry Potter and the Cursed Child” is not a novel by Ms. Rowling but a play by Jack Thorne. (For the record, it opened in London two weeks ago to rave reviews.)

Meaning what? Well, here’s how “HPATCC” starts out: “ACT ONE, SCENE ONE. KING’S CROSS. A busy and crowded station. Full of people trying to go somewhere. Amongst the hustle and bustle, two large cages rattle on top of two laden trolleys. They’re being pushed by two boys, JAMES POTTER and ALBUS POTTER, their mother, GINNY, follows after. A 37-year-old man, HARRY, has his daughter, LILY, on his shoulders.” At that point, the characters start talking and the play gets under way.

Meaning what? Well, here’s how “HPATCC” starts out: “ACT ONE, SCENE ONE. KING’S CROSS. A busy and crowded station. Full of people trying to go somewhere. Amongst the hustle and bustle, two large cages rattle on top of two laden trolleys. They’re being pushed by two boys, JAMES POTTER and ALBUS POTTER, their mother, GINNY, follows after. A 37-year-old man, HARRY, has his daughter, LILY, on his shoulders.” At that point, the characters start talking and the play gets under way.

Compare this with the opening of “Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone,” the first Potter novel: “Mr. and Mrs. Dursley, of number four, Privet Drive, were proud to say that they were perfectly normal, thank you very much. They were the last people you’d expect to be involved in anything strange or mysterious, because they just didn’t hold with such nonsense.” This is followed by three full pages of richly detailed description. Only then do the characters start talking.

Therein lies the problem: Unlike a novel, the script of a play is a set of instructions for creating a theatrical experience, not the experience itself. If you read a script after you’ve seen the play, you’ll remember what you saw, and the action will make sense to you. If not, you’ll have to “stage” the play for yourself in your mind’s eye. Unless you’re a theatrical professional or a seasoned playgoer, you’re likely to find that difficult to do….

* * *

Read the whole thing here.

•

•