In today’s Wall Street Journal “Sightings” column, I report and reflect on an exhibition of the “serious” paintings of N.C. Wyeth. Here’s an excerpt.

* * *

I can’t remember the last time I heard a screenwriter, a mystery novelist or a show-tune composer express regret for having embraced so “lowly” a calling. Nowadays, popular artists know that what they do is valuable in its own right. It hardly seems possible that when Aaron Copland went to Hollywood in 1939 to score Lewis Milestone’s film version of John Steinbeck’s “Of Mice and Men,” many of his fellow highbrows were sure that he was finished as a classical composer. Today, they’d ask him for a letter of recommendation.

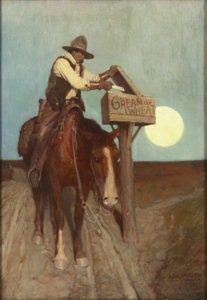

I thought of Copland’s film scores when I went to see “N.C. Wyeth: Painter,” an exhibition on display through December 31 at the Farnsworth Art Museum in Rockland, Maine. Wyeth, who died in 1945, was the father of Andrew Wyeth, perhaps the most famous and beloved American painter of the 20th century. In his lifetime, though, N.C. was equally famous—though not as a maker of what we stubbornly continue to call “fine art.” He was, rather, the most highly paid commercial illustrator of his day. While Wyeth is now mainly known for having illustrated such children’s classics as “Robinson Crusoe,” “Treasure Island” and “The Yearling,” his work also appeared on the covers of mass-circulation magazines like Ladies’ Home Journal and the Saturday Evening Post, and in ads for Cream of Wheat and Lucky Strike cigarettes….

I thought of Copland’s film scores when I went to see “N.C. Wyeth: Painter,” an exhibition on display through December 31 at the Farnsworth Art Museum in Rockland, Maine. Wyeth, who died in 1945, was the father of Andrew Wyeth, perhaps the most famous and beloved American painter of the 20th century. In his lifetime, though, N.C. was equally famous—though not as a maker of what we stubbornly continue to call “fine art.” He was, rather, the most highly paid commercial illustrator of his day. While Wyeth is now mainly known for having illustrated such children’s classics as “Robinson Crusoe,” “Treasure Island” and “The Yearling,” his work also appeared on the covers of mass-circulation magazines like Ladies’ Home Journal and the Saturday Evening Post, and in ads for Cream of Wheat and Lucky Strike cigarettes….

But Wyeth believed that he was squandering his great gifts. Unable to regard illustration as anything more than “the art of journalism, to be rendered in the manner of painting,” he dreamed of being praised as “a painter who has shaken the dust of the illustrator from his heels!!” So he spent his spare time working on landscapes, portraits and studies of life in coastal Maine, where he spent his summers. He saw these paintings, which bear such homely titles as “The Harbor Herring Gut” and “Fisherman’s Family,” as “the beginning of more important self-expression,” and they were intended not for magazines but galleries—and, eventually, museums….

Art critics and historians haven’t had much to say about Wyeth’s “serious” work. David Michaelis, author of “N.C. Wyeth,” an excellent 1998 biography which argues that his illustrations deserve to be taken very seriously indeed—a point of view now generally accepted by scholars—wrote off Wyeth’s “independent” paintings in a single curt sentence: “He deliberately intended these paintings to be taken as statements of his most personal feelings, yet he left out or deflated the very pictorial elements that made his canvases most his own.”

Art critics and historians haven’t had much to say about Wyeth’s “serious” work. David Michaelis, author of “N.C. Wyeth,” an excellent 1998 biography which argues that his illustrations deserve to be taken very seriously indeed—a point of view now generally accepted by scholars—wrote off Wyeth’s “independent” paintings in a single curt sentence: “He deliberately intended these paintings to be taken as statements of his most personal feelings, yet he left out or deflated the very pictorial elements that made his canvases most his own.”

To visit the Farnsworth, however, is to realize that Mr. Michaelis got it almost exactly wrong. These burgeoningly vital, at times near-primitive paintings, whose bold swashes of magenta and turquoise recall the Fauvism of André Derain and Henri Matisse, make Andrew look prim….

* * *

Read the whole thing here.