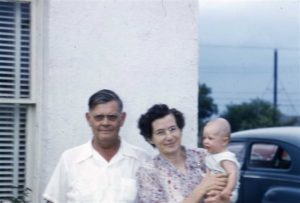

My mother’s parents were born right around the turn of the twentieth century. Albert Crosno, Sr., my maternal grandfather, came from Decaturville, a rural Tennessee town whose current population is 867, and spent the bulk of his later life in Diehlstadt, a rural Missouri town whose current population is 161. He served as a private in World War I, became a dirt farmer after the war, then went to work in a shoe factory. After hours he played the banjo, listened to the Grand Ole Opry on the radio, and doted on his two sons and four daughters.

My mother’s parents were born right around the turn of the twentieth century. Albert Crosno, Sr., my maternal grandfather, came from Decaturville, a rural Tennessee town whose current population is 867, and spent the bulk of his later life in Diehlstadt, a rural Missouri town whose current population is 161. He served as a private in World War I, became a dirt farmer after the war, then went to work in a shoe factory. After hours he played the banjo, listened to the Grand Ole Opry on the radio, and doted on his two sons and four daughters.

I have only the vaguest memories of Albert, who died of a heart attack when I was six years old, but Gracie, his wife, lived well into my adulthood. Alas, she spent her last years in a cloud of senility, making it impossible for me to get to know her more than superficially, though I clearly remember her devotion to the soap operas that she watched on TV every afternoon, which she called “my stories,” and her keep-my-skillet-good-and-greasy country cooking. Whenever I read about pioneer women, I see in my mind’s eye Gracie sweating over a hot stove while Albert sat in his rocking chair, frailing away at his banjo.

I’ve been thinking about my grandparents ever since I started reading Hillbilly Elegy, a memoir by J.D. Vance, who grew up in Middletown, Ohio, joined the Marines, attended Yale Law School, and now works in Silicon Valley. It tells the story of how the members of his family, who moved to Ohio from Breathitt County, Kentucky, in the hope of escaping the grinding Appalachian poverty into which they were born, were permanently scarred by the world they left behind, the same world that Gracie and Albert had left behind them three-quarters of a century earlier.

I’ve been thinking about my grandparents ever since I started reading Hillbilly Elegy, a memoir by J.D. Vance, who grew up in Middletown, Ohio, joined the Marines, attended Yale Law School, and now works in Silicon Valley. It tells the story of how the members of his family, who moved to Ohio from Breathitt County, Kentucky, in the hope of escaping the grinding Appalachian poverty into which they were born, were permanently scarred by the world they left behind, the same world that Gracie and Albert had left behind them three-quarters of a century earlier.

If you watched Justified, you have some sense of what that world is like today. If not, Vance talked about it in detail in a recent interview with Rod Dreher that is both frank and illuminating:

What many don’t understand is how truly desperate these places are, and we’re not talking about small enclaves or a few towns–we’re talking about multiple states where a significant chunk of the white working class struggles to get by. Heroin addiction is rampant. In my medium-sized Ohio county last year, deaths from drug addiction outnumbered deaths from natural causes. The average kid will live in multiple homes over the course of her life, experience a constant cycle of growing close to a “stepdad” only to see him walk out on the family, know multiple drug users personally, maybe live in a foster home for a bit (or at least in the home of an unofficial foster like an aunt or grandparent), watch friends and family get arrested, and on and on. And on top of that is the economic struggle, from the factories shuttering their doors to the Main Streets with nothing but cash-for-gold stores and pawn shops.

The book itself is, if anything, scarier:

Our homes are a chaotic mess. We scream and yell at each other like we’re spectators at a football game. At least one member of the family uses drugs…At especially stressful times, we’ll hit and punch each other, all in front of the rest of the family, including young children; much of the time, the neighbors hear what’s happening. A bad day is when the neighbors call the police to stop the drama. Our kids go to foster care but never stay for long. We apologize to our kids. The kids believe we’re really sorry, and we are. But then we act just as mean a few days later.

I suppose you could have called Gracie and Albert “hillbillies,” but you would have been stretching a point to do so. Nor did they have much in common with the latter-day hillbillies portrayed in Vance’s book. They were good country people, Scotch-Irish Bible Belt Christians (my mother was baptized in a river) who scratched their way through the Great Depression and World War II, passing on their homespun, hard-tested values to their children, who in turn raised their own children in much the same way. What I am, I owe to them. As I wrote in this space last summer, “To come from such unfancy people, ordinary though they may be by the standards of the gilded city in which I now live, is to have a leg up in the long race of life, all the way from the starting gun to the finish line.”

I suppose you could have called Gracie and Albert “hillbillies,” but you would have been stretching a point to do so. Nor did they have much in common with the latter-day hillbillies portrayed in Vance’s book. They were good country people, Scotch-Irish Bible Belt Christians (my mother was baptized in a river) who scratched their way through the Great Depression and World War II, passing on their homespun, hard-tested values to their children, who in turn raised their own children in much the same way. What I am, I owe to them. As I wrote in this space last summer, “To come from such unfancy people, ordinary though they may be by the standards of the gilded city in which I now live, is to have a leg up in the long race of life, all the way from the starting gun to the finish line.”

What happened to the full-fledged hillbillies my grandparents left behind in Appalachia? Why did their great-grandchildren exchange their unselfconscious faith for self-ravaging hopelessness? I leave it to others to plumb the moral disintegration of America’s rural working class, for I know nothing of it at first hand. The small Missouri town in which I grew up, though far from wealthy, was nothing like Breathitt County, Kentucky. All I know is that Gracie and Albert lived at a time when the behavior chronicled in Hillbilly Elegy was, quite literally, unthinkable. I weep to imagine what they would have thought of it.

* * *

Uncle Dave Macon sings “Take Me Back to That Old Carolina Home,” accompanied by his son Dorris. This clip, an excerpt from the 1940 film Grand Ole Opry, is thought to be the only surviving sound film of Macon in performance: