In a popular culture, fame is cheap. That’s what Andy Warhol meant when he said that in the future, everybody would be famous for fifteen minutes. (Remember JenniCam?) It’s also what I had in mind—part of it, anyway—when I wrote these words eleven years ago:

Television can make you famous, but it can’t keep you famous. It’s more like an opiate—as soon as you stop taking your daily fix, you get all pale and clammy, and before long you vanish in a puff of near-transparent smoke. So far as I know, there’s never been a TV star, no matter how big, who stayed famous for very long once he or she went off the air.

I was talking about Harry Reasoner, but you don’t have to be, or have been, a TV star to know how fast stardom fades. I wonder whether Warhol ever thought about that: what happens when your fifteen minutes are up? Even more interesting, what happens when you outlive your fifteen minutes by…oh, fifty years?

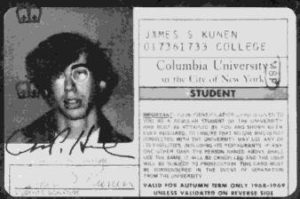

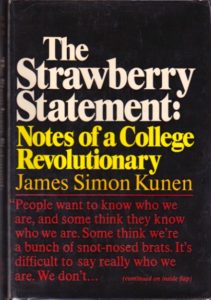

What put these questions in my mind was the fate of James Simon Kunen, a celebrity of my youth whose name popped into my mind the other day for no particular reason. In 1969 he wrote a book called The Strawberry Statement: Notes of a College Revolutionary in which he described his involvement in the Columbia University protests of 1968. I read Kunen’s book when I was in high school and found it smart and funny, a critical judgment that I rather doubt I would be equally inclined to render were I to re-read it today, judging by the following passage:

What put these questions in my mind was the fate of James Simon Kunen, a celebrity of my youth whose name popped into my mind the other day for no particular reason. In 1969 he wrote a book called The Strawberry Statement: Notes of a College Revolutionary in which he described his involvement in the Columbia University protests of 1968. I read Kunen’s book when I was in high school and found it smart and funny, a critical judgment that I rather doubt I would be equally inclined to render were I to re-read it today, judging by the following passage:

I, for one, strongly support trees (and, in the larger sense, forests), flowers, mountains, and hills, also valleys, the ocean, wiliness (when used for good), good, little children, people, tremendous record-setting snowstorms, hurricanes, swimming underwater, nice policemen, unicorns, extra-inning ball games up to twelve innings, pneumatic jack-hammers (when they’re not too close), the dunes in North Truro on Cape Cod, liberalized abortion laws, and Raggedy Ann dolls, among other things.

I do not like Texas, people who go to the Zoo to be arty. the Defense Department, the name “Defense Department,” the fly buzzing around me as I write this, protective tariffs, little snowstorms that turn to slush, the short days of winter, extra-inning ball games over twelve innings, calling people consumers, pneumatic jackhammers immediately next to the window, and G.I. Joe dolls. Also racism, poverty, and war. The latter three I’m trying to do something about.

Nevertheless, The Strawberry Statement made its author famous—briefly. In 1970 it was turned into a movie that sank without trace. Kunen then became a journalist, got a law degree, and worked as a public defender in Washington, D.C. He kept on writing books, but none of them drew much attention. His fifteen minutes were up. So he joined the staff of People and spent the next two decades in the employ of Time Inc., a development that I find especially poignant. Rightly or wrongly, I have a sneaking feeling that Jeff Goldblum’s character in The Big Chill, an erstwhile campus radical who now works for a People-like magazine, might possibly have been based on Kunen: “Where I work we only have one editorial rule. You can’t write anything longer than it takes your average person to take an average crap.”

Nevertheless, The Strawberry Statement made its author famous—briefly. In 1970 it was turned into a movie that sank without trace. Kunen then became a journalist, got a law degree, and worked as a public defender in Washington, D.C. He kept on writing books, but none of them drew much attention. His fifteen minutes were up. So he joined the staff of People and spent the next two decades in the employ of Time Inc., a development that I find especially poignant. Rightly or wrongly, I have a sneaking feeling that Jeff Goldblum’s character in The Big Chill, an erstwhile campus radical who now works for a People-like magazine, might possibly have been based on Kunen: “Where I work we only have one editorial rule. You can’t write anything longer than it takes your average person to take an average crap.”

And what happened to him in the end? Curious, I took to Google, and within a minute or two I was reading a story called “Older Job Seekers Find Ways to Avoid Age Bias” that was published last year in the New York Times as part of a weekly series called “Retiring.” The story makes no mention of The Strawberry Statement, or of Kunen’s youthful notoriety:

James S. Kunen, 66, teaches English as a second language at the Center for Immigrant Education and Training at LaGuardia Community College in Queens.

When he was let go as the director of corporate communications at Time Warner during a round of layoffs, Mr. Kunen confronted the core questions: What is it he could do? Where did his skills translate to a job, one that made him feel some sense of purpose? And who would hire him, given his age?…

Before he was laid off, Mr. Kunen volunteered to teach immigrant teenagers to speak better English, but concluded that if he was going to do it right, and get paid for it, he needed some kind of certification. So he enrolled in a 160-hour course to earn a certificate to teach English as a Second Language for Adults.

“When I initially sent out résumés to commercial language schools, the only school that responded was one run by a person as old as I was,” said Mr. Kunen, the author of “Diary of a Company Man: Losing a Job, Finding a Life.” “And I was interviewed by 30-year-olds who totally didn’t ‘get’ me,” he said. “You can sense it immediately; it’s like being on a bad blind date.”

For Mr. Kunen, patience and persistence paid off. Today, he spends 16 hours a week in the classroom teaching two courses. “At this age and stage of my life, working with highly motivated immigrants gives me a sense of purpose and engagement with the world,” he said. “Going to work is spending time with friends. I feel appreciated.”

The linchpin: “It also gives me an income that makes a significant difference when added to my pension and Social Security.”…

I’m tempted to read Diary of a Company Man, but I have a feeling that I might find it too sad to bear, seeing as how I’m just eight years younger than Kunen. Ours, after all, was the generation that expected to live by the words of Pete Townshend: I hope I die before I get old. But Townshend didn’t, nor did James Simon Kunen, who now ekes out his pension and Social Security by teaching English to immigrant teenagers.

I’m tempted to read Diary of a Company Man, but I have a feeling that I might find it too sad to bear, seeing as how I’m just eight years younger than Kunen. Ours, after all, was the generation that expected to live by the words of Pete Townshend: I hope I die before I get old. But Townshend didn’t, nor did James Simon Kunen, who now ekes out his pension and Social Security by teaching English to immigrant teenagers.

To be sure, I was, unlike Kunen, spared the dubious privilege of youthful fame (or any kind of fame, truth to tell). What’s more, I recently embarked on a professional adventure of a sort that sexagenarians are rarely lucky enough to experience. Nevertheless, I think I have at least some notion of how it might possibly feel to outlive your life as you’d previously understood it, and the fact that Kunen now seems by all accounts to be genuinely happy—which is, lest we forget, the most important thing about him—doesn’t make me feel any more at ease as I look down the road toward my own unknowable future.

A.E. Housman said it:

Now you will not swell the rout

Of lads that wore their honours out,

Runners whom renown outran

And the name died before the man.

I wonder what Andy Warhol thought of those lines—if he knew them. On the other hand, he died at the age of fifty-eight, thereby ensuring that we would always remember him (if, indeed, we do continue to remember him) as young, decadent, and way, way cool. Smart move, that.

* * *

The trailer for the film version of The Strawberry Statement: