Twitter, like the world itself, is populated partly by thoughtful, open-minded people and partly by knee-jerking robots of flesh and blood who are incapable of reacting other than automatically and reflexively to the external stimuli of life. Mention anything bad that Donald Trump just did and within seconds you’ll be pelted by tweets hastening to assure you that Hillary Clinton does the very same thing, only (A) more often and (B) much worse.

It works both ways, of course. Most things do—which is my point. I tweeted the other day that if I owned a time machine, I’d set it to 1959, and a minute or so later I heard from a stranger who was under the mistaken impression that I needed to be reminded that things weren’t so hot for blacks and women back then. Shame on me, in other words, for daring to suppose that America in 1959—the year in which, among other noteworthy things, Miles Davis recorded Kind of Blue and Lorraine Hansberry’s A Raisin in the Sun opened on Broadway—was something other than a stinking cesspool of pure, unmitigated hate.

It works both ways, of course. Most things do—which is my point. I tweeted the other day that if I owned a time machine, I’d set it to 1959, and a minute or so later I heard from a stranger who was under the mistaken impression that I needed to be reminded that things weren’t so hot for blacks and women back then. Shame on me, in other words, for daring to suppose that America in 1959—the year in which, among other noteworthy things, Miles Davis recorded Kind of Blue and Lorraine Hansberry’s A Raisin in the Sun opened on Broadway—was something other than a stinking cesspool of pure, unmitigated hate.

I rarely reply to such self-righteous folk, there being no point in it. Arguing with a robot, be he or she of the right or left, is like arguing with a drunk. Once in a while, though, somebody tweets something so shatteringly obtuse that I find it impossible to keep my big mouth shut. Only yesterday, for example, I was engaged in a three-way “conversation” about Bill Dana, a once-popular standup comedian of the Sixties whose act consisted in large part of an impersonation of a slow-witted Bolivian by the name of José Jiménez. I hadn’t thought of him for years when a friend of mine tweeted, apropos of Donald Trump’s attacks on Judge Gonzalo Curiel, that he’d recently heard an old José Jiménez routine on Sirius XM. “Not only wasn’t it funny, it really was appallingly racist,” he said. (My friend, for the record, happens to be a very well-known neoconservative.)

This surprised me, for I had vivid childhood memories of enjoying Dana’s TV appearances, though the only specific thing I could remember about them was his invariable opening line, “My name…José Jiménez,” which he delivered in a foot-thick south-of-the-border accent. Since Dana was a regular on variety shows well into the Seventies, I figured I wouldn’t have any trouble tracking down one of his routines on YouTube, so I went there and spent a few minutes refreshing my memory. I, too, was startled by the unthinking racism of Dana’s old-fashioned style of comedy, and said so in my reply. “Kind of amazing how it makes Amos & Andy seem sort of mild by comparison,” another follower added.

This surprised me, for I had vivid childhood memories of enjoying Dana’s TV appearances, though the only specific thing I could remember about them was his invariable opening line, “My name…José Jiménez,” which he delivered in a foot-thick south-of-the-border accent. Since Dana was a regular on variety shows well into the Seventies, I figured I wouldn’t have any trouble tracking down one of his routines on YouTube, so I went there and spent a few minutes refreshing my memory. I, too, was startled by the unthinking racism of Dana’s old-fashioned style of comedy, and said so in my reply. “Kind of amazing how it makes Amos & Andy seem sort of mild by comparison,” another follower added.

A stranger then muscled into what up to that moment had been a perfectly peaceable chat, belligerently pointing out that we were talking about a fifty-year-old comedy routine and that I needed to “lighten up.” “Do you find it funny and charming now?” I responded. “Because that’s what we’re talking about. Hell, I thought it was funny fifty years ago—but I was ten years old, and that was fifty years ago.” The stranger promptly tweeted back something boorish in response. “Fuck off,” I replied, then blocked him. (I’m no longer civil to uncivil people on Twitter.) That little exchange attracted the attention of yet another bonehead, who tweeted as follows: “An Hispanic doing an exaggerated Hispanic accent is racist? Hillary has affected accent when in black church.” Recognizing a robot when I saw one, I limited myself this time to pointing out that Dana, far from being Hispanic, was of Hungarian-Jewish descent. Answer, not surprisingly, came there none, and the conversation drifted off in other directions, as Twitter chats are wont to do.

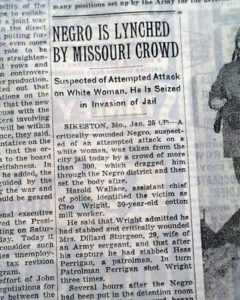

Which brings us right back to where we started. Those who think that human life is anything other than a fearfully complicated and ambiguous affair are kidding themselves. If you’re a regular reader of this blog, you know that I have powerful feelings of nostalgia and love for the simpler, quieter world of my small-town childhood—but you also know that the last American lynching to take place outside the Deep South occurred in my home town in 1942, and that I happen to be just old enough to clearly remember seeing, and using, separate entrances for “white” and “colored.” I need no “schooling” about such horrors. Unlike my self-appointed schoolmasters, I saw them for myself.

Which brings us right back to where we started. Those who think that human life is anything other than a fearfully complicated and ambiguous affair are kidding themselves. If you’re a regular reader of this blog, you know that I have powerful feelings of nostalgia and love for the simpler, quieter world of my small-town childhood—but you also know that the last American lynching to take place outside the Deep South occurred in my home town in 1942, and that I happen to be just old enough to clearly remember seeing, and using, separate entrances for “white” and “colored.” I need no “schooling” about such horrors. Unlike my self-appointed schoolmasters, I saw them for myself.

Alas, I increasingly incline to suspect that many, perhaps most people don’t think at all. Instead they react, almost always in the most predictable way possible, and every “opinion” they have fits together neatly—and tiresomely. Such folk take it for granted that I must be evil or unenlightened (to them, there’s no difference) because I persist in believing that America in 1959 was neither all good nor all bad. Or because I take the dimmest possible view of the social-justice warriors who are currently engaging in such lunatic and dangerous antics as this. Or, for that matter, because I no longer find José Jiménez funny.

Isaiah Berlin said it:

You must believe me, one cannot have everything one wants—not only in practice, but even in theory. The denial of this, the search for a single, overarching ideal because it is the one and only true one for humanity, invariably leads to coercion. And then to destruction, blood—eggs are broken, but the omelette is not in sight, there is only an infinite number of eggs, human lives, ready for the breaking. And in the end the passionate idealists forget the omelette, and just go on breaking eggs.

And if you think otherwise? Then my considered reply to you is: fuck off.

* * *

Bill Dana in an undated kinescope of one of his TV appearances from the Sixties:

A scene from the 1959 film version of Lorraine Hansberry’s A Raisin in the Sun, starring Sidney Poitier: