Louis Armstrong and His All Stars perform “A Kiss to Build a Dream On” in concert in 1962:

Louis Armstrong and His All Stars perform “A Kiss to Build a Dream On” in concert in 1962:

(This is the latest in a series of arts-related videos that appear in this space each Monday, Wednesday, and Friday)

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City

Over the weekend I spent two consecutive twelve-hour working days in technical rehearsals for my Palm Beach Dramaworks production of Satchmo at the Waldorf. I say “my” because I wrote the play and am directing it, but nothing drives home the collaborative nature of theater quite like tech, in which the director, design team, and stage crew of a show work hand in hand to build, polish, and rehearse the lighting and sound cues that transform what happened in the rehearsal hall to what will happen in front of an audience.

Over the weekend I spent two consecutive twelve-hour working days in technical rehearsals for my Palm Beach Dramaworks production of Satchmo at the Waldorf. I say “my” because I wrote the play and am directing it, but nothing drives home the collaborative nature of theater quite like tech, in which the director, design team, and stage crew of a show work hand in hand to build, polish, and rehearse the lighting and sound cues that transform what happened in the rehearsal hall to what will happen in front of an audience.

Tech is a grueling, painstaking, time-consuming process that requires infinite patience. If you’re a naturally impatient person—as I am, I regret to say—it can be tedious in the extreme. But if—as I also am—you’re the kind of person who has a taste for taking infinite pains, then it can be one of the most engrossing and pleasurable experiences that theater has to offer. It’s the Orson Welles part of stage directing: you get to pull out the toy box and spend hours and hours playing with it. You fuss endlessly and productively over every single lighting cue, making one part of the stage dark and another bright, with the lighting designer saying “Do you like it better this way, or this way?” over and over again like a demented ophthalmologist.

I tweeted about our tech rehearsals as they were in progress, and a jazz-singing friend of mine who has also worked in theater responded as follows:

I tweeted about our tech rehearsals as they were in progress, and a jazz-singing friend of mine who has also worked in theater responded as follows:

Tech has always been my favorite part of the rehearsal process. Such a joy and relief to incorporate lights, sound, and costumes after you’ve been stuck in a rehearsal room pretending they’re there. It’s when the production becomes real, and you get to work through all the magical technical moments.

My—our—production of Satchmo is full of such moments, a few of which are sufficiently surprising that I don’t want to give them away. Most, though, are intended to be so subtle as to escape the conscious notice of the audience. Their purpose is to heighten the atmosphere of the show without drawing attention to themselves, and to make you concentrate all the more closely on the action and actors.

In the case of Satchmo, we have only one actor, Barry Shabaka Henley, who did the show earlier this year in Chicago in a completely different-looking production. I’ve found it inspiring to watch Shabaka adjust with seeming effortlessness to this new setting, and to see his interpretation of the triple role of Louis Armstrong, Joe Glaser, and Miles Davis grow richer and more complex with each passing day. Like John Douglas Thompson and Dennis Neal before him, he is a true artist, and I am lucky beyond words to have him doing the show.

That said, tech is less about the actor than about the people you don’t see on stage, and I couldn’t begin to say enough about them. Mike Amico, his wife Erin, Kirk Bookman, and Matt Corey, designed the set, costumes, lighting, and sound for Satchmo, and they are, each and every one, masters of their crafts. So are James Danford and Ashley Horowitz, the stage manager and assistant manager, who (if I may mix my metaphors) keep the balls in the air and make the trains run on time. Between them, they’ve all helped to turn the production in my head into a living, breathing thing, and it is no false modesty but the simple truth when I say that I couldn’t have even begun to do it without them.

That said, tech is less about the actor than about the people you don’t see on stage, and I couldn’t begin to say enough about them. Mike Amico, his wife Erin, Kirk Bookman, and Matt Corey, designed the set, costumes, lighting, and sound for Satchmo, and they are, each and every one, masters of their crafts. So are James Danford and Ashley Horowitz, the stage manager and assistant manager, who (if I may mix my metaphors) keep the balls in the air and make the trains run on time. Between them, they’ve all helped to turn the production in my head into a living, breathing thing, and it is no false modesty but the simple truth when I say that I couldn’t have even begun to do it without them.

All of which brings us to the eve of the moment of truth. Tonight is the final dress rehearsal. The first public preview of Satchmo at the Waldorf is Wednesday, with a second preview the next day. We—we—open on Friday. So far, so good. As of this morning, those are the eight happiest words I know.

On Monday morning I pulled on my sweats, hailed a cab, and made my way across town to the office of my cardiologist, unfed and insufficiently slept but on the whole optimistic. A few minutes after arriving I was whisked into an examination room, where a technician threaded an intravenous needle into my right arm and pumped me full of thallium. “You’re going to be radioactive for the next couple of days,” she told me matter-of-factly. “Let us know if you’re going to be traveling by air or if you have to enter a federal building–any place with metal detectors–and we’ll give you a card so that they’ll know why you’re setting off the machine.” Then she escorted me to another room containing a large, ominous-looking machine upon which I reclined motionless while a second technician took pictures of my heart….

Read the whole thing here.

“We shed as we pick up, like travellers who must carry everything in their arms, and what we let fall will be picked up by those behind. The procession is very long and life is very short. We die on the march. But there is nothing outside the march so nothing can be lost to it. The missing plays of Sophocles will turn up piece by piece, or be written again in another language. Ancient cures for diseases will reveal themselves once more. Mathematical discoveries glimpsed and lost to view will have their time again. You do not suppose, my lady, that if all of Archimedes had been hiding in the great library of Alexandria, we would be at a loss for a corkscrew?”

“We shed as we pick up, like travellers who must carry everything in their arms, and what we let fall will be picked up by those behind. The procession is very long and life is very short. We die on the march. But there is nothing outside the march so nothing can be lost to it. The missing plays of Sophocles will turn up piece by piece, or be written again in another language. Ancient cures for diseases will reveal themselves once more. Mathematical discoveries glimpsed and lost to view will have their time again. You do not suppose, my lady, that if all of Archimedes had been hiding in the great library of Alexandria, we would be at a loss for a corkscrew?”

Tom Stoppard, Arcadia

In today’s Wall Street Journal I file the first of two reports from Baltimore’s Everyman Theatre, which is currently presenting Death of a Salesman and A Streetcar Named Desire in rotating repertory. Here’s an excerpt.

In today’s Wall Street Journal I file the first of two reports from Baltimore’s Everyman Theatre, which is currently presenting Death of a Salesman and A Streetcar Named Desire in rotating repertory. Here’s an excerpt.

* * *

Old-fashioned repertory theater, in which a resident ensemble of actors performs a varied group of plays that are mounted in regular rotation, is so much a thing of the past that unless you frequent summer festivals—or major opera houses—you’re not likely ever to have seen it in action. It costs too much for most regional companies even to consider maintaining a permanent or semi-permanent resident acting ensemble, and without the existence of such an ensemble, rotating repertory is impractical to the point of impossibility. Instead we typically get productions in which actors and designers are thrown together on an ad-hoc basis to do shows that run for a month or so, after which a brand-new team of artists is assembled to rehearse and perform a brand-new show.

It goes without saying that such productions can be distinguished—that’s how Broadway works—but it’s also true that the aesthetic unanimity of an ensemble whose members know one another’s styles and minds can immeasurably enhance a show’s total effect. So Baltimore’s Everyman Theatre is doing something very much out of the ordinary by performing Arthur Miller’s “Death of a Salesman” and Tennessee Williams’ “A Streetcar Named Desire,” the two most popular and influential American plays of the ’40s, in rotating repertory….

It makes perfect sense to do “Salesman” and “Streetcar” in this way, not least because the two plays, for all their obvious differences, have much in common: Both are dramas of domestic discontent, part naturalistic and part poetic, that opened on Broadway in groundbreaking productions that were directed by Elia Kazan, designed by Jo Mielziner and accompanied by the incidental music of Alex North. Yet Everyman is, so far as anyone seems to know, the first company in the world ever to present them in rotating repertory, and having recently seen both productions in close succession, I can assure you that to do so is a powerfully stirring experience, one that will stick with you for a long time to come….

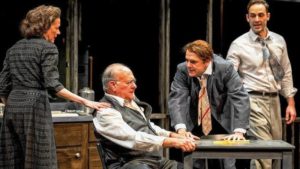

Since “Death of a Salesman” opened first, I’ll put off discussing “Streetcar” until next week and concentrate instead on the considerable virtues of Vincent M. Lancisi’s “Salesman” staging, which is traditional in the best possible way. Mr. Lancisi has steered clear of the high-concept road favored by Ivo van Hove in his recent Broadway revivals of “The Crucible” and “A View from the Bridge.” His “Salesman” is Miller’s “Salesman,” played out with absolute and admirable transparency on a skeletal two-story set designed by Daniel Ettinger that is unmistakably reminiscent (though not slavishly so) of the original Broadway production. The scale of the acting is as modest as that of Everyman’s 250-seat auditorium: Wil Love, who plays Willy Loman, appears to be the shortest man in the cast, and his performance, by turns querulous and ingratiating, is the living embodiment of one of Willy’s most striking lines, “I still feel—kind of temporary about myself.”…

Since “Death of a Salesman” opened first, I’ll put off discussing “Streetcar” until next week and concentrate instead on the considerable virtues of Vincent M. Lancisi’s “Salesman” staging, which is traditional in the best possible way. Mr. Lancisi has steered clear of the high-concept road favored by Ivo van Hove in his recent Broadway revivals of “The Crucible” and “A View from the Bridge.” His “Salesman” is Miller’s “Salesman,” played out with absolute and admirable transparency on a skeletal two-story set designed by Daniel Ettinger that is unmistakably reminiscent (though not slavishly so) of the original Broadway production. The scale of the acting is as modest as that of Everyman’s 250-seat auditorium: Wil Love, who plays Willy Loman, appears to be the shortest man in the cast, and his performance, by turns querulous and ingratiating, is the living embodiment of one of Willy’s most striking lines, “I still feel—kind of temporary about myself.”…

The signal advantage of this approach is that it offsets the fundamental flaw of “Salesman,” which is Miller’s lifelong weakness for pseudo-poetic sentiment. Play it too big and it comes off sounding inflated. Let the hot air out and the result is a different, truer poetry, the kind that arises from simply showing life as it is. That’s what Messrs. Love and Lancisi and their on- and offstage collaborators have done…

* * *

Read the whole thing here.

The trailer for Everyman Theatre’s productions of Death of a Salesman and A Streetcar Named Desire:

The 1966 TV version of Death of a Salesman, starring Lee J. Cobb and Mildred Dunnock, both of whom created their roles in the original Broadway production:

An ArtsJournal Blog