As of today, Palm Beach Dramaworks’ production of Satchmo at the Waldorf has seven rehearsals to go before our first public preview on May 11. I don’t want to tempt the dark gods of the theater by sounding unreasonably confident, but we do seem to be pretty much where we ought to be at this stage in the process, and I’m now eager to move the show out of the rehearsal room and into the theater. That happens on Thursday, followed two days later by our first technical rehearsal, at which point we’ll start to find out exactly how Satchmo plays when properly lit and accompanied by an appropriately evocative soundtrack.

As of today, Palm Beach Dramaworks’ production of Satchmo at the Waldorf has seven rehearsals to go before our first public preview on May 11. I don’t want to tempt the dark gods of the theater by sounding unreasonably confident, but we do seem to be pretty much where we ought to be at this stage in the process, and I’m now eager to move the show out of the rehearsal room and into the theater. That happens on Thursday, followed two days later by our first technical rehearsal, at which point we’ll start to find out exactly how Satchmo plays when properly lit and accompanied by an appropriately evocative soundtrack.

I can already tell you, though, that Barry Shabaka Henley’s performance is going to be something to see. He was, needless to say, quite remarkably good when we opened Satchmo four months ago at Chicago’s Court Theatre, but his performance in the triple role of Louis Armstrong, Joe Glaser, and Miles Davis has grown richer and more complex now that he has forty performances of the play under his belt. I’ve spent the past week and a half fitting him into the context of my staging, which is significantly different in both appearance and overall tone from the one that was directed by Charles Newell in Chicago. It’s been a pleasure to help him find his footing, though “help” is definitely the operative word: Shabaka has taught me far more about the play than I could ever have told him.

Pleasure, in truth, has been the keynote of our rehearsals in West Palm Beach. Jimmy Danford and Ashley Horowitz, my stage manager and assistant stage manager, are unfailingly nice, superlatively competent collaborators who make hard work feel like a romp in the sandbox. I can’t think of two better people with whom to spend eight hours a day shut up tight in a nondescript rehearsal room, quarrying a familiar script for fresh discoveries. And while directors aren’t supposed to tell tales out of school, I trust that Ashley, whom everyone at Palm Beach Dramaworks from the boss on down described to me as “adorable,” will forgive me for reporting that it’s really, really funny to hear her reading the naughtier lines from Satchmo out loud.

Pleasure, in truth, has been the keynote of our rehearsals in West Palm Beach. Jimmy Danford and Ashley Horowitz, my stage manager and assistant stage manager, are unfailingly nice, superlatively competent collaborators who make hard work feel like a romp in the sandbox. I can’t think of two better people with whom to spend eight hours a day shut up tight in a nondescript rehearsal room, quarrying a familiar script for fresh discoveries. And while directors aren’t supposed to tell tales out of school, I trust that Ashley, whom everyone at Palm Beach Dramaworks from the boss on down described to me as “adorable,” will forgive me for reporting that it’s really, really funny to hear her reading the naughtier lines from Satchmo out loud.

As comfortable as I already feel in the director’s chair, I know that I’m still in the process of learning a brand-new job, and I spend a lot of time each day thinking about how to do it better. One thing that I’ve considered deeply is a piece of advice that Pierre Monteux, a great orchestral conductor who was also a great teacher, gave to André Previn, his best-known pupil. As Previn remembered it:

He liked cloaking his advice with indirection and irony…he saw me conduct a concert with a provincial orchestra. He came backstage after the performance. He paid me some compliments and then asked, “In the last movement of the Haydn symphony, my dear, did you think the orchestra was playing well?” My mind whipped through the movement; had there been a mishap, had something gone wrong? Finally, and fearing the worst, I said that yes, I thought the orchestra had indeed played very well. Monteux leaned toward me conspiratorially and smiled. “So did I,” he said. “Next time, don’t interfere!” It was advice to be followed forever, germinal and important.

So it was, and I am finding that it is no less applicable to the mysterious art of stage direction. When a gifted actor is finding his own way into a part, and you like what he’s doing, the best thing to do is leave him alone and let him do it. The time to put your two cents in is later—if at all.

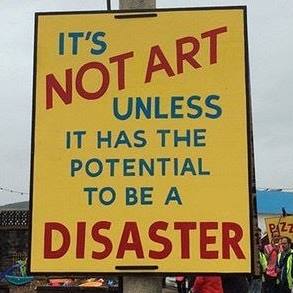

Nobody has to remind me that this is a business in which things can go wrong without the slightest warning. I learned the first time I worked on a play that Murphy’s Law operates as inexorably in the theater as in any other branch of human endeavor, and writing my own shows has retaught me that hard lesson time and again. I hope I’m ready for the curve balls to start flying if and when.

Nobody has to remind me that this is a business in which things can go wrong without the slightest warning. I learned the first time I worked on a play that Murphy’s Law operates as inexorably in the theater as in any other branch of human endeavor, and writing my own shows has retaught me that hard lesson time and again. I hope I’m ready for the curve balls to start flying if and when.

All that said, I still feel after nine rehearsals of Satchmo that directing a play might just be the most fun I’ve ever had in my life, excepting only certain vacations that I’ve taken with Mrs. T. May it prove to be infectious.