Mrs. T has a longstanding weakness for James Bond films, so we watched Thunderball, which I hadn’t seen, the other night. Midway through the film I said to her, “If this damn score doesn’t get out of F minor pretty soon, I’m going to go nuts.” She laughed—not unsympathetically, I think—and rolled her eyes, a decade of life with me having long since accustomed her to such characteristic outbursts.

Mrs. T has a longstanding weakness for James Bond films, so we watched Thunderball, which I hadn’t seen, the other night. Midway through the film I said to her, “If this damn score doesn’t get out of F minor pretty soon, I’m going to go nuts.” She laughed—not unsympathetically, I think—and rolled her eyes, a decade of life with me having long since accustomed her to such characteristic outbursts.

This one arose from the fact that, as H.L. Mencken once put it, the world “presents itself to me, not chiefly as a complex of visual sensations, but as a complex of aural sensations.” But it also served as an unnecessary reminder of how odd I am. I know it isn’t normal to respond to a James Bond movie by complaining about how infrequently the music modulates. Nor did I express my displeasure in anything like a showoffy way: it really did bother me, rather like an unscratchable itch.

I’m not proud to be odd. It’s just something I live with. If anything, it makes me uncomfortable, as I confessed in this space back in 2004:

I’m not proud to be odd. It’s just something I live with. If anything, it makes me uncomfortable, as I confessed in this space back in 2004:

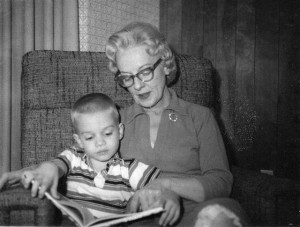

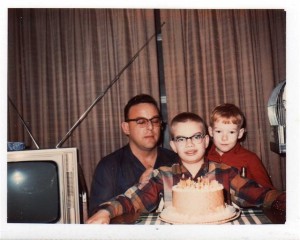

From childhood onward, I was acutely aware of the gap that separated me from my classmates. It’s not that I was treated badly, because I wasn’t. Most of the residents of Smalltown, U.S.A., treated me quite nicely, rather like a cute little dog who could extract square roots with his paw. The problem was that they treated me differently, and once it was clear that I was also musically talented, my situation became impossible. By then, everybody in town knew who I was—Bert and Evelyn’s boy, the smart one—and there was no hiding from my citywide reputation as Smalltown’s number-one egghead.

I hasten to add that there are worse problems than being different. Yet even at the venerable age of sixty, I’m aware at all times of those differences, and I do my best to minimize them in everyday social intercourse. Perhaps because I make my living expressing strong opinions in print, I don’t feel any particular need to express them in conversation with strangers or friendly acquaintances. Indeed, my self-protective streak goes much deeper than that. I’ve learned, for instance, how to simulate interest in pop-culture phenomena about which I know nothing whatsoever, and I can, when absolutely necessary, make myself sound aware of the fact that the Yankees are a baseball team. Nevertheless, it’s an act. I really do spend most of my time thinking about things that don’t matter to at least ninety-nine out of a hundred people, and it really does bother me—not much, but enough to notice—that I do.

What I am, of course, is an aesthete, a person who is mainly interested in beauty, albeit in a way peculiarly resistant to pigeonholing. I once described myself as a “regular-guy aesthete,” which comes as close to the mark as I can get: I like Jean Renoir and John Wayne, and I don’t think my liking for either artist is self-conscious. I like what I like because I like it. Only then do I try to figure out why I like it.

What I am, of course, is an aesthete, a person who is mainly interested in beauty, albeit in a way peculiarly resistant to pigeonholing. I once described myself as a “regular-guy aesthete,” which comes as close to the mark as I can get: I like Jean Renoir and John Wayne, and I don’t think my liking for either artist is self-conscious. I like what I like because I like it. Only then do I try to figure out why I like it.

Even here, though, I tend to swerve well away from the center line, usually in the direction of total immersion. I didn’t look at or think about the visual arts other than in passing until 1995, when I paid a visit to a Kansas City museum where I saw a 1960 painting by Fairfield Porter called “Wheat” that struck me with the force of revelation. Within a year or two I had become a passionate and inveterate museumgoer, and the walls of my apartment were covered with framed posters of paintings by Porter, Milton Avery, Pierre Bonnard, Edgar Degas, Helen Frankenthaler, Hans Hofmann, and Henri Matisse.

Such midlife conversions are far from unusual. But I didn’t stop there: twenty-one years later, I’ve acquired three dozen pieces of art, including prints by all of the aforementioned artists. Most people don’t do that. In fact, none of my close friends collects art, and scarcely any of them know who Fairfield Porter was. Once again, I find myself on the far side of a gap that separates me from most of the rest of the world, and while I am profoundly grateful to have acquired the ability to appreciate painting and sculpture, I am at bottom an essentially conventional person who can’t help but feel that he might well have been more content had his adult life taken a more conventional turn.

George Orwell wrote a poem about this feeling of displacement:

A happy vicar I might have been

Two hundred years ago

To preach upon eternal doom

And watch my walnuts grow.

I, too, might I have been happier if I’d become the small-town schoolteacher that I expected to be, or the lawyer that my father wanted me to be. Instead I became a Manhattan aesthete—though I still don’t feel at home in that skin, or any other. I am, I guess, a rootless wanderer, unexpectedly blessed to be married to a woman who (mostly) likes me as I am, a boon that makes my strangeness easier to accept.

I, too, might I have been happier if I’d become the small-town schoolteacher that I expected to be, or the lawyer that my father wanted me to be. Instead I became a Manhattan aesthete—though I still don’t feel at home in that skin, or any other. I am, I guess, a rootless wanderer, unexpectedly blessed to be married to a woman who (mostly) likes me as I am, a boon that makes my strangeness easier to accept.

Beyond that singular stroke of good fortune, I am lucky to have been taken at something like face value throughout my life. Even in youth, I had plenty of friends, and I have more now than I did then. One of them, Tim Page, learned in adulthood that he suffered from Asperger’s syndrome, about which he wrote a piece in 2007 in which he described the lifelong frustration born of experiencing the world in a way different from everyone else. He was, like me, hopelessly bad at sports, and found the teasing of his playmates to be all but unbearable:

“So?” I wanted to scream. “There are things that I know; things that I can do. Can you name the duet from La Bohème that Antonio Scotti and Geraldine Farrar recorded in Camden, New Jersey, on October 6, 1909? What was the New York address of D. W. Griffith’s first studio? How many books by David Graham Phillips have you read? Who was Adelaide Crapsey? I learned to play the entire Chopin Prelude in E Minor in a single night!” And then tears, of course, and the taunts redoubled.

I never had it that bad, and it helped when I discovered that I had certain talents—most of them having to do with music—that impressed my fellow students. But I also have no explanation for my lifelong strangeness, no clear-cut diagnosis that I can raise as a shield when the going gets awkward. I am, alas, just me, the drama critic-biographer-playwright-director who owns six Fairfield Porter lithographs, gets irritated with Thunderball because too much of the music is in F minor, likes Sausage McMuffins and sushi, and makes a point of watching Hellfighters whenever it turns up on TCM.

I never had it that bad, and it helped when I discovered that I had certain talents—most of them having to do with music—that impressed my fellow students. But I also have no explanation for my lifelong strangeness, no clear-cut diagnosis that I can raise as a shield when the going gets awkward. I am, alas, just me, the drama critic-biographer-playwright-director who owns six Fairfield Porter lithographs, gets irritated with Thunderball because too much of the music is in F minor, likes Sausage McMuffins and sushi, and makes a point of watching Hellfighters whenever it turns up on TCM.

Who he? Damned if I know.

* * *

“Fairfield Porter, Young Man, 1968,” by Youth Trend Report, from the album Life Coach: