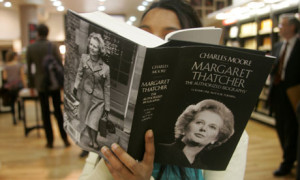

I recently finished reading the first two installments (the third volume has yet to be completed) of Charles Moore’s authorized biography of Margaret Thatcher. Forgive the cliché, but I couldn’t put either book down. I stayed up far too late two nights in a row in order to finish them both—and I’m by no means addicted to political biographies, regardless of subject.

I recently finished reading the first two installments (the third volume has yet to be completed) of Charles Moore’s authorized biography of Margaret Thatcher. Forgive the cliché, but I couldn’t put either book down. I stayed up far too late two nights in a row in order to finish them both—and I’m by no means addicted to political biographies, regardless of subject.

A quarter-century after she left office, Thatcher remains one of the most polarizing figures in postwar history. Because of this, I don’t doubt that many people will have no interest whatsoever in reading a multi-volume biography of her, least of all one whose tone is fundamentally sympathetic. That, however, would be a mistake. Not only does Moore go out of his way to portray Thatcher objectively, but Margaret Thatcher: The Authorized Biography is by any conceivable standard a major achievement, not least for the straightforward, beautifully self-effacing style in which it is written. It is, quite simply, a pleasure to read. Yes, it’s detailed, at times forbiddingly so, but it is, after all, an “official” life, and the level of detail means that you don’t have to know anything about the specific events discussed in the book to be able to understand at all times what Moore is talking about. I confess to having done some skipping, especially in the second volume, but that’s because I expect to return to Margaret Thatcher at least once more in years to come.

One way that Moore leavens the loaf is by being witty, though never obtrusively so. His “jokes” are all bone-dry, and not a few of them consist of merely telling the truth, the best possible way of being funny. A case in point can be found in his account of Thatcher’s support for the unsuccessful Shops Bill, which would have allowed more stores to open on Sundays:

Her personal support for the Bill, which was not enthusiastically backed by her doubting Cabinet, added to the feeling that she was uncaring, that her god was money and even that she was, somehow, un-British. There was hypocrisy in all this, since the great majority of British people, including churchgoers, shopped on Sunday where and when they could; but then hypocrisy is a permanent British quality which politicians ignore at their peril.

He also conveys Thatcher’s exceedingly strong, often headstrong personality with perfect clarity and perfect honesty (or so, at any rate, it seems from a distance). At the same time, he puts that personality in perspective. It is impossible to read far in Margaret Thatcher without realizing that no small part of what made more than a few of Thatcher’s Tory colleagues refer to her as “TBW,” a universally understood acronym for “That Bloody Woman,” was the mere fact that she was a woman—and a middle-class woman to boot. Sexual chauvinism and social snobbery worked against her from the start, not merely from the right but from the left as well (Moore provides ample corroborating evidence of the well-known fact that there is no snob like an intellectual snob). That she prevailed for so long is a tribute to the sheer force of her character. That she was finally booted from office by her fellow Tories says at least as much about them as it does about her.

I found especially fascinating the chapter of the first volume in which Moore describes in detail the simple manner in which Thatcher and her family lived in the upstairs apartment of 10 Downing Street. Not being a Brit, it was all news to me, and it says much about her deep middle-class roots, of which she was not even slightly ashamed:

I found especially fascinating the chapter of the first volume in which Moore describes in detail the simple manner in which Thatcher and her family lived in the upstairs apartment of 10 Downing Street. Not being a Brit, it was all news to me, and it says much about her deep middle-class roots, of which she was not even slightly ashamed:

The flat, which was at the top of the house, was small and almost poky….Its kitchen was no more than a galley. It suited Mrs. Thatcher, however. She liked the idea of “living over the shop,” as in her Grantham childhood, and the convenience of being so close to the work she loved….Due to the remarkable strictness of government rules on such matters, the Thatchers were provided with no help of any kind in looking after their flat. They paid cleaning women themselves, and it fell to them, in practice to Mrs Thatcher herself, since [her husband] Denis had old-fashioned views on these matters, to procure, generally with the help of Caroline Stephens and more junior secretaries, their own food and cook it….

Tessa Jardine-Paterson, who came as a political secretary after having worked for Mrs. Thatcher in Parliament, remembered that she and her colleagues always saw it as part of their jobs to rustle up drinks and even meals for Mrs. Thatcher. They felt perfectly happy to do so because she herself was so unsnooty in her readiness to help in such matters, often plunging her hands into the sink to wash up with the words “It’s much easier to do it yourself.”

Were such things to be written of an American politican, I would instantly assume them to be a product of the spin factory, but to read Margaret Thatcher is to take them at face value. She was, it seems, nothing more or less than that kind of person, a grocer’s daughter who graduated from Oxford and climbed to the highest rung of democratic power without ever losing sight of where she came from or what she believed in. This, for good or ill, was the wellspring of Thatcher’s popularity—and many younger readers, especially those who only “know” her from the hostile caricatures of her political enemies, will likely have no notion of how hugely popular she was.

I also find it fascinating that Moore confirms what I had long heard from other sources, which is that Thatcher was widely thought to be a very attractive woman. To be sure, her photographs give no clue to the nature of her allure, at least from the point of view of an American eye, but one cannot doubt that many men—not all of whom were disposed to like her—were susceptible to her feminine charms. Indeed, the following footnote, which is characteristic of Moore’s poker-faced sense of humor and which I quote in its entirety, made me laugh out loud:

I also find it fascinating that Moore confirms what I had long heard from other sources, which is that Thatcher was widely thought to be a very attractive woman. To be sure, her photographs give no clue to the nature of her allure, at least from the point of view of an American eye, but one cannot doubt that many men—not all of whom were disposed to like her—were susceptible to her feminine charms. Indeed, the following footnote, which is characteristic of Moore’s poker-faced sense of humor and which I quote in its entirety, made me laugh out loud:

A significant factor in Mrs. Thatcher’s political success was that quite large numbers of men fell for her. The Scottish genealogist Sir Ian Moncreiffe of that Ilk was the only man known to have made an indecent suggestion to her while she was Prime Minister, but many harboured a romantic devotion which teetered on the edge of the sexual. Sir Hector (later Lord) Laing, the chairman of United Biscuits, would send her notes which he requested be placed under her pillow. Kingsley Amis, the novelist, described Mrs. Thatcher as “one of the best-looking women I had ever met…The fact that it is not a sensual or sexy beauty does not make it a less sexual beauty, and that sexuality is still, I think, an underrated factor in her appeal (or repellence)” (Kingsley Amis, Memoirs, Hutchinson, 1991, p. 316). Brian Walden reported David Owen as saying to him: “The whiff of that perfume, the sweet smell of whisky. By God, Brian, she’s appealing beyond belief” (interview with Brian Walden). Alan Clark, when asked by the present author about the nature of his love for Mrs. Thatcher, said: “I don’t want actual penetration—just a massive snog.”

The Brits, they are a funny race.