On Sunday I flew up to Chicago to see back-to-back preview performances of the Court Theatre’s all-new production of Satchmo at the Waldorf, directed by Charles Newell, which opens on Saturday. By then I’d seen several dozen performances of Satchmo’s previous iteration, the off-Broadway production directed by Gordon Edelstein that has also been mounted in Lenox, New Haven, Philadelphia, and Los Angeles and will be opening next Wednesday at San Francisco’s American Conservatory Theater. It’d be hard to come up with two more dissimilar ways of staging the same show.

Gordon’s Satchmo, whose set was designed by Lee Savage, is for the most part naturalistic in approach. It takes place in a dressing room that is specifically intended to suggest a room at New York’s Waldorf-Astoria Hotel, in whose Empire Room Louis Armstrong played his last gig in March of 1971, four months before his death. As part of his preparation for designing the set, Lee studied period photographs of the Waldorf, and he made every possible effort to create a performing space that has “Waldorf ” written all over it, right down to the tiniest of details. Armstrong’s dressing-room table is strewn with objects closely similar to the ones that can be seen in surviving photographs of his real-life dressing rooms and hotel rooms, and John Gromada, the sound designer, accompanied the production with a well-chosen selection of excerpts from Armstrong’s recordings. The goal was to make Satchmo look and sound as realistic as possible, and I think we succeeded. The sink even works!

Gordon’s Satchmo, whose set was designed by Lee Savage, is for the most part naturalistic in approach. It takes place in a dressing room that is specifically intended to suggest a room at New York’s Waldorf-Astoria Hotel, in whose Empire Room Louis Armstrong played his last gig in March of 1971, four months before his death. As part of his preparation for designing the set, Lee studied period photographs of the Waldorf, and he made every possible effort to create a performing space that has “Waldorf ” written all over it, right down to the tiniest of details. Armstrong’s dressing-room table is strewn with objects closely similar to the ones that can be seen in surviving photographs of his real-life dressing rooms and hotel rooms, and John Gromada, the sound designer, accompanied the production with a well-chosen selection of excerpts from Armstrong’s recordings. The goal was to make Satchmo look and sound as realistic as possible, and I think we succeeded. The sink even works!

In a sense, Gordon’s straightforward, no-nonsense staging emanated from the design. Needless to say, the audience has to make a huge imaginative leap in order to “buy” the theatrical conceit of the play, in which a single actor switches back and forth without warning between Armstrong, Joe Glaser, and Miles Davis. But Lee’s set and Kevin Adams’ lighting plot underline every character change, and to date our audiences seem not to have any trouble keeping up with the action.

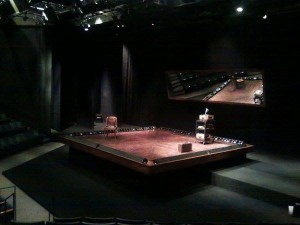

Charlie’s production of Satchmo, whose set was designed by John Culbert, is as expressionistic as Gordon’s production is naturalistic. It takes place on an elevated, all-but-bare playing area that is surrounded on all four sides by footlights. A huge upstage mirror is carefully positioned to reflect the onstage action in a way that is visible to everyone in the audience. Keith Parham’s sharp-angled lighting is unabashedly theatrical—his use of shadows is straight out of film noir—and Andre Pluess, the sound designer, has accompanied the show with a thickly layered mix of recordings by Armstrong, electronic music, and sound effects, some of them realistic and others almost hallucinatory. In a sense, the sound is the scenery: it hints at where we are and what is happening there.

Charlie’s production of Satchmo, whose set was designed by John Culbert, is as expressionistic as Gordon’s production is naturalistic. It takes place on an elevated, all-but-bare playing area that is surrounded on all four sides by footlights. A huge upstage mirror is carefully positioned to reflect the onstage action in a way that is visible to everyone in the audience. Keith Parham’s sharp-angled lighting is unabashedly theatrical—his use of shadows is straight out of film noir—and Andre Pluess, the sound designer, has accompanied the show with a thickly layered mix of recordings by Armstrong, electronic music, and sound effects, some of them realistic and others almost hallucinatory. In a sense, the sound is the scenery: it hints at where we are and what is happening there.

Do I prefer one version over the other? No. Both productions seem to me to be completely and equally valid, each in its own way. I wouldn’t want to have choose between them—and I don’t have to choose. As soon as we open Charlie’s Satchmo in Chicago, I’ll fly out to San Francisco to open Gordon’s Satchmo. I’m thrilled at the prospect of the juxtaposition.

To be sure, my personal taste runs more to the poetic abstraction of lyric theater, and Charlie’s Satchmo is poetic—and beautiful—beyond anything I could possibly have imagined. But I also adore smell-the-coffee kitchen-sink realism when it’s done well, and Gordon and his design team did it really, really well. As my Louis Armstrong says when describing the introductory trumpet cadenza of “West End Blues,” by the time you get to the end of their version of the show, “you know you done been somewhere.”

All this is of particular relevance to me because I’ll be directing my own production of Satchmo at Palm Beach Dramaworks later this year. I’ve spent a lot of time talking to Michael Amico, the set designer, about how we want our Satchmo to look, and he e-mailed me his first preliminary sketch of the set on Saturday. Our plan at present is to split the difference, so to speak, between Gordon and Charlie: the Palm Beach Satchmo will be naturalistic, but in a looser, less historically specific way.

All this is of particular relevance to me because I’ll be directing my own production of Satchmo at Palm Beach Dramaworks later this year. I’ve spent a lot of time talking to Michael Amico, the set designer, about how we want our Satchmo to look, and he e-mailed me his first preliminary sketch of the set on Saturday. Our plan at present is to split the difference, so to speak, between Gordon and Charlie: the Palm Beach Satchmo will be naturalistic, but in a looser, less historically specific way.

And how well will that work? Your guess is as good as mine. But I do know that whatever its ultimate value as a play, Satchmo at the Waldorf has so far proved strong enough to have inspired two full-scale productions that are radically different in appearance and approach, as well as a small-scale version, the 2011 Orlando premiere, that was directed by Rus Blackwell and designed by William Elliot. Staged in a tiny cabaret-style black-box theater, the first Satchmo presented the show in a much more intimate (but similarly convincing) manner.

And how well will that work? Your guess is as good as mine. But I do know that whatever its ultimate value as a play, Satchmo at the Waldorf has so far proved strong enough to have inspired two full-scale productions that are radically different in appearance and approach, as well as a small-scale version, the 2011 Orlando premiere, that was directed by Rus Blackwell and designed by William Elliot. Staged in a tiny cabaret-style black-box theater, the first Satchmo presented the show in a much more intimate (but similarly convincing) manner.

Am I a good enough director to find a fourth, comparably persuasive way to thread the needle? We’ll see. The mere fact that I wrote the play, though, is no guarantee that I have anything original to say about it as a director, nor do I think that my interpretation of Satchmo must necessarily be “right.” The author doesn’t always know best! So when I go down to Palm Beach to stage the show, I intend to approach the script as if it had been written by another person. Insofar as possible, I want to try to see it fresh.

Between them, Gordon, Charlie, Rus, and their respective design teams have now taught me a vast amount about unearthing the directorial possibilities in a play. The rest is up to Michael and me.

* * *

Hearst Metrotone News’ Louis Armstrong obituary, released in 1971. This featurette contains what is thought to be the only surviving film footage shot at Armstrong’s last gig at the Waldorf-Astoria, as well as scenes from his funeral in New York, at which Peggy Lee sang “The Lord’s Prayer.” The eulogy was delivered by Fred Robbins: