Otto Klemperer is interviewed by John Freeman on Face to Face, originally telecast on the BBC in 1961:

Otto Klemperer is interviewed by John Freeman on Face to Face, originally telecast on the BBC in 1961:

(This is the latest in a series of arts-related videos that appear in this space each Monday, Wednesday, and Friday.)

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City

“The actor’s technique is that personal and very private means by which you get the best out of yourself. Every actor does it differently. There’s never been an artist alive who didn’t have to deal with form and content. Those who deal only with content are the ones who act with their guts, but who’s interested in their guts? We’re interested in Hamlet’s guts, or Richard III’s guts, and you have to be heard in the back row. Of course you must have content, but you’ve got to have form. The thing is to marry the two so the form isn’t noticed. Form without content, forget it.”

“The actor’s technique is that personal and very private means by which you get the best out of yourself. Every actor does it differently. There’s never been an artist alive who didn’t have to deal with form and content. Those who deal only with content are the ones who act with their guts, but who’s interested in their guts? We’re interested in Hamlet’s guts, or Richard III’s guts, and you have to be heard in the back row. Of course you must have content, but you’ve got to have form. The thing is to marry the two so the form isn’t noticed. Form without content, forget it.”

Hume Cronyn (quoted in the New York Times, June 17, 2003)

Mrs. T and I have just added a new piece to the Teachout Museum, a posthumous impression of an unsigned drypoint by Berthe Morisot, a member of the original circle of French Impressionists. It was made in 1888 or 1889 and is variously known as “Jeune fille au chat,” “Fillette au chat (Julie Manet),” and “Young Girl with a Cat, after a portrait of Julie Manet by Renoir.” It is, as the third of these titles indicates, based on an 1887 painting by Renoir called “Julie Manet” that is owned by the Musée d’Orsay. The long version of the title is the one used by the Metropolitan Museum of Art, which acquired its copy in 1922.

Mrs. T and I have just added a new piece to the Teachout Museum, a posthumous impression of an unsigned drypoint by Berthe Morisot, a member of the original circle of French Impressionists. It was made in 1888 or 1889 and is variously known as “Jeune fille au chat,” “Fillette au chat (Julie Manet),” and “Young Girl with a Cat, after a portrait of Julie Manet by Renoir.” It is, as the third of these titles indicates, based on an 1887 painting by Renoir called “Julie Manet” that is owned by the Musée d’Orsay. The long version of the title is the one used by the Metropolitan Museum of Art, which acquired its copy in 1922.

We saw Morisot’s print for the first time on a recent visit to Pittsburgh’s Carnegie Museum of Art, where it is proudly hung. Here’s what the Carnegie Museum has to say about “Jeune fille au chat” in its online catalogue:

Known primarily for her paintings of domestic life, Berthe Morisot began experimenting with printmaking in the late 1880s at the encouragement of her Impressionist colleagues. In this drypoint, Morisot lightly sketches her daughter, Julie Manet, a frequent subject of her works. She was Morisot’s only child and the niece of Édouard Manet. Beginning around 1888, Morisot made 12 known etching and drypoint plates, which were deposited with renowned publisher Ambroise Vollard after her death in 1895. Vollard had small editions of her plates printed. The two dots, at the upper center and the lower center, indicate that the print belongs to the posthumous edition produced by Vollard.

Renoir’s original is lovely and characteristic, but Morisot has in my opinion improved on it by turning his painting into a drypoint, in the process making it at once crisper and (dare I say it?) less obviously sentimental. Julie Manet recalled that Renoir painted the portrait “in small sections, which was not his usual way of working. I thought it was a good resemblance, but when Degas saw it he complained: ‘By doing round faces, Renoir produces flower pots.’”

Renoir’s original is lovely and characteristic, but Morisot has in my opinion improved on it by turning his painting into a drypoint, in the process making it at once crisper and (dare I say it?) less obviously sentimental. Julie Manet recalled that Renoir painted the portrait “in small sections, which was not his usual way of working. I thought it was a good resemblance, but when Degas saw it he complained: ‘By doing round faces, Renoir produces flower pots.’”

I might add that Renoir’s Julie, as was his wont, is an idealized vision of a pretty young girl, whereas Morisot’s Julie is a real person, so real that she all but leaps out of the frame. No doubt this has something to do with the fact that Morisot was Julie’s mother: she knew her better.

Here’s what I wrote about the print in this space two months ago, a few days after seeing it in Pittsburgh:

Here’s what I wrote about the print in this space two months ago, a few days after seeing it in Pittsburgh:

Morisot tends to get short shrift in discussions of the French impressionists, no doubt in part because she was a woman but also because of the soft-spoken intimacy of her work. The CMA also owns a spectacular Monet water-lily panel in front of which Mrs. T and I lingered, but we came back to “Young Girl with a Cat” twice, and I felt even more strongly on a second viewing that I could look at it every day. Aside from its sheer elegance of execution, I delighted in the sharp features of the young girl portrayed therein. If there is such a thing as a quintessentially French face, Julie Manet had one, and Morisot, her mother, managed to catch it on the etching plate.

When a beautifully framed copy came up for auction in Connecticut this past weekend, I decided to bid on it, and knocked it down for—believe it or not—one hundred dollars. Never let it be said that it isn’t possible to buy classy art on the cheap!

The trouble with my life is not that it’s dull but that it sometimes becomes too interesting, at which point successive waves of beauty can start looking suspiciously like one damn thing after another. Experience has taught me the dangers of overscheduling myself, but though I’ve learned the lesson fairly well, it doesn’t always stop me from signing up for one event too many. Nor do I ever have total control over my schedule: press previews and deadlines fall where they will, not where I would, and every once in a while they become fused with the other parts of my life in such a way as to rob me of the ability to fall asleep. “Oh, God, I’m wired,” I find myself muttering grimly at three in the morning, knowing I’ll have to go on booming and zooming for several days past the last deadline before the adrenalin finally leaches out of my pores and I become my even-keeled self once more….

Read the whole thing here.

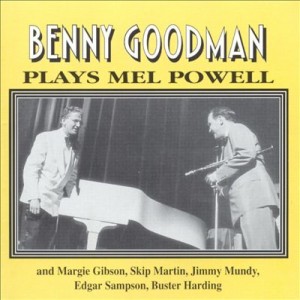

I had occasion the other day to Google Mel Powell, a child prodigy who became Benny Goodman’s pianist (and a fabulous one, too) at the age of seventeen. Seven years later he switched hats, went to Yale to study composition with Paul Hindemith, started writing classical music, and eventually gave up jazz.

I had occasion the other day to Google Mel Powell, a child prodigy who became Benny Goodman’s pianist (and a fabulous one, too) at the age of seventeen. Seven years later he switched hats, went to Yale to study composition with Paul Hindemith, started writing classical music, and eventually gave up jazz.

I mention all this because one of the things I learned when I Googled Powell was that I’d written a piece about him in 1998 for the Sunday New York Times—a piece I have no memory of writing, even though it sounds just like me:

Trivia question: who was the first jazz musician to win the Pulitzer Prize for music? Hint: it wasn’t Wynton Marsalis. The honor belongs to Mel Powell, who won in 1990 for a two-piano concerto called Duplicates. To be sure, the composer of Duplicates had long since stopped playing jazz by the time he collected his prize. But Powell, who worked with Benny Goodman and Glenn Miller in the 1940s, was for a brief time among the best-known big-band sidemen in America, and when he died on April 24, jazz connoisseurs mourned him not as a relatively obscure composer of nontonal classical music, but as one of the most underrated pianists of the swing era.

When I was younger, I would have boggled at the thought that I might someday forget having written such a piece. Now I know better. In the last twelve years alone, I’ve written close to a thousand columns for The Wall Street Journal and more than eleven thousand postings in this space, not to mention my monthly essays for Commentary and fugitive writings for sundry other magazines and newspapers. What’s surprising isn’t that I forgot having written about Mel Powell, but that I can still remember—usually—what I wrote about last week.

Compared to the true writing machines of the past, of course, I’m a piker. Rex Stout, about whom I’m giving a lecture on Saturday, published thirty-three full-length novels and some forty-odd novellas about Nero Wolfe and Archie Goodwin between 1934 and his death in 1974. H.L. Mencken claimed in the preface to A Mencken Chrestomathy that “the total of my published writings…must run well beyond 5,000,000 words,” an estimate that doubtless fell far short of the actual mark.

Compared to the true writing machines of the past, of course, I’m a piker. Rex Stout, about whom I’m giving a lecture on Saturday, published thirty-three full-length novels and some forty-odd novellas about Nero Wolfe and Archie Goodwin between 1934 and his death in 1974. H.L. Mencken claimed in the preface to A Mencken Chrestomathy that “the total of my published writings…must run well beyond 5,000,000 words,” an estimate that doubtless fell far short of the actual mark.

I can’t claim to come anywhere near such stupendous totals. Still, any reasonably hard-working newspaperman can expect to hit the million-word mark sooner or later if he lives long enough, and I’m sure I passed mine long ago. I started writing for money, after all, in 1977, when I was twenty-one years old. My very first piece was a Kansas City Star review of a classical violinist whose name I no longer remember, though I do recall that he played Richard Strauss’ Violin Sonata, a piece I didn’t like in 1977 and don’t like any better now. I reviewed several hundred classical and jazz performances between then and 1983, carefully clipping copies of each review and mounting them in a pair of fat scrapbooks. By the end of that time I’d also started to write for magazines, and for many years I saved those pieces as well. At one point I went so far as to compile a typewritten bibliography of my magazine articles, an admission that I now blush to make.

I threw out my Kansas City Star scrapbooks and the pile of magazines containing my pieces when, in 2004, I published A Terry Teachout Reader, which contained most of the magazine and newspaper articles written prior to that time that I thought worth preserving. By then it had become apparent that the remainder of my oeuvre would someday be available via searchable online archives, and that there was thus no reason for me to hang onto paper copies of any of it.

More to the point, I was old enough in 2004 to have finally figured out that journalism, mine included, is written to be forgotten. Any journalist who thinks otherwise is kidding himself. Even Mencken, who had a robust ego and did manage to write a few things that seem destined to last, cheerfully admitted in A Mencken Chrestomathy that most of the mountain of words he had piled up between 1899 and 1948 amounted to nothing more than “journalism pure and simple—dead almost before the ink which printed it was dry.”

My own mountain will be no more enduring. As I once wrote in this space, I’d venture to guess that I’ll be better “remembered” over the long haul for having owned one or two pieces of art than for having written anything in the Teachout Reader, and I can’t imagine that my other books will live any longer. How fitting, then, that I should be spending the present and (I assume) final part of my life working in and chronicling the theater, that most radically evanescent of art forms, which exists, like journalism, in the moment and leaves no trace save for fragments of memory and a very short stack of time-defying scripts.

A friend recently sent me a copy of Letters from an Actor, a book written in 1966 by William Redfield, a little-known but once-respected stage actor who is now remembered, if at all, for appearing in the 1975 film version of One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest. In addition, Redfield played Guildenstern in John Gielgud’s modern-dress 1964 Broadway production of Hamlet, in which Richard Burton essayed the title role, and in Letters from an Actor he set down his pungent recollections of what it was like to rehearse that hugely successful but artistically ill-fated staging. He also wrote beautifully—and memorably—about his decision to devote his life to a profession in which virtually all of his achievements were writ on water:

A friend recently sent me a copy of Letters from an Actor, a book written in 1966 by William Redfield, a little-known but once-respected stage actor who is now remembered, if at all, for appearing in the 1975 film version of One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest. In addition, Redfield played Guildenstern in John Gielgud’s modern-dress 1964 Broadway production of Hamlet, in which Richard Burton essayed the title role, and in Letters from an Actor he set down his pungent recollections of what it was like to rehearse that hugely successful but artistically ill-fated staging. He also wrote beautifully—and memorably—about his decision to devote his life to a profession in which virtually all of his achievements were writ on water:

Acting is the most mortal of the arts. Like perishable foods, it must be taken fresh or not at all….Line drawings, quick sketches. An intuitive understanding of what reaches people today—loving, hating, and struggle. The actor must be deep in his heart and quick with his hands, catch Pegasus by the heel by riding a tiger, have the soul of a fairy and the hide of a walrus, change himself from night to night and alter his psyche from year to year. He is a chameleon gone aesthetic; a shade with a purpose. A second-story man who breaks into your house not to take but to give. Actors who do not keep pace with today will go under. Like lemmings, they will drown even in the neap tide. For the actor, today is the future.

So, too, for the journalist—and yet there are far worse fates than to be forced to live in an unending succession of moments. As insignificant as I am in the grand scheme of things, I still think—I hope—that I help in my little way to make the world of art a better place. And if not? Then my failed attempts will crumble into dust soon enough.

As for Mel Powell, he left us in 1998. His death, in fact, was the occasion for the New York Times tribute that I forgot having written. But the improvised-on-the-spot solos that he recorded in the Forties and Fifties are still with us, and still marvelous to hear. Famous he isn’t, but neither is he altogether forgotten. I should be so lucky.

* * *

Benny Goodman, Lionel Hampton, and Mel Powell play “Stealin’ Apples” in the 1948 film A Song Is Born, directed by Howard Hawks and starring Danny Kaye:

Benny Goodman and Mel Powell play together on The Merv Griffin Show in 1976:

An excerpt from a film of a live stage performance of John Gielgud’s 1964 production of Hamlet, with Richard Burton in the title role, Hume Cronyn as Polonius, Clement Fowler as Rosencrantz, and William Redfield as Guildenstern:

Jacques d’Amboise dances three excerpts from George Balanchine’s Apollo, set to a score by Igor Stravinsky. Melissa Hayden is Terpsichore, Jillana is Calliope, and Patricia Neary is Polyhymnia. This performance was originally telecast on The Bell Telephone Hour on January 18, 1963. Jean Casadesus, Patti Page, and Fred Waring and the Pennsylvanians also appeared on the same program:

Jacques d’Amboise dances three excerpts from George Balanchine’s Apollo, set to a score by Igor Stravinsky. Melissa Hayden is Terpsichore, Jillana is Calliope, and Patricia Neary is Polyhymnia. This performance was originally telecast on The Bell Telephone Hour on January 18, 1963. Jean Casadesus, Patti Page, and Fred Waring and the Pennsylvanians also appeared on the same program:

(This is the latest in a series of arts-related videos that appear in this space each Monday, Wednesday, and Friday.)

| M | T | W | T | F | S | S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | |||||

| 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

| 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 |

| 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 |

| 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | ||

An ArtsJournal Blog