“Dottie was always saying that she loved to entertain graciously, and by this she meant that she liked to do things with a sort of weight-throwing ostentation attributable to her simple beginnings.”

“Dottie was always saying that she loved to entertain graciously, and by this she meant that she liked to do things with a sort of weight-throwing ostentation attributable to her simple beginnings.”

John P. Marquand, Melville Goodwin, USA

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City

The Wall Street Journal has given me an extra drama column today to report on two Broadway openings, An American in Paris and It Shoulda Been You. One’s a triumph, the other a clunker. Here’s an excerpt.

* * *

Christopher Wheeldon, the most prodigiously talented ballet choreographer of his generation, has followed in the giant footsteps of Jerome Robbins, his one-time mentor, by directing a Broadway show. “An American in Paris,” a new theatrical version of Gene Kelly’s Gershwin-themed 1951 screen musical, instantly catapults Mr. Wheeldon into the ranks of top-tier director-choreographers, by which I mean Robbins and Bob Fosse. It’s been years—decades, really—since I last saw production numbers that were infused with the kind of rich, sustained creativity that Mr. Wheeldon gives us throughout “An American in Paris.” This is what musical-comedy dance can look like when it’s made by a choreographer who knows how to do more than just stage a song. Once you’ve seen it, you’ll know what you’ve been missing, and find it hard ever again to settle for less.

Christopher Wheeldon, the most prodigiously talented ballet choreographer of his generation, has followed in the giant footsteps of Jerome Robbins, his one-time mentor, by directing a Broadway show. “An American in Paris,” a new theatrical version of Gene Kelly’s Gershwin-themed 1951 screen musical, instantly catapults Mr. Wheeldon into the ranks of top-tier director-choreographers, by which I mean Robbins and Bob Fosse. It’s been years—decades, really—since I last saw production numbers that were infused with the kind of rich, sustained creativity that Mr. Wheeldon gives us throughout “An American in Paris.” This is what musical-comedy dance can look like when it’s made by a choreographer who knows how to do more than just stage a song. Once you’ve seen it, you’ll know what you’ve been missing, and find it hard ever again to settle for less.

I should immediately add, though, that you needn’t know anything about ballet to fall for “An American in Paris,” any more than you have to be a dance critic to love the Fred Astaire-Ginger Rogers movies. It’s a diamond-studded jukebox musical, a boy-meets-girl tale set to the songs of George Gershwin that has been designed to super-spectacular effect by Bob Crowley. Robert Fairchild, the New York City Ballet principal dancer who has been cast as Jerry Mulligan, the American artist played by Kelly in the film, is an unbelievable find, a virtuoso hoofer who also sings and acts with Kelly’s nonchalant flair….

Craig Lucas’ book is a snout-to-tail rewrite of Alan Jay Lerner’s fluffy screenplay, to which Mr. Lucas has added a sometimes heavy-handed but mostly welcome touch of grit, resetting the show in the twilight world of collaborators and concealed Jews that was Paris in 1945. The heightened dramatic stakes of his new plot justify the heightened emotions of Mr. Wheeldon’s dance sequences, the most extraordinary of which is the climactic 13-minute title ballet. In an act of supreme imaginative daring, Mr. Wheeldon has turned Gershwin’s 1928 tone poem into a plotless neoclassical ballet in the style of George Balanchine—but one that doubles as a symbolic reenactment of the love story of Jerry and Lise. Not since “West Side Story” has dance been used to such overwhelming effect on Broadway….

Craig Lucas’ book is a snout-to-tail rewrite of Alan Jay Lerner’s fluffy screenplay, to which Mr. Lucas has added a sometimes heavy-handed but mostly welcome touch of grit, resetting the show in the twilight world of collaborators and concealed Jews that was Paris in 1945. The heightened dramatic stakes of his new plot justify the heightened emotions of Mr. Wheeldon’s dance sequences, the most extraordinary of which is the climactic 13-minute title ballet. In an act of supreme imaginative daring, Mr. Wheeldon has turned Gershwin’s 1928 tone poem into a plotless neoclassical ballet in the style of George Balanchine—but one that doubles as a symbolic reenactment of the love story of Jerry and Lise. Not since “West Side Story” has dance been used to such overwhelming effect on Broadway….

“It Shoulda Been You” is a plastic statuette for the tourist trade, a nice-Jewish-girl-marries-nice-Catholic-boy musical farce that is by turns desperately unfunny and relentlessly preachy. Brian Hargrove’s been-there-done-that plot (Tyne Daly’s Jewish mom is a monster of tactlessness, Harriet Harris’ Catholic mom a boozehound) was already a cliché a half-century ago, and today its whiskery stereotypes are a millimeter away from being actively offensive. As for Barbara Anselmi’s music, it sounds like a medley of discarded theme songs from the pilots of failed ‘70s sitcoms….

* * *

To read my complete review of An American in Paris, go here.

To read my complete review of It Shoulda Been You, go here.

The trailer for An American in Paris:

“There always came a time when you wearied of listening to the fallacies of self-justification because you learned finally the basic truth that no one in a jam was in a position to give you anything back. Such people were too busy with their own vagaries even for true gratitude. In the end they always did what they desired, and they might as well have done it from the first instead of making it a problem.”

“There always came a time when you wearied of listening to the fallacies of self-justification because you learned finally the basic truth that no one in a jam was in a position to give you anything back. Such people were too busy with their own vagaries even for true gratitude. In the end they always did what they desired, and they might as well have done it from the first instead of making it a problem.”

John P. Marquand, Melville Goodwin, USA

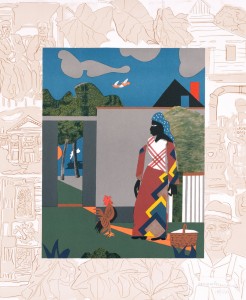

I mentioned the other day that Mrs. T and I were thinking about adding a new piece to the Teachout Museum. After long and careful consideration, we decided to take the plunge and place a bid, and we are now the proud owners of a signed copy of “Pepper Jelly Lady,” a 1980 lithograph by Romare Bearden that is also part of the collection of the Smithsonian American Art Museum.

I mentioned the other day that Mrs. T and I were thinking about adding a new piece to the Teachout Museum. After long and careful consideration, we decided to take the plunge and place a bid, and we are now the proud owners of a signed copy of “Pepper Jelly Lady,” a 1980 lithograph by Romare Bearden that is also part of the collection of the Smithsonian American Art Museum.

Based on one of Bearden’s boldly colored cubist collages, “Pepper Jelly Lady” shows a West Indian woman selling homemade jelly in front of a walled estate. It was originally part of a portfolio of six prints by Bearden, Ansel Adams, Audrey Flack, Sam Francis, Robert Indiana, and Wayne Thiebaud that were created by the artists to be sold by the Democratic Committee Service Corporation to raise funds for Jimmy Carter’s 1980 presidential campaign. This particular lithograph exemplifies the Louis Armstrong-like optimism of Bearden’s work, in which the black experience in America is portrayed honestly but hopefully. “Even though you go through these terrible experiences, you come out feeling good,” he once said. “That’s what the blues say and that’s what I believe—life will prevail. That’s why I’ve gone back to the South and to jazz.”

One of Bearden’s most admired prints, “Pepper Jelly Lady” was chosen for inclusion in “A Graphic Odyssey: Romare Bearden as Printmaker,” a large-scale traveling exhibit of more than one hundred lithographs, monoprints, collagraphs, screenprints, and etchings that toured the United States in 1994 and 1995. Holland Cotter reviewed “A Graphic Odyssey” for The New York Times, and “Pepper Jelly Lady” figured in his review:

One of Bearden’s most admired prints, “Pepper Jelly Lady” was chosen for inclusion in “A Graphic Odyssey: Romare Bearden as Printmaker,” a large-scale traveling exhibit of more than one hundred lithographs, monoprints, collagraphs, screenprints, and etchings that toured the United States in 1994 and 1995. Holland Cotter reviewed “A Graphic Odyssey” for The New York Times, and “Pepper Jelly Lady” figured in his review:

The show opens with prints based on Bearden’s childhood. In “Quilting Time”—whose composition Bearden used in a painting, a mosaic and a lithograph—two women bend over their sewing in a small house as a pink sunset sky glows outside the window. In “Pepper Jelly Lady” a figure in a dashingly patterned dress is framed by a wide border filled with drawings of Southern life: a plain wooden church, a porticoed mansion, a room with a potbellied stove….

Bearden considered himself an essentially American artist, and relished the ingredients in his own life that defined that odd collage of an identity: North Carolina and Paris; Melville and Billie Holiday; Buddhism and the Bible; Matisse and African masks. Although rarely a polemicist, he was alert to political realities. Artistically a traditionalist, his daring was to combine a wide range of traditions: traces of European, African, Asian and American cultures mingle in his prints like a rich perfume.

Mrs. T and I are delighted to be able to hang on our walls so beautiful a work by one of America’s greatest artists.

I like Antonio’s, mostly because it reminds me of all the other barber shops I’ve visited regularly. Not the mall-type franchise stores that I patronized in college–I never liked those–but the ones in Smalltown, U.S.A., where I got my hair trimmed in the company of older men who chatted pleasantly about matters of no interest as the radio purred softly in the background. I found a place like that when I first moved to New York twenty years ago, and last year I found another one in my own neighborhood. You don’t hear much English at Antonio’s, just the soothing murmur of Spanish-language conversations whose subject matter is scarcely less intelligible to me than the talk of business and sports that I recall from my Smalltown days….

Read the whole thing here.

“It was no one’s fault that it was hard to keep memories of wives perpetually green in that extreme and changing environment, even with the aid of the photographs and love-gauges that one carried overseas. The European Theater of Operations was not a place where home ties fitted into a successful design for living. Memory interfered with work, and if you thought too much about past domesticity, you became a maladjusted burden. Instead it was advisable to think of home as a Never-Never Land, and of your present milieu as a region with drives and emotional values that no one at home could possibly comprehend It was just as well to believe that the things you did and said in this milieu into which you were thrust in order to keep your land safe and your loved ones secure, would have no effect whatsoever on what went on at home. Some day we would all get safely back to that Never-Never Land. Some might never return, but this would not be true of us as individuals. We would get bak, and this Great Adventure would be the tale of an idiot. If you did not have this philosophy, you would not be a useful soldier.”

“It was no one’s fault that it was hard to keep memories of wives perpetually green in that extreme and changing environment, even with the aid of the photographs and love-gauges that one carried overseas. The European Theater of Operations was not a place where home ties fitted into a successful design for living. Memory interfered with work, and if you thought too much about past domesticity, you became a maladjusted burden. Instead it was advisable to think of home as a Never-Never Land, and of your present milieu as a region with drives and emotional values that no one at home could possibly comprehend It was just as well to believe that the things you did and said in this milieu into which you were thrust in order to keep your land safe and your loved ones secure, would have no effect whatsoever on what went on at home. Some day we would all get safely back to that Never-Never Land. Some might never return, but this would not be true of us as individuals. We would get bak, and this Great Adventure would be the tale of an idiot. If you did not have this philosophy, you would not be a useful soldier.”

John P. Marquand, Melville Goodwin, USA

Mrs. T and I missed the worst of the horrific winter just past, but we were intensely aware at all times of its viciousness. No sooner did we return from Florida at the beginning of March than our noses were rubbed in it, since we had to drive through what amounted to a tunnel of snow to get to our little farmhouse in rural Connecticut. Even now, six weeks later, a substantial patch of not-quite-white snow continues to cling insolently to the ground, and when we drove up to Connecticut last Sunday and saw snowflakes on the windshield of our car as we passed through Hartford, I briefly felt like crying.

Mrs. T and I missed the worst of the horrific winter just past, but we were intensely aware at all times of its viciousness. No sooner did we return from Florida at the beginning of March than our noses were rubbed in it, since we had to drive through what amounted to a tunnel of snow to get to our little farmhouse in rural Connecticut. Even now, six weeks later, a substantial patch of not-quite-white snow continues to cling insolently to the ground, and when we drove up to Connecticut last Sunday and saw snowflakes on the windshield of our car as we passed through Hartford, I briefly felt like crying.

The very next morning, though, I saw a crocus poking through the blanket of long-dead leaves that cover our front lawn. I had to forcibly restrain myself from waking Mrs. T up to tell her about it. I didn’t know about crocuses other than in theory before I met my wife, and even then it’s been rare for me to see the ones that she gleefully spies on our lawn each April. It’s customary for me to spend the whole of that month not in Connecticut but New York, covering the overwhelming crush of plays and musicals that open at the very end of the theater season. Hence I usually learn of the arrival of the crocuses of spring not at first hand but on the phone.

To actually see one for myself was not merely a treat but downright therapeutic. Never before have I survived a winter that tested my equanimity so severely. By the end of it, I was wondering whether I had finally reached the time of life when I might need to give serious thought to living somewhere other than New York, not just for a month or two each year but permanently. I was downright desperate for sunlight and warmth.

To actually see one for myself was not merely a treat but downright therapeutic. Never before have I survived a winter that tested my equanimity so severely. By the end of it, I was wondering whether I had finally reached the time of life when I might need to give serious thought to living somewhere other than New York, not just for a month or two each year but permanently. I was downright desperate for sunlight and warmth.

While the latter has not yet come, there was a fair amount of sunshine to be seen this weekend, and I feel confident that the last bits of snow in our yard will have melted away by the time I go back to Connecticut. No doubt I’ll be complaining shortly thereafter about the cruelty of summer—but when I do, I hope I’ll remember to laugh.

Few human beings, even those who are, like me, inclined to a comfortable evenness of temperament, are capable of enjoying things as they are for very long. We are, it seems, destined to be dissatisfied, and I share as fully as the rest of us in the common dilemma. Indeed, our inability to remember past suffering with any degree of specificity is very likely the only thing that keeps us going. I shall, however, try to recall the winter of 2015 at best as I can for as long as I can, and cling to at least a few shreds of the abject gratitude that I felt when I caught sight of the first crocus of spring.

* * *

The opening of Benjamin Britten’s Spring Symphony, performed by the chorus and orchestra of the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, conducted by the composer:

| M | T | W | T | F | S | S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | ||||

| 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

| 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 |

| 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 |

| 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 | |

An ArtsJournal Blog