“A man is never so on trial as in the moment of excessive good fortune.”

“A man is never so on trial as in the moment of excessive good fortune.”

Lew Wallace, Ben-Hur: A Tale of the Christ

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City

My monthly essay for the June issue of Commentary, whose occasion is the publication of Molly Guptill Manning’s When Books Went to War: The Stories That Helped Us Win World War II , can now be read on line. Here’s an excerpt.

My monthly essay for the June issue of Commentary, whose occasion is the publication of Molly Guptill Manning’s When Books Went to War: The Stories That Helped Us Win World War II , can now be read on line. Here’s an excerpt.

* * *

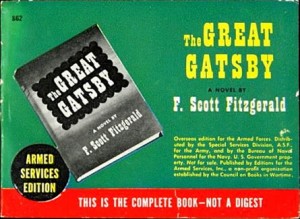

It’s said that two things about war are insufficiently appreciated by those who, like me, have not known it first-hand: 1) It is, when not terrifying, mostly dull, and 2) it is, like all human enterprises, subject to the operation of the law of unintended consequences. Few aspects of World War II better illustrate both of these points than the Armed Services Editions publishing project. Between 1943 and 1947, the U.S. Army and Navy distributed some 123 million newly printed paperback copies of 1,322 different books to American servicemen around the world. These volumes, which were given out for free, were specifically intended to entertain the soldiers and sailors to whom they were distributed, and by all accounts they did so spectacularly well. But they also transformed America’s literary culture in ways that their wartime publishers only partly foresaw—some of which continue to be felt, albeit in an attenuated fashion, to this day….

Starting from scratch, these civilians quickly managed to get large numbers of books into the hands of large numbers of grateful servicemen. Without their efforts, America’s soldiers and sailors would have found their wartime service to be even more cruelly burdensome than it was—and America’s authors and publishers would have faced a very different set of problems when the war ended and those servicemen returned home….

The story of the ASEs is told efficiently enough in When Books Went to War. But Manning is a lawyer, not a literary scholar, and she appears to have little or no awareness of their cultural context, thus making it impossible for her to interpret the project’s larger significance other than superficially. It is revealing, for instance, that the word “middlebrow” appears nowhere in When Books Went to War. Yet the most casual perusal of the list of books reprinted by the Council on Books in Wartime reveals that it reflected in every way the democratic assumptions of the middlebrow culture that dominated America throughout much of the 20th century. The vast popularity of the ASEs testifies to the strength of those assumptions.

The story of the ASEs is told efficiently enough in When Books Went to War. But Manning is a lawyer, not a literary scholar, and she appears to have little or no awareness of their cultural context, thus making it impossible for her to interpret the project’s larger significance other than superficially. It is revealing, for instance, that the word “middlebrow” appears nowhere in When Books Went to War. Yet the most casual perusal of the list of books reprinted by the Council on Books in Wartime reveals that it reflected in every way the democratic assumptions of the middlebrow culture that dominated America throughout much of the 20th century. The vast popularity of the ASEs testifies to the strength of those assumptions.

At the heart of middlebrow culture was the belief that high art was accessible to anyone who was willing to put in the effort to understand it, and that reading “serious” bestsellers such as Irving Stone’s Lust for Life or John P. Marquand’s The Late George Apley could serve as preparation for more ambitious ventures into great literature. For those servicemen who were already in the habit of reading for pleasure, the stateside counterpart of the ASEs was the Book-of-the-Month Club (which is mentioned only in passing in When Books Went to War). Both enterprises were essentially aspirational in their goals, both drew on the same wide-ranging pool of books, and both were broadly successful in elevating the literary tastes of those readers who made good use of them….

* * *

Read the whole thing here.

Here’s my list of recommended Broadway, off-Broadway, and out-of-town shows, updated weekly. In all cases, I gave these shows favorable reviews (if sometimes qualifiedly so) in The Wall Street Journal when they opened. For more information, click on the title.

BROADWAY:

• An American in Paris (musical, G, too complex for small children, virtually all performances sold out, reviewed here)

• Fun Home (serious musical, PG-13, all performances sold out, reviewed here)

• Hand to God (black comedy, X, absolutely not for children or prudish adults, some performances sold out, reviewed here)

• A Gentleman’s Guide to Love & Murder (musical, PG-13, reviewed here)

• The King and I (musical, G, perfect for children with well-developed attention spans, all performances sold out, reviewed here)

• Matilda (musical, G, nearly all performances sold out, reviewed here)

• Les Misérables (musical, G, too long and complicated for young children, reviewed here)

• On the Town (musical, G, contains double entendres that will not be intelligible to children, reviewed here)

• On the Twentieth Century (musical, G/PG-13, all performances sold out, closes July 19, contains very mild sexual content, reviewed here)

• The Visit (serious musical, PG-13, far too dark and disturbing for children, reviewed here)

OFF BROADWAY:

• Alfred Hitchcock’s The 39 Steps (comedy, G, ideal for bright children, remounting of Broadway production, original production reviewed here)

• The Fantasticks (musical, G, suitable for children capable of enjoying a love story, reviewed here)

CLOSING SOON IN CHICAGO:

CLOSING SOON IN CHICAGO:

• Sense and Sensibility (musical, G, closes June 14, reviewed here)

CLOSING NEXT WEEK ON BROADWAY:

• It’s Only a Play (comedy, PG-13/R, closes June 7, reviewed here)

CLOSING SUNDAY OFF BROADWAY:

• Grounded (drama, PG-13/R, explicit sexual references, reviewed here)

CLOSING SUNDAY IN CHICAGO:

• Side Man (drama, PG-13, reviewed here)

CLOSING SUNDAY IN MALVERN, PA.:

• Biloxi Blues (comedy, PG-13, sexual content, reviewed here)

Mrs. T and I have been catching up in recent weeks with a string of once-new films that slipped past us when they came out. On Wednesday we finally got around to Nebraska, which we both found deeply moving.

Mrs. T and I have been catching up in recent weeks with a string of once-new films that slipped past us when they came out. On Wednesday we finally got around to Nebraska, which we both found deeply moving.

It surprises me in retrospect that we didn’t make more of an effort to see Nebraska two years ago. Alexander Payne, after all, is one of the very few contemporary film directors who speaks for me. I know his world—I grew up in it—and his feeling for the parts of America that figure in his films is precise and perfect. (Likewise Mark Orton’s score for Nebraska, which is as beautifully plain and direct as the film itself.)

Part of what draws me to Payne’s work is that I have a special fondness for “satire” so close to literal representation as to be all but indistinguishable from it. That’s his specialty, and it’s what Nebraska is like. At times, in fact, it almost suggests a satirical version of The Trip to Bountiful. Yet just behind the comedy is an emotional affekt similar to that of Horton Foote’s masterpiece, whose simple but profound plot is undoubtedly echoed in Bob Nelson’s screenplay. Yes, Nebraska is funny—but all the laughter hurts.

Part of what draws me to Payne’s work is that I have a special fondness for “satire” so close to literal representation as to be all but indistinguishable from it. That’s his specialty, and it’s what Nebraska is like. At times, in fact, it almost suggests a satirical version of The Trip to Bountiful. Yet just behind the comedy is an emotional affekt similar to that of Horton Foote’s masterpiece, whose simple but profound plot is undoubtedly echoed in Bob Nelson’s screenplay. Yes, Nebraska is funny—but all the laughter hurts.

I reviewed Payne’s Election, About Schmidt, and Sideways in Crisis, and the second of those reviews also hints at the way I felt about Nebraska. Here it is, reprinted for the first time since it originally appeared in 2003.

* * *

In Hollywood, ordinary middle-class life is a state to be escaped, not examined. Unlike their novel-writing counterparts, American filmmakers are almost never willing to set a serious drama in a believable-looking small town (Kenneth Lonergan’s masterly You Can Count on Me was a rare exception) or even a medium-sized city anywhere other than on the East or West Coasts. To them, the vast expanse of terra incognita known in New York and Los Angeles as “flyover country” is little more than a breeding ground for cross-burners, serial murderers, and Republicans.

This iron law applies with particular force to the part of America where I was born and raised. It happens that I am writing this month’s column in a small midwestern town, the sort of place whose existence is all but unknown to most movie directors. As I unspooled a decade’s worth of memorable films in my head, I was hard-pressed to think of any that conveyed the slightest sense of what it looks and feels like to live in Red America. It’s revealing that the first ones to come to mind were Waiting for Guffman and Election, both of which are satires.

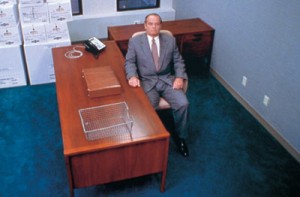

Now Alexander Payne, the director and cowriter (with Jim Taylor) of Election, has returned to Omaha, Nebraska, to make a very different sort of movie about life among the regular guys. To be sure, About Schmidt is also a satire, but its comic effects are much less broad than those of Election—indeed, you almost have to come from the Midwest to know that Payne and Taylor are exaggerating anything at all. Had Payne cast an actor other than Jack Nicholson, who is incapable of understatement, to play the part of Warren Schmidt, a superfluous middle manager whose tightly wrapped life unravels when he is nudged into the comfortable oblivion of retirement, it might well have been possible to take About Schmidt at something close to face value.

As it is, Nicholson does his best to keep from over-egging the pudding, but for all his palpably good intentions, I kept wishing that Payne had cast someone more like William H. Macy. But, then, you can’t make a big-budget movie without at least one big-budget star, and Nicholson is more than good enough to make About Schmidt much more than plausible. Even with Nicholson, it is one of the very best movies about which I have been lucky enough to write in this space.

Like Barbershop, another fine film that seeks to show the world as it is, About Schmidt doesn’t have much of a plot. Warren Schmidt is settling uneasily into a boring retirement when he comes home one day and finds his wife, Helen (June Squibb), dead on the floor of their kitchen. The shock of her death throws him into a depression from which he seeks to extract himself by driving from Omaha to Denver in his motor home, there to visit his soon-to-be-married daughter, Jeannie (Hope Davis, one of the best of the many fine actresses to come out of the indie-flick movement). Randall, Jeannie’s fiancé (Dermot Mulroney), is a long-haired waterbed salesman whose family never quite got over the Sixties. Jeannie loves him, but Schmidt loathes him, and the prospect of seeing his only child vanish into a mediocre marriage forces him to take an unsparing look at his own unsatisfying life.

Like Barbershop, another fine film that seeks to show the world as it is, About Schmidt doesn’t have much of a plot. Warren Schmidt is settling uneasily into a boring retirement when he comes home one day and finds his wife, Helen (June Squibb), dead on the floor of their kitchen. The shock of her death throws him into a depression from which he seeks to extract himself by driving from Omaha to Denver in his motor home, there to visit his soon-to-be-married daughter, Jeannie (Hope Davis, one of the best of the many fine actresses to come out of the indie-flick movement). Randall, Jeannie’s fiancé (Dermot Mulroney), is a long-haired waterbed salesman whose family never quite got over the Sixties. Jeannie loves him, but Schmidt loathes him, and the prospect of seeing his only child vanish into a mediocre marriage forces him to take an unsparing look at his own unsatisfying life.

One of the smartest things about Election was Alexander Payne’s refusal to let any of his characters off easy, even the ones with whom he might well have been expected to sympathize. Yes, Schmidt’s life has been emotionally constricted, but that didn’t make it altogether meaningless; yes, Randall and his family are more open to experience, but this openness has not made them better than Schmidt, just different. Most filmmakers make it agonizingly clear which side they’re on, but in About Schmidt as in Election before it, Payne casts a cold eye on all he sees. (It tells us everything we need to know about Randall, for instance, that he and Jeannie walk down the aisle to the insipid strains of Dan Fogelberg’s “Longer.”)

Interestingly enough, the only aspect of midwestern life about which About Schmidt has nothing interesting to say is religion. Warren Schmidt is experiencing a full-blown spiritual crisis, one whose seriousness is in no way diminished by his own smallness of soul, and it is surprising—to put it mildly that at no time in the course of the movie does he look to religion, organized or otherwise, as a possible source of enlightenment or solace. One could easily imagine his having been left in the lurch by the spiritual blandness of latter-day mainline Protestantism, in much the same way that Kenneth Lonergan skewers the sin-free Methodism of the clergyman he plays in You Can Count on Me. Yet in a film otherwise notable for its uncanny fidelity to fact, it is impossible to forget that a couple like Warren and Helen Schmidt would almost certainly have been fairly regular churchgoers in real life.

Time: near the end of a leisurely dinner. Place: Restaurant 15 Main, Narrowsburg, New York. Frank Sinatra’s recording of “Thanks for the Memory” is playing in the background.

SHE I never liked that song.

HE Well–

SHE Don’t say it–I already know what you’re going to say. “Well, I like it.” Of course you like it. You’re got more in common with your parents’ generation than with ours.

HE What do you mean? I know twice as much about rock and roll as you do.

SHE Yeah, but you never hung out in bars and danced with girls when you were in high school. …

Read the whole thing here.

| M | T | W | T | F | S | S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | ||||

| 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

| 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 |

| 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 |

| 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 | |

An ArtsJournal Blog