The Louvin Brothers sing “Hoping That You’re Hoping” on TV in 1956:

The Louvin Brothers sing “Hoping That You’re Hoping” on TV in 1956:

(This is the latest in a series of arts-related videos that appear in this space each Monday, Wednesday, and Friday.)

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City

In today’s Wall Street Journal I review a New Hampshire revival of A Garden Fête, one of the eight plays from Alan Ayckbourn’s Intimate Exchanges cycle, and the Lincoln Center Theater premiere of Douglas Carter Beane’s Shows for Days, which stars Patti LuPone. Here’s an excerpt.

* * *

Alan Ayckbourn’s “Intimate Exchanges,” first performed in 1983, consists of eight intertwined full-evening plays in which two actors portray a total of ten characters. The plays all start in the same way, then shear off in different directions—and each one is equipped with its own pair of alternate endings. While the complete cycle can only be presented in a festival setting, all of the plays are free-standing and can also be produced independently, and the Peterborough Players, who mounted a first-class revival of Mr. Ayckbourn’s “Absurd Person Singular” in 2013, are now doing “A Garden Fête,” inviting the members of the audience to vote on which ending will be performed.

Alan Ayckbourn’s “Intimate Exchanges,” first performed in 1983, consists of eight intertwined full-evening plays in which two actors portray a total of ten characters. The plays all start in the same way, then shear off in different directions—and each one is equipped with its own pair of alternate endings. While the complete cycle can only be presented in a festival setting, all of the plays are free-standing and can also be produced independently, and the Peterborough Players, who mounted a first-class revival of Mr. Ayckbourn’s “Absurd Person Singular” in 2013, are now doing “A Garden Fête,” inviting the members of the audience to vote on which ending will be performed.

I had the good fortune to see Mr. Ayckbourn’s own stagings of the eight “Intimate Exchanges” plays performed off Broadway in 2008 by two members of his own Stephen Joseph Theatre, Bill Champion and Claudia Elmhirst. Nobody stages Mr. Ayckbourn’s work better than the playwright himself, but Gus Kaikkonen, Peterborough’s artistic director, comes very close, for he understands that “A Garden Fête,” like its seven companion pieces, is a dead-serious farce whose unfailingly uproarious horseplay cloaks a piercing vision of the limitations of human love. As always with Mr. Ayckbourn, the results are really, really funny, but the best jokes (if you want to call them that) are all double-edged and shiv-sharp, especially the ones that have to do with marriage…

Many people who wind up devoting their lives to theater get their start in one of the countless small-town amateur troupes known as “community theaters.” Some are as absurdly awful as the one that is satirized on screen in “Waiting for Guffman,” while others are near-professional in quality. Most probably fall somewhere in between these two extremes. Douglas Carter Beane, who spent his teenage years acting with such a group, has now written a lightweight but charming autobiographical comedy—call it a memory farce—about what it’s like to do Shaw on a shoestring. While “Shows for Days” is no masterpiece, it’s unfailingly funny and disarmingly sweet, and if you’ve ever had anything to do with amateur theater, it will fill you with memories of the way you were once upon a time….

Many people who wind up devoting their lives to theater get their start in one of the countless small-town amateur troupes known as “community theaters.” Some are as absurdly awful as the one that is satirized on screen in “Waiting for Guffman,” while others are near-professional in quality. Most probably fall somewhere in between these two extremes. Douglas Carter Beane, who spent his teenage years acting with such a group, has now written a lightweight but charming autobiographical comedy—call it a memory farce—about what it’s like to do Shaw on a shoestring. While “Shows for Days” is no masterpiece, it’s unfailingly funny and disarmingly sweet, and if you’ve ever had anything to do with amateur theater, it will fill you with memories of the way you were once upon a time….

“Shows for Days” has a loosely knit, Kleenex-thin plot that makes an unconvincing swerve into melodrama after intermission. But the six actors, Ms. LuPone above all, squeeze every drop of comic juice from their campy zingers…

* * *

To read my review of A Garden Fête, go here.

To read my review of Shows for Days, go here.

And what color should he be? That’s the subject, more or less, of my “Sightings” column in today’s Wall Street Journal. Here’s an excerpt.

* * *

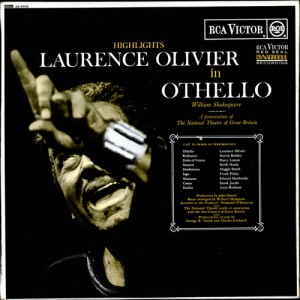

In this country, Steven Berkoff is mostly known (if at all) as the villain in “Beverly Hills Cop.” In his native England, by contrast, he is known as an avant-garde theater artist who likes to say outrageous things. It was in the latter capacity that he recently went after a London drama critic, Paul Taylor of the Independent, who was covering the Royal Shakespeare Company’s new production of “Othello,” in which the title role, as is now the invariable custom, was played by a black actor, Hugh Quarshie. “The days when it was thought acceptable for a white actor to black up as Othello are well behind us,” Mr. Taylor wrote. Mr. Berkoff responded angrily on his Facebook page by recalling Laurence Olivier’s performance in “Othello”: “I was so lucky I was able to witness this great event before the fiends of political correctness in all their self-righteousness had struck a no-go-zone for white actors on that particular role.”

Anyone who’s seen Olivier’s Othello, which was filmed in 1965, knows that it was, indeed, a supremely great event. But anyone who follows the theater scene knows that such an event will never happen again, at least not in my lifetime. Today we take it for granted that Othello, one of the only two major Shakespearean characters who is specifically described by the playwright as black, should be played by a black actor. It’s considered inappropriate, even racist, for a white actor to put on blackface, as Olivier did 50 years ago, to play Othello.

Anyone who’s seen Olivier’s Othello, which was filmed in 1965, knows that it was, indeed, a supremely great event. But anyone who follows the theater scene knows that such an event will never happen again, at least not in my lifetime. Today we take it for granted that Othello, one of the only two major Shakespearean characters who is specifically described by the playwright as black, should be played by a black actor. It’s considered inappropriate, even racist, for a white actor to put on blackface, as Olivier did 50 years ago, to play Othello.

And should that be so? Well…it’s complicated.

Nowadays virtually all theater companies are committed, some more zealously than others, to what’s known as “non-traditional casting,” which is very often employed without regard for strict dramatic or visual logic….

So why not a white Othello? Wouldn’t that qualify as non-traditional these days? The answer is obvious: The door of non-traditional casting swings one way. It is normally intended to benefit minorities, not whites, who have no history of being excluded from stage roles because of their skin color. To be sure, I can easily imagine an “Othello” in which all of the characters but Othello were black, and I expect that would pass political muster. Nothing less, however, would be deemed acceptable today…

Is that logical? I suppose not. But America, as the multifarious complexities of the Rachel Dolezal imbroglio remind us, has never been very logical when it comes to matters of race….

* * *

Read the whole thing here.

An excerpt from the 1965 film of Othello, directed by Stuart Burge, with Laurence Olivier in the title role and Maggie Smith as Desdemona. The film is closely based on John Dexter’s 1964 National Theatre staging of the play:

An excerpt from Abe Lincoln in Illinois, starring Raymond Massey as Abraham Lincoln. The film, released in 1940, was directed by John Cromwell and adapted by Robert E. Sherwood from his original stage play, which opened on Broadway in 1938 and ran for 472 performances. This scene is a fictionalized portrayal of one of the Lincoln-Douglas debates. Stephen Douglas is played by Gene Lockhart:

An excerpt from Abe Lincoln in Illinois, starring Raymond Massey as Abraham Lincoln. The film, released in 1940, was directed by John Cromwell and adapted by Robert E. Sherwood from his original stage play, which opened on Broadway in 1938 and ran for 472 performances. This scene is a fictionalized portrayal of one of the Lincoln-Douglas debates. Stephen Douglas is played by Gene Lockhart:

(This is the latest in a series of arts-related videos that appear in this space each Monday, Wednesday, and Friday.)

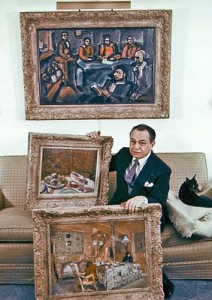

I’ve been reading All My Yesterdays, Edward G. Robinson’s posthumously published 1973 autobiography. Contrary to his celebrated tough-guy screen persona, Robinson was an exceedingly literate and cultivated man, a regular concertgoer and one of golden-age Hollywood’s leading art collectors. He was also a very liberal Democrat who, though never a Communist, was far enough to the left to make it into the pages of Red Channels. Hence I was more than a little bit surprised to run across the following passage in his book:

I’ve been reading All My Yesterdays, Edward G. Robinson’s posthumously published 1973 autobiography. Contrary to his celebrated tough-guy screen persona, Robinson was an exceedingly literate and cultivated man, a regular concertgoer and one of golden-age Hollywood’s leading art collectors. He was also a very liberal Democrat who, though never a Communist, was far enough to the left to make it into the pages of Red Channels. Hence I was more than a little bit surprised to run across the following passage in his book:

There is a magazine called The National Review edited by William Buckley, whom I have never met. I disagree with almost everything Mr. Buckley writes, and I know why I disagree. We come from different worlds; we can look at the same object or set of facts, and we will both, quite honestly, arrive at different conclusions. However, since I’ve never written a letter to him, this is the first he will know of it—even disagreeing, as I do, I love to read him. In the first place, I believe he believes what he’s saying; and, indeed, he has something to say that needs saying even though I’m diametrically opposed; and, finally, he writes like a dream. What he does with the English language is pure joy.

I wonder whether Bill ever read this paragraph from All My Yesterdays, or heard about it. For my part, I found it to be a touching reminder that there was once a time when it seems to have been easier for public figures on opposite sides of the ideological fence to express mutual admiration. Bill himself was very good at it, as Kevin M. Schultz reminds us in a newly published book about his longstanding friendship with Norman Mailer. Both men genuinely appreciated each other’s talents, and said so for quotation—often.

What happened to those days? Could it be that the political stakes are higher now than they were in 1973? (It certainly didn’t feel that way back then.) Or is civility itself in the process of vanishing, not just from the political arena but from American culture as a whole? I can’t say. I merely offer Robinson’s thoughts for you to ponder.

* * *

Edward G. Robinson appears as the mystery guest on the December 16, 1962 episode of What’s My Line? John Daly is the host and the panelists are Bennett Cerf, Arlene Francis, Dorothy Kilgallen, and Steve Lawrence:

“It has been frequently remarked, that it seems to have been reserved to the people of this country to decide, by their conduct and example, the important question, whether societies of men are really capable or not, of establishing good government from reflection and choice, or whether they are forever destined to depend, for their political constitutions, on accident and force.”

“It has been frequently remarked, that it seems to have been reserved to the people of this country to decide, by their conduct and example, the important question, whether societies of men are really capable or not, of establishing good government from reflection and choice, or whether they are forever destined to depend, for their political constitutions, on accident and force.”

Alexander Hamilton, The Federalist No. 1 (Oct. 27, 1787)

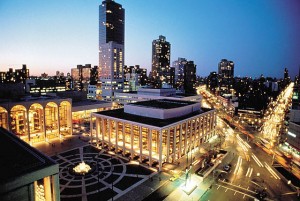

My essay in the July/August double issue of Commentary is about Lincoln Center. Here’s an excerpt.

* * *

Lincoln Center, the first major urban performing-arts center in America, was well on its way to completion a half-century ago. The New York City Ballet, the New York City Opera, and the New York Philharmonic had already moved there, and the Metropolitan Opera followed suit in 1966. Theatrical productions began to be mounted in the Vivian Beaumont Theater by the end of 1965, and the Juilliard School and the School of American Ballet relocated to its 16-acre campus a few years later. This unprecedented consolidation remains to this day unrivaled in scope: No other performing-arts center dominates the artistic life of a great American city so totally.

In recent years, though, Lincoln Center has weathered an equally unprecedented series of crises. The New York City Opera stopped performing there in 2011 and closed its doors two years later. Shortly thereafter, the Metropolitan Opera was forced to contend with a fiscal meltdown that threatens its very survival. Meanwhile, the New York Philharmonic, whose concert hall is closing in 2019 for desperately needed interior renovations, announced that Alan Gilbert, its music director, will be stepping down from that post in 2017 after a tenure widely regarded as lackluster….

In recent years, though, Lincoln Center has weathered an equally unprecedented series of crises. The New York City Opera stopped performing there in 2011 and closed its doors two years later. Shortly thereafter, the Metropolitan Opera was forced to contend with a fiscal meltdown that threatens its very survival. Meanwhile, the New York Philharmonic, whose concert hall is closing in 2019 for desperately needed interior renovations, announced that Alan Gilbert, its music director, will be stepping down from that post in 2017 after a tenure widely regarded as lackluster….

Hence it is unusually timely that Reynold Levy, who served as Lincoln Center’s president from 2002 to 2014, has published a memoir noteworthy both for its candor and its smugness. As its title suggests, They Told Me Not to Take That Job: Tumult, Betrayal, Heroics, and the Transformation of Lincoln Center is even more self-serving than most books of its genre. Levy all too clearly sees himself as the heroic figure who single-handedly wrought “transformational change” in the face of “seemingly intractable problems,” and he believes that most of Lincoln Center’s remaining difficulties are the result of certain of its constituents having stubbornly refused to take his advice….

Levy’s indictments are plausible as far as they go. They ignore, however, the fact that Lincoln Center’s original designers made irreversible miscalculations whose long-term consequences are now glaringly apparent and increasingly dire….

In the end, Lincoln Center is best understood as a historical accident, one that has had a distorting and destructive effect on the performing arts elsewhere in America….

* * *

Read the whole thing here.

| M | T | W | T | F | S | S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | ||||

| 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

| 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 |

| 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 |

| 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 | |

An ArtsJournal Blog