(1) The computer is the worst enemy of a workaholic with a chest cold.

(2) The iPod is his best friend (especially if he sleeps in a loft).

(3) Don’t watch Red Rock West when you have a fever….

Read the whole thing here.

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City

(1) The computer is the worst enemy of a workaholic with a chest cold.

(2) The iPod is his best friend (especially if he sleeps in a loft).

(3) Don’t watch Red Rock West when you have a fever….

Read the whole thing here.

It seems miraculously, even magically appropriate that I should be able to listen to Constant Lambert’s 1937 recording of Peter Warlock’s String Serenade on my iPod, as I did a few weeks ago, while simultaneously reading about Hugh Moreland, my favorite character in A Dance to the Music of Time, Anthony Powell’s twelve-volume roman fleuve about life in England before, during, and after World War II.

It seems miraculously, even magically appropriate that I should be able to listen to Constant Lambert’s 1937 recording of Peter Warlock’s String Serenade on my iPod, as I did a few weeks ago, while simultaneously reading about Hugh Moreland, my favorite character in A Dance to the Music of Time, Anthony Powell’s twelve-volume roman fleuve about life in England before, during, and after World War II.

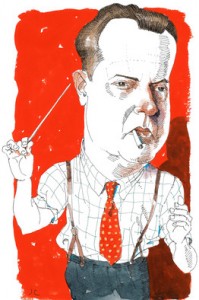

As longtime readers of this blog know, Moreland was Powell’s fictionalized version of Lambert, to whom he was very close. All who knew Lambert agreed that his portrait in Dance was both evocative and convincing. Powell knew Warlock, too, if less intimately, and portrayed him as “Maclintick” in Dance. His real name was Philip Heseltine—Peter Warlock was his professional pseudonym—and Powell’s reminiscences of the man himself ring no less true:

As longtime readers of this blog know, Moreland was Powell’s fictionalized version of Lambert, to whom he was very close. All who knew Lambert agreed that his portrait in Dance was both evocative and convincing. Powell knew Warlock, too, if less intimately, and portrayed him as “Maclintick” in Dance. His real name was Philip Heseltine—Peter Warlock was his professional pseudonym—and Powell’s reminiscences of the man himself ring no less true:

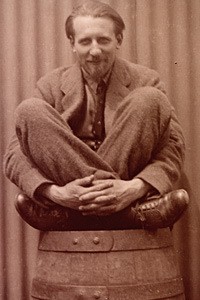

[He] had by taking thought turned himself into a consciously mephistophelian figure, an appearance assisted by a pointed fair beard and light-coloured eyes that were peculiarly compelling….I always found him agreeable and highly entertaining; though never without a sense, as with many persons of at times malignant temper, that things might suddenly go badly wrong.

Call him what you will, Heseltine/Warlock was a minor master whose strong style is immediately recognizable. Among the best and most fully realized of his works is the String Serenade, composed in 1922 and dedicated “to Frederick Delius on his sixtieth birthday.” It’s a six-minute dance movement, a melancholy, gently swaying minor-key “siciliano” in six-eight time. Delius heard it on the radio in 1926 and sent Warlock a warm note claiming to be “charmed with its musical sensibility and coloured atmosphere!”

Call him what you will, Heseltine/Warlock was a minor master whose strong style is immediately recognizable. Among the best and most fully realized of his works is the String Serenade, composed in 1922 and dedicated “to Frederick Delius on his sixtieth birthday.” It’s a six-minute dance movement, a melancholy, gently swaying minor-key “siciliano” in six-eight time. Delius heard it on the radio in 1926 and sent Warlock a warm note claiming to be “charmed with its musical sensibility and coloured atmosphere!”

Lambert was just as fond of the siciliano, which turns up repeatedly in his own compositions, and it isn’t hard to figure out why he interpreted this particular specimen so sympathetically in his parallel life as an orchestral conductor. Like Warlock, he was much given to melancholy (“Moreland’s face in repose, in spite of this cherubic, humorous character, was not without melancholy too”) and, for all his high spirits and flashing wit, never seemed quite at home in the world. He died of drink, more or less, in 1951. It was a sad and unsuitable end, though not nearly so sad as that of Warlock, who gassed himself, having first put out his cat.

I love the music of both men passionately, and it’s surprising that I’d never before had occasion to listen to any of it while reading about them in A Dance to the Music of Time, seeing as how I’m a similarly ardent admirer of Powell’s writing. For modern technology facilitates such exercises in aesthetic serendipity, and all it took for me to bring these three long-dead friends together again was a few quick clicks on my laptop. I wonder, though, what they would have thought of being summoned from the shades in such a way. Would they have seen the electronic wizardry of the twenty-first century as a mortal threat to art?

Consider, for example, the first sentence of this post, in which I pay implicit and reflexive homage to the shiny new god that we call “multitasking.” But is it really so magical and miraculous as all that? To read a book or listen to music on a computer, after all, is to be no more than a keystroke away from distraction, which is the enemy of the intense, focused concentration that those who love art once cultivated as a matter of course. Do I really profit from being able to listen to Warlock’s music conducted by Lambert while simultaneously reading what Powell wrote about both men’s personalities—or am I watering down all three experiences, in something of the same way that so many postmodern museumgoers water down the immediate experience of looking at great paintings by simultaneously listening to recorded lectures about their greatness?

Consider, for example, the first sentence of this post, in which I pay implicit and reflexive homage to the shiny new god that we call “multitasking.” But is it really so magical and miraculous as all that? To read a book or listen to music on a computer, after all, is to be no more than a keystroke away from distraction, which is the enemy of the intense, focused concentration that those who love art once cultivated as a matter of course. Do I really profit from being able to listen to Warlock’s music conducted by Lambert while simultaneously reading what Powell wrote about both men’s personalities—or am I watering down all three experiences, in something of the same way that so many postmodern museumgoers water down the immediate experience of looking at great paintings by simultaneously listening to recorded lectures about their greatness?

No doubt all this is but one of the countless aspects of the inseparably mixed blessing that is progress. In exchange for the boon of instant access to art of all kinds, my generation of aesthetes now lives under the ever-present aspect of instant distraction from its consoling beauties. In the end, this access may prove to have been a devil’s deal—for which reason the man who chose to call himself Peter Warlock might well have taken a macabre kind of pleasure in it.

* * *

Constant Lambert conducts Peter Warlock’s Serenade for Strings:

To hear Anthony Powell talk about Lambert in his 1976 appearance on the BBC’s Desert Island Discs, go here.

Harold Arlen sings and plays a medley of his songs on The Colgate Comedy Hour, assisted by Eddie Cantor, Connie Russell, and Frank Sinatra. This episode was originally telecast on November 29, 1953:

Harold Arlen sings and plays a medley of his songs on The Colgate Comedy Hour, assisted by Eddie Cantor, Connie Russell, and Frank Sinatra. This episode was originally telecast on November 29, 1953:

(This is the latest in a series of arts-related videos that appear in this space each Monday, Wednesday, and Friday.)

In today’s Wall Street Journal drama column I report from Wisconsin on American Players Theatre’s productions of An Iliad, The Island, and The Merry Wives of Windsor. Here’s an excerpt.

* * *

America has no finer classical actor than Jim DeVita, a 21-year veteran of Wisconsin’s American Players Theatre. In recent seasons he’s starred there in “Antony and Cleopatra,” “The Critic,” “Long Day’s Journey into Night,” “Macbeth” and “The Seagull,” and the disciplined intensity of his performances in those widely varied roles has never failed to impress. This year, though, Mr. DeVita is outdoing himself in “An Iliad,” the 2012 Lisa Peterson-Denis O’Hare monodrama that uses Robert Fagles’ translation of Homer’s epic poem as the starting point for a colloquial recounting of the Trojan War myth. It’s a dream part for a first-class actor, and to say that Mr. DeVita fills the bill is to understate the case by several orders of magnitude.

Working hand in hand with John Langs, the director, Mr. DeVita has made over the unnamed “poet” of “An Iliad” into an eccentric, hard-drinking teacher whose mission is to use Homer’s poem to teach his students how war has the malign power to seduce men…

Working hand in hand with John Langs, the director, Mr. DeVita has made over the unnamed “poet” of “An Iliad” into an eccentric, hard-drinking teacher whose mission is to use Homer’s poem to teach his students how war has the malign power to seduce men…

The manic, near-demented ferocity of Mr. DeVita’s acting—think Robin Williams as a classics professor—is so all-consuming as to suggest that you’re not witnessing a theatrical event but taking part in a real-life experience….

“An Iliad” is being performed in APT’s 201-seat Touchstone Theatre, a thrust-stage house of unrivaled intimacy that is no less well suited to Derrick Sanders’ revival of “The Island,” the famous 1973 play in which Athol Fugard, writing in partnership with the actors John Kani and Winston Ntshona, puts you inside a chokingly tiny cell on Robben Island, the site of one of South Africa’s most notorious apartheid-era prisons for political dissidents…

Yes, the play is nominally “about” apartheid, but its real subject is the transformative power of art and friendship, and LaShawn Banks and Chiké Johnson, who play the prisoners, are so far inside their parts that the word “realism” fails altogether to suggest the truth of their performances…

Should you feel the understandable need for a chaser after seeing “An Iliad” or “The Island,” I recommend that you climb the hill to the company’s 1,147-seat outdoor amphitheatre to see Tim Ocel’s version of “The Merry Wives of Windsor,” a warmly genial staging in which every line is enunciated with clarity and common sense….

Brian Mani, who proved his uproarious mettle as a stage comedian in APT’s productions of George Bernard Shaw’s “Widowers’ Houses” and Somerset Maugham’s “The Circle,” here gives us a W.C. Fields-like Falstaff who oozes utter fraudulence from every pore…

* * *

To read my reviews of An Iliad and The Island, go here.

To read my review of The Merry Wives of Windsor, go here.

In today’s Wall Street Journal “Sightings” column I reflect on a near-unknown pop record that could have changed the course of the Broadway musical had it been commercially released. Here’s an excerpt.

In today’s Wall Street Journal “Sightings” column I reflect on a near-unknown pop record that could have changed the course of the Broadway musical had it been commercially released. Here’s an excerpt.

* * *

What went wrong with the Broadway musical? It used to be one of the main sources of creative vitality in American music, but now it’s a stylistic backwater. Why? I can tell you in two sentences. Fifty years ago this week, the number-one single on Billboard’s Hot 100 chart was the Rolling Stones’ “(I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction.” And what were the hottest musicals on Broadway? “Fiddler on the Roof” and “Hello, Dolly!”

Pop music and the Broadway musical were already veering off in opposite directions when the Stones and the Beatles first laid siege to the top of the charts in 1964. A year later, the chasm that separated them appeared to have become unbridgeable. A handful of shows later in the ‘60s, including “Hair” and “Promises, Promises,” sought to narrow that fast-growing gap, but they promised more in the way of musical substance than they delivered. Not until Lin-Manuel Miranda’s “Hamilton,” which opens on Broadway next Thursday, would there be a hit musical with a first-rate score that was (as I said in my review of the off-Broadway production) “plugged straight into the wall socket of contemporary music.” For the most part, the Broadway songwriters of the ‘60s and ‘70s deliberately ignored rock, R&B and the other musical idioms to which the baby boomers were listening, and by the time they finally got around to changing their minds, it was too late to bring younger listeners on board.

Did it have to be that way? Probably, but not necessarily—and the man who might have nudged Broadway in a different direction was Stephen Sondheim.

Did it have to be that way? Probably, but not necessarily—and the man who might have nudged Broadway in a different direction was Stephen Sondheim.

To be sure, Mr. Sondheim is on the face of it a thoroughly unlikely suspect. He admitted in 1988 that he’s “not interested in rock or pop because I wasn’t brought up with it,” later claiming that “attempting to blend contemporary pop music with theater music…doesn’t work very well.” Maybe he’s right. But in 1969, Harry Nilsson, one of the most imaginative popular singer-songwriters of his day, cut a remarkable record of a Sondheim ballad called “Marry Me a Little” that hinted at what might have been….

Arranged by George Tipton, Nilsson’s longtime collaborator, it’s an exquisitely crafted, gorgeously sung piece of late-‘60s pop whose multi-tracked vocals and richly layered yet clean-textured orchestral accompaniment are strikingly reminiscent of the Beatles’ “Abbey Road,” which had come out earlier that year….

* * *

Read the whole thing here.

Harry Nilsson’s 1969 recording of “Marry Me a Little”:

The Jimi Hendrix Experience is interviewed on the CBC. The other members of the group are Noel Redding on bass and Mitch Mitchell on drums. The interview was conducted by Terry David Mulligan in Vancouver on September 7, 1968:

The Jimi Hendrix Experience is interviewed on the CBC. The other members of the group are Noel Redding on bass and Mitch Mitchell on drums. The interview was conducted by Terry David Mulligan in Vancouver on September 7, 1968:

(This is the latest in a series of arts-related videos that appear in this space each Monday, Wednesday, and Friday.)

| M | T | W | T | F | S | S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | ||||

| 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

| 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 |

| 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 |

| 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 | |

An ArtsJournal Blog