Joni Mitchell sings “Night in the City” on the CBC in 1967:

Joni Mitchell sings “Night in the City” on the CBC in 1967:

(This is the latest in a series of arts-related videos that appear in this space each Monday, Wednesday, and Friday.)

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City

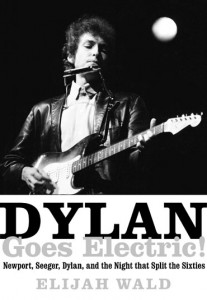

I’ve been reading Elijah Wald’s Dylan Goes Electric!: Newport, Seeger, Dylan, and the Night that Split the Sixties, which came out in July, with fascination and delight. Wald is one of the best pop-music historians we have, and his latest book is a little masterpiece, a fully comprehending portrait of a key moment of transition in postwar American culture, the night that Bob Dylan hauled an all-electric band onto the stage of the 1965 Newport Folk Festival and drove an axe into the center of popular music.

I’ve been reading Elijah Wald’s Dylan Goes Electric!: Newport, Seeger, Dylan, and the Night that Split the Sixties, which came out in July, with fascination and delight. Wald is one of the best pop-music historians we have, and his latest book is a little masterpiece, a fully comprehending portrait of a key moment of transition in postwar American culture, the night that Bob Dylan hauled an all-electric band onto the stage of the 1965 Newport Folk Festival and drove an axe into the center of popular music.

So Wald says, and he doesn’t exaggerate: Dylan’s decision to go electric was so consequential and controversial that an entire Wikipedia page has been devoted to it. Before he took the stage on July 25, 1965, the “folk revival” led by Pete Seeger was still a major force in commercial American pop. From that moment on, the heartfelt, homespun acoustic music of Seeger, Joan Baez, and their socially conscious peers—among whom Dylan had once been numbered—was yesterday’s news. Rock became the lingua franca of American popular music, and remained so until the triumph of hip-hop three decades later.

This radical transformation happened unbeknownst to me. I’d listened to music of sundry kinds throughout my childhood, but I discovered it—all of it—in 1968, the year I turned twelve. Prior to that time, my knowledge of what it sounded like was mostly limited to my father’s record collection, which consisted in the main of swing and jazz albums and pop singles from the Fifties, augmented by what I saw and heard on TV. Smalltown, U.S.A., had only two AM radio stations, neither of which was hip by any conceivable standard. They played the Top 40, and the best-selling singles of 1967, according to Billboard, were, in descending order, Lulu’s “To Sir With Love,” the Box Tops’ “The Letter,” Bobbie Gentry’s “Ode to Billie Joe,” the Association’s “Windy,” and the Monkees’ “I’m a Believer.”

Yes, there were more galvanizing sounds to be found on the airwaves. Billboard’s Hot 100 for 1967 also included, among other things, the Beatles’ “All You Need Is Love,” James Brown’s “Cold Sweat,” Buffalo Springfield’s “For What It’s Worth,” Aretha Franklin’s “Respect,” the Jefferson Airplane’s “Somebody to Love,” the Rolling Stones’ “Ruby Tuesday,” Sam & Dave’s “Soul Man,” and the Spencer Davis Group’s “Gimme Some Lovin.’” But I don’t remember hearing any of them that year, at least not on the radio. The hits of 1967 that I recall most clearly, if not nostalgically, are (I blush to admit it) “Incense and Peppermints” and “Snoopy Vs. the Red Baron.” What can I say? I was eleven and still in a state of unkissed innocence.

All that began to change when I took up the violin in the fall of 1967 and, a year later, fell into the clutches of Bob Nelson, a bearded social-studies teacher who took it upon himself to force my ears open by loaning me a stack of albums from his personal collection, including Baez’ Any Day Now, the Beatles’ White Album, Judy Collins’ In My Life, Dylan’s John Wesley Harding, the Firesign Theatre’s How Can You Be in Two Places at Once When You’re Not Anywhere at All (which I once thought incredibly funny and now find unendurable), and Arlo Guthrie’s Alice’s Restaurant (the title track of which I immediately memorized). At the same time I checked countless classical albums out of the public library—my favorites were Horowitz in Concert and Eugene Ormandy’s version of Aaron Copland’s Appalachian Spring—and started digging into my father’s jazz albums, of which Dave Brubeck’s Jazz Goes to College and Duke Ellington’s In a Mellotone made the most lasting impressions.

All that began to change when I took up the violin in the fall of 1967 and, a year later, fell into the clutches of Bob Nelson, a bearded social-studies teacher who took it upon himself to force my ears open by loaning me a stack of albums from his personal collection, including Baez’ Any Day Now, the Beatles’ White Album, Judy Collins’ In My Life, Dylan’s John Wesley Harding, the Firesign Theatre’s How Can You Be in Two Places at Once When You’re Not Anywhere at All (which I once thought incredibly funny and now find unendurable), and Arlo Guthrie’s Alice’s Restaurant (the title track of which I immediately memorized). At the same time I checked countless classical albums out of the public library—my favorites were Horowitz in Concert and Eugene Ormandy’s version of Aaron Copland’s Appalachian Spring—and started digging into my father’s jazz albums, of which Dave Brubeck’s Jazz Goes to College and Duke Ellington’s In a Mellotone made the most lasting impressions.

Then, in the summer of 1970, I sweet-talked Richard Powell, my junior-high music teacher, into letting me borrow a plywood bass from the band room for the summer. I’d decided that it might be fun to teach myself how to play along with the records to which I was listening, and I suspected, not unreasonably, that it would be easier to do so on bass than on violin. Soon thereafter my long-suffering parents bought me a twelve-string guitar, a piano, and—most fatefully—a Fender bass and amplifier. From then on and for many years to come, music was the main source of meaning in my life.

What is most revealing about my near-total immersion in music is that it seems never to have occurred to me to limit myself to a particular genre. Instead I discovered it in an explosion of simultaneity: I listened to classical music, rock, and jazz with identical closeness. Not long afterward I played one of the leads in in a community-theater musical, bought a copy of Elektra’s four-disc Folk Box, and joined a country band. That Christmas my Aunt Suzy gave me a subscription to Stereo Review, whose eclectic critics (one of whom, Chris Albertson, now follows me on Facebook, much to my secret delight) ranged even more widely afield, and before long I’d added Mabel Mercer and Bobby Short to my bizarrely eclectic playlist.

To be a teenage boy, however, is to long above all things to appreciate the music of your own time. For me that was rock and roll, and notwithstanding the unhelpfulness of the local radio stations, there were plenty of other ways to learn about it, including Looney Tunes & Merrie Melodies, one of the “Loss Leader” samplers that Warner Bros. sold by mail for a dollar a disc. I saw an ad for Looney Tunes & Merrie Melodies in Stereo Review in 1971, sent off three crumpled one-dollar bills ($17 today), and a few weeks later found myself in possession of a three-LP box set containing thirty-three songs by the very wide-ranging likes of Black Sabbath, Captain Beefheart, Ry Cooder, the Faces, Fleetwood Mac, Jimi Hendrix, Gordon Lightfoot, the Grateful Dead, the Kinks, Little Feat, Little Richard, Van Morrison, Randy Newman, Van Dyke Parks, James Taylor, Jimmy Webb, the Youngbloods, Frank Zappa and the Mothers of Invention, and a British group called, believe it or not, Hard Meat. (They were actually pretty good.) Some I loved, some I loathed, a few I didn’t quite get, but none of it mattered: I soaked them all up with indiscriminate avidity.

To be a teenage boy, however, is to long above all things to appreciate the music of your own time. For me that was rock and roll, and notwithstanding the unhelpfulness of the local radio stations, there were plenty of other ways to learn about it, including Looney Tunes & Merrie Melodies, one of the “Loss Leader” samplers that Warner Bros. sold by mail for a dollar a disc. I saw an ad for Looney Tunes & Merrie Melodies in Stereo Review in 1971, sent off three crumpled one-dollar bills ($17 today), and a few weeks later found myself in possession of a three-LP box set containing thirty-three songs by the very wide-ranging likes of Black Sabbath, Captain Beefheart, Ry Cooder, the Faces, Fleetwood Mac, Jimi Hendrix, Gordon Lightfoot, the Grateful Dead, the Kinks, Little Feat, Little Richard, Van Morrison, Randy Newman, Van Dyke Parks, James Taylor, Jimmy Webb, the Youngbloods, Frank Zappa and the Mothers of Invention, and a British group called, believe it or not, Hard Meat. (They were actually pretty good.) Some I loved, some I loathed, a few I didn’t quite get, but none of it mattered: I soaked them all up with indiscriminate avidity.

In addition, certain variety shows of that era were known for booking rock acts. I came along a bit too late to catch the Beatles and the Rolling Stones on The Ed Sullivan Show, but I did watch the Who blow up their instruments after singing “My Generation” on The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour in 1967, an event whose mad extravagance knocked me flat. No budget-conscious small-town boy whose parents were buying him a Roth student-model violin on the installment plan could have been anything other than stupefied to see Pete Townshend smashing his guitar to pieces on network TV.

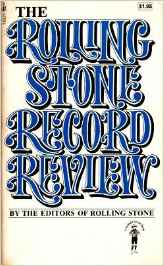

At length I turned for counsel to The Rolling Stone Record Review, a paperback anthology of pieces from Rolling Stone originally published in 1971. Some of the reviews reprinted therein were so strikingly written that I can still quote them, and I studied my dog-eared copy until the pages fluttered loose. It was my Bible of hipness, a vade mecum of all that was most serious about rock, and it was a long time before I dared to break away from its seemingly apodictic judgments and start trusting my own ears.

At length I turned for counsel to The Rolling Stone Record Review, a paperback anthology of pieces from Rolling Stone originally published in 1971. Some of the reviews reprinted therein were so strikingly written that I can still quote them, and I studied my dog-eared copy until the pages fluttered loose. It was my Bible of hipness, a vade mecum of all that was most serious about rock, and it was a long time before I dared to break away from its seemingly apodictic judgments and start trusting my own ears.

I’m surprised in retrospect that Bob Dylan didn’t make a deeper mark on me back then, but it wasn’t until after I became an adult that I grasped his significance. He was, as Donald Fagen has rightly said, the most influential songwriter of his time: “Before Bob, no one in the pop medium had ever used that breadth of subject matter or surrealistic and dream language.” Perhaps I simply found him too late: the bomb had already gone off. By 1968 everybody was loud, and all of the best songwriters had long since learned Dylan’s elliptical lessons. And because I approached rock both as an eager listener and as a budding young executant who put a premium on vocal and instrumental polish, his rough-hewn style didn’t speak to me.

Of course I knew how good his songs were, but I mostly preferred other people’s cover versions, and in some cases still do: Hendrix’ “All Along the Watchtower,” Johnny Winter’s “Highway 61 Revisited,” the Byrds’ “It’s All Over Now, Baby Blue,” Joan Baez’ “Love Minus Zero/No Limit,” the Band’s “This Wheel’s on Fire.” Had Dylan recorded in the studio with the Band prior to 1974, I might well have felt differently—they were, and are, my favorite rock group after Steely Dan—but nobody in Smalltown, so far as I knew, owned a bootleg copy of The Basement Tapes, so I put him aside and sought revelation elsewhere.

Part of what I like about Dylan Goes Electric! is that it does such a good job of evoking the halcyon years on which I just missed out, the time when it still seemed that (in Wald’s words) “no matter how high Dylan’s records climbed on the pop charts, he was neither selling out nor buying in, but bravely going his own way.” You can’t read it without catching an echo of the excitement that he stirred up throughout the mid-Sixties, the same excitement that I felt when, a year or two later, I flung myself headlong into the boundless universe of music.

It was at that exact moment, in November of 1968, that my father’s mother died and left him a monstrously heavy cabinet-model radio-phonograph of unknown but self-evidently ancient vintage. He moved it into my bedroom and dubbed it, logically enough, “the Monster,” and for the next five years, until I took out a small bank loan to buy a decent component system of my own, I used it to listen to music that my genteel grandmother would have found horrific beyond belief.

It was at that exact moment, in November of 1968, that my father’s mother died and left him a monstrously heavy cabinet-model radio-phonograph of unknown but self-evidently ancient vintage. He moved it into my bedroom and dubbed it, logically enough, “the Monster,” and for the next five years, until I took out a small bank loan to buy a decent component system of my own, I used it to listen to music that my genteel grandmother would have found horrific beyond belief.

When I went off to college in 1974, my parents pushed the Monster into the bedroom closet and forgot about it. Not until this summer did my brother, who has a fitting respect for family relics, polish the wooden cabinet to a fare-thee-well, track down a whiskery craftsman old enough to know how to repair its now-obsolete tube amplifier, and restore it to a place of pride at 713 Hickory Drive, the family home in which he and my sister-in-law now reside.

I rejoice to know that the Monster lives again, and I hope someday to play “This Wheel’s on Fire” on its lone speaker—really, really loud.

* * *

Bob Dylan sings “Maggie’s Farm” at the 1965 Newport Folk Festival:

The Who perform “I Can See for Miles” and “My Generation” on The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour in 1967:

I expect a lot out of the books I read, and when they fail to deliver the goods, I toss them aside with a clear conscience and no second thoughts. Life is so very short—and so often shorter than we expect—that it seems a fearful mistake to waste even the tiniest part of it submitting voluntarily to unnecessary boredom. Bad enough that my job sometimes requires me to sit through plays whose sheer awfulness is self-evident well before the end of the first scene….

Read the whole thing here.

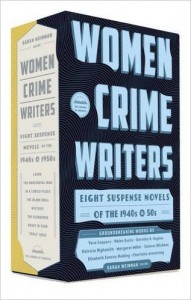

I reviewed Women Crime Writers: Eight Suspense Novels of the 1940s and 1950s, edited by Sarah Weinman, in Saturday’s Wall Street Journal. Here’s an excerpt.

I reviewed Women Crime Writers: Eight Suspense Novels of the 1940s and 1950s, edited by Sarah Weinman, in Saturday’s Wall Street Journal. Here’s an excerpt.

* * *

The Library of America, which specialized once upon a time in reprinting what its dust jackets continue to describe as “America’s best and most significant writing,” has long since succumbed to mission creep. These days it’s as likely to publish Kurt Vonnegut as Edith Wharton, and a fast-growing chunk of its catalog consists of mystery novels and other crime fiction by writers both familiar (Dashiell Hammett) and obscure ( David Goodis). Now comes “Women Crime Writers,” a two-volume anthology edited by Sarah Weinman, a respected critic of the sanguinary genre, that contains eight novels by seven obscure authors and a ringer, Patricia Highsmith, who is still widely remembered for having written “Strangers on a Train” and created Tom Ripley, the sociopath you love to hate,

So are these novels good, significant, neither, or both?

The fact that they were written by women is of no great consequence in and of itself. Women have been writing successful crime novels since the 19th century. Indeed, most of the books in “Women Crime Writers” were popular when they first came out, and Vera Caspary’s “Laura” (1943), Dorothy B. Hughes’s “In a Lonely Place” (1947), Elisabeth Sanxay Holding’s “The Blank Wall” (1947, filmed as “The Reckless Moment”), and Charlotte Armstrong’s “Mischief” (1950, filmed as “Don’t Bother to Knock”) were later turned into movies that starred such A-list actors as Humphrey Bogart, James Mason, Marilyn Monroe and Gene Tierney. Yet none of them, not even Highsmith’s “The Blunderer” (1954), managed to make posterity’s cut. What, then, makes them worthy of revival now?

The answer is that they are all exceptionally fine, as much so as any of the crime novels written by men that were published in this country in the 1940s and 1950s. In particular, I wouldn’t hesitate to stack “The Blunderer,” “In a Lonely Place” and Margaret Millar’s “Beast in View” (1955) up against the best work of Raymond Chandler and Ross Macdonald (who was Millar’s husband), both of whom have already been declared significant by the Library of America.

But the other books in “Women Crime Writers,” very much including Helen Eustis’s “The Horizontal Man” (1946) and Dolores Hitchens’s “Fool’s Gold” (1958), are closely comparable in quality to their companions: Each of them is smartly plotted, tautly written, sharply characterized and not at all dated….

* * *

Read the whole thing here.

The opening sequence of The Reckless Moment, Max Ophüls’ 1949 film version of Elisabeth Sanxay Holding’s The Blank Wall, starring Joan Bennett and James Mason:

| M | T | W | T | F | S | S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | ||||

| 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

| 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 |

| 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 |

| 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 | |

An ArtsJournal Blog