“Kay came to realize that she preferred her books to other people’s company. Reading was not a fallback position for her but an ideal state of being.”

“Kay came to realize that she preferred her books to other people’s company. Reading was not a fallback position for her but an ideal state of being.”

Laura Lippman, What the Dead Know

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City

Annie Ross sings “Twisted,” accompanied by Count Basie on piano, Freddie Green on guitar, Ed Jones on bass, and Sonny Payne on drums. The song is a transcription of a jazz instrumental by Wardell Gray, with lyrics by Ross. This performance was originally telecast on a 1959 episode of Playboy’s Penthouse, hosted by Hugh Hefner:

Annie Ross sings “Twisted,” accompanied by Count Basie on piano, Freddie Green on guitar, Ed Jones on bass, and Sonny Payne on drums. The song is a transcription of a jazz instrumental by Wardell Gray, with lyrics by Ross. This performance was originally telecast on a 1959 episode of Playboy’s Penthouse, hosted by Hugh Hefner:

(This is the latest in a series of arts-related videos that appear in this space each Monday, Wednesday, and Friday.)

By the time most of you read these words, I’ll be somewhere between New York and Lubbock, Texas, where I’m lecturing on “The Future of Theater” at Texas Tech University and paying a visit to the Buddy Holly Center, which is located on—get this—Crickets Avenue.

By the time most of you read these words, I’ll be somewhere between New York and Lubbock, Texas, where I’m lecturing on “The Future of Theater” at Texas Tech University and paying a visit to the Buddy Holly Center, which is located on—get this—Crickets Avenue.

Getting to Lubbock from New York requires that you go somewhere else first, so I’ll be spending two and a half hours en route cooling my heels in the Dallas airport. I’m bringing with me a copy of George, the first volume of Emlyn Williams’ biography, which I trust will keep me happily occupied.

I’m speaking under the auspices of Texas Tech’s Institute for the Study of Western Civilization, and should you happen to be in or near Lubbock, the public is invited to attend. The show starts at 5:30 on Wednesday and admission is free.

For more information, go here.

* * *

Buddy Holly and the Crickets perform “That’ll Be the Day” on The Ed Sullivan Show on December 1, 1957:

I’ve become Mr. Bernstein in Citizen Kane, a middle-aged man with a head full of fireflies, perfectly remembered pinpoints of laughter and sorrow, ecstasy and humiliation, that crowd my consciousness without warning. Would that I also had a few flashes of life-changing insight tucked into my album of mental snapshots, but I guess that’s not how memory works….

Read the whole thing here.

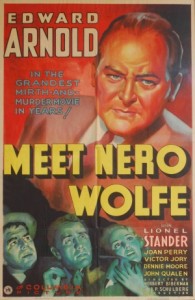

On December 5 I’ll be giving the keynote address at the annual Black Orchid Banquet of the Wolfe Pack, the New York-based society whose members are jointly and severally devoted to the mystery novels of Rex Stout, the creator of Nero Wolfe. Longtime readers of this blog may recall that I read my first Nero Wolfe mystery in 1969, when I was thirteen years old, and have been a fan of Stout’s work ever since. Hence I regard the invitation as a signal honor, especially since my predecessors include Isaac Asimov, Jacques Barzun, Elaine May, Stephen Schwartz, and Donald Westlake.

Paul Hindemith once called America “the land of limited impossibilities.” My own life has been a string of increasingly extreme improbabilities, and every once in a while something happens that cause me to stop dead in my tracks and reflect on just how improbable certain of them have been. I’m not talking about six-alarm spectaculars like the opening nights of The Letter and Satchmo at the Waldorf, but smaller flashes of sudden awareness that cause me to see myself in the moment and ask, What on earth am I doing here? I’ve been trying without much success to imagine how I would have felt if some obliging spirit had taken the trouble to inform my thirteen-year-old self that I’d be speaking to the Wolfe Pack forty-six years later—or that I’d be simultaneously celebrating the thirtieth anniversary of my move to New York City.

Paul Hindemith once called America “the land of limited impossibilities.” My own life has been a string of increasingly extreme improbabilities, and every once in a while something happens that cause me to stop dead in my tracks and reflect on just how improbable certain of them have been. I’m not talking about six-alarm spectaculars like the opening nights of The Letter and Satchmo at the Waldorf, but smaller flashes of sudden awareness that cause me to see myself in the moment and ask, What on earth am I doing here? I’ve been trying without much success to imagine how I would have felt if some obliging spirit had taken the trouble to inform my thirteen-year-old self that I’d be speaking to the Wolfe Pack forty-six years later—or that I’d be simultaneously celebrating the thirtieth anniversary of my move to New York City.

Not long after I became a New Yorker, I was invited to a Park Avenue dinner party at which I was seated next to John Simon. Today John is a semi-retired nonagenarian who scarcely ever inspires public fistfights, but back then he was America’s most controversial drama critic, a fixed star on the cultural horizon who was sufficiently well known to the public at large to have played himself on a 1975 episode of The Odd Couple. I’d been reading his work with close attention for years, and I found the prospect of making conversation with him to be…well, a bit intimidating. Truth to tell, I still do. (If memory serves, my opening gambit was to ask him why his first book had been set in sans serif type, a query that he evidently found unexpected enough not to spend the rest of the evening talking to the person on his right.)

Beyond that, though, I was flummoxed by the mere fact of my presence at the dinner table. What was I doing chatting with the critic whose public feuds with such heavyweight types as Norman Mailer were deemed worthy of coverage in the pages of Entertainment Weekly? It seemed as though I were having an out-of-body experience and was gazing down at myself, or somebody who looked like me, from somewhere in the vicinity of the chandelier.

An old friend recently wrote to ask how I was dealing with the prospect of turning sixty next February. It so happens that he was also present at the very same dinner party at which I met John Simon. What’s more, my friend (who was not yet a friend—we’d only just met) had taken me out to lunch a few weeks earlier. He described that meal in print long after the fact: “Terry was a little reserved, a little anxious, bursting with attention, eager to show how much he knew.” That sounds about right, though my friend couldn’t have known what I was really feeling, which was that my presence at lunch that day was due solely to some gross breakdown in the arrangement of the celestial order.

I felt much the same way when, twenty-one years later, I went to the White House to watch Cyd Charisse receive the National Medal of Arts, having sat by her at dinner the night before and asked her what it was like to dance with Fred Astaire. I knew I was there, but I still couldn’t believe it, any more than I ever found it possible to believe that I knew Bob Brookmeyer well enough to call him a friend.

I felt much the same way when, twenty-one years later, I went to the White House to watch Cyd Charisse receive the National Medal of Arts, having sat by her at dinner the night before and asked her what it was like to dance with Fred Astaire. I knew I was there, but I still couldn’t believe it, any more than I ever found it possible to believe that I knew Bob Brookmeyer well enough to call him a friend.

My guess, for what it’s worth, is that people who grow up in small towns, as I did half a century ago, never quite manage to get used to such not-so-minor miracles, much less learn to take them for granted. I doubt I ever will, and I hope I never do.

* * *

Bob Brookmeyer and John Scofield play “Moonlight in Vermont” on Dutch TV circa 1980:

Since last Tuesday I’ve seen three shows, one in Boston and two on Broadway, and written the following:

Since last Tuesday I’ve seen three shows, one in Boston and two on Broadway, and written the following:

• Two 800-word Wall Street Journal piece that will run on Friday, one of them a review of the shows I saw and the other a “Sightings” column whose subject is the 1955 and 1956 telecasts of Jerome Robbins’ musical version of Peter Pan.

• A 2,500-word review-essay for Commentary on Frank Sinatra.

• A 1,600-word review-essay for National Review on Gore Vidal.

• A 4,000-word lecture called “The Future of Theater” that I’ll be delivering on Wednesday in Lubbock, Texas.

I’m used to working hard, but even for me this was pretty extreme. Fortunately, I don’t have any more copy due until next week, and I have no plans to write between now and then (in part because I have to fly to Texas to give a speech on Wednesday).

On Sunday I rested. I didn’t write a word. Instead I read a book, looked at the art on our walls, listened to Darius Milhaud and William Schuman, watched I Want to Live! and The Third Man, took a walk in the neighborhood, and sent out for sushi.

If you want anything from me this week…you can’t have it.

An ArtsJournal Blog