I’ll be flying to Chicago in two weeks to start rehearsing the Court Theatre’s upcoming production of Satchmo at the Waldorf, which opens in January. We’ve got a lot to do between now and then, but one very big thing is out of the way: John Culbert has completed his set design for the show.

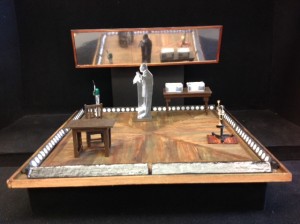

Charles Newell, the director, is opting, as is his wont, for a more conceptual approach to Satchmo. According, John’s set (whose model is pictured at right) is considerably more abstract than the one that Lee Savage designed for Gordon Edelstein’s production, in which he sought to reproduce as closely as possible the physical appearance of Louis Armstrong’s 1971 Waldorf-Astoria dressing room.

Charles Newell, the director, is opting, as is his wont, for a more conceptual approach to Satchmo. According, John’s set (whose model is pictured at right) is considerably more abstract than the one that Lee Savage designed for Gordon Edelstein’s production, in which he sought to reproduce as closely as possible the physical appearance of Louis Armstrong’s 1971 Waldorf-Astoria dressing room.

I still remember with undiminished clarity the morning in December of 2008 when Paul Moravec and I got our first look at Hildegard Bechtler’s set designs for the Santa Fe Opera premiere of The Letter:

It looked like a giant-sized doll’s house, right down to the tiny figures that represented the various characters. We gaped at the model, temporarily stunned into silence. I know how it feels to see the design for the dust jacket of a book that I’ve written, but that’s different: the cover is not the book. An opera, on the other hand, truly exists only in performance, and must be created anew each time it is produced: the score is not the show. As I saw how Hildegard had transformed my libretto into a three-dimensional object, a Biblical phrase popped into my mind: Thus the word was made as flesh.

I’ve undergone the same kind of experience several more times since then, but it hasn’t grown any less exciting. When I opened Charlie’s e-mail this morning and looked at the photographs, I felt like jumping up and down. Yes, John’s set is totally different from Lee’s naturalistic vision of what Satchmo would look like on stage in New England and off Broadway. But it’s neither better nor worse: it is, quite simply, a different way of seeing Satchmo, one that thrills me every bit as much as the old way.

I’ve undergone the same kind of experience several more times since then, but it hasn’t grown any less exciting. When I opened Charlie’s e-mail this morning and looked at the photographs, I felt like jumping up and down. Yes, John’s set is totally different from Lee’s naturalistic vision of what Satchmo would look like on stage in New England and off Broadway. But it’s neither better nor worse: it is, quite simply, a different way of seeing Satchmo, one that thrills me every bit as much as the old way.

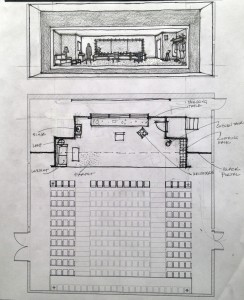

It won’t be the last way, either: Michael Amico, who is designing the set for the Palm Beach Dramaworks production of Satchmo that I’ll be directing in May, is approaching the task from yet another angle, one that reflects my own thinking about how the play should look. Still, that doesn’t mean it’ll be right. Even though I wrote the script, I don’t think of my production as somehow being “righter” than its predecessors. It, too, will be nothing more—or less—than a different way of seeing Satchmo at the Waldorf, and I’ll be just as excited when I see Michael’s sketches for the first time.

That’s part of what makes theater so uniquely special an art form: no matter how familiar the script may be, a play is different every time you do it. If you’re the kind of writer who squirms at such a thought, you’d better stick to novels. Me, I thrive on the electrifying uncertainty of collaboration, and I bless Lee, John, and Michael (not to mention William Elliott, who designed Satchmo’s original 2011 production in Orlando) for giving me the priceless gift of surprise.

“A View from the Bridge” was last seen on Broadway five years ago in a tautly understated production directed by Gregory Mosher that came as close to perfection as a revival can get. Mr. van Hove, by contrast, has opted for the same ostentatious minimalism that he inflicted on “The Little Foxes,” setting Miller’s 1956 drama of incestuous love on the Brooklyn waterfront beneath a giant charcoal-gray cube that hovers over a playing area denuded of props and set pieces. The actors walk around barefoot for no apparent reason, accompanied by snippets of the Fauré Requiem that are played on an endless loop, with a drum tapping at maddeningly metronomic intervals to signify…what? Only, it seems, that Mr. van Hove is so determined to put his personal stamp on “A View from the Bridge” that he doesn’t seem to care whether any of his over-familiar avant-garde tricks are organically related to the script. Instead, they’re poured over it like a rancid sauce.

“A View from the Bridge” was last seen on Broadway five years ago in a tautly understated production directed by Gregory Mosher that came as close to perfection as a revival can get. Mr. van Hove, by contrast, has opted for the same ostentatious minimalism that he inflicted on “The Little Foxes,” setting Miller’s 1956 drama of incestuous love on the Brooklyn waterfront beneath a giant charcoal-gray cube that hovers over a playing area denuded of props and set pieces. The actors walk around barefoot for no apparent reason, accompanied by snippets of the Fauré Requiem that are played on an endless loop, with a drum tapping at maddeningly metronomic intervals to signify…what? Only, it seems, that Mr. van Hove is so determined to put his personal stamp on “A View from the Bridge” that he doesn’t seem to care whether any of his over-familiar avant-garde tricks are organically related to the script. Instead, they’re poured over it like a rancid sauce. The forced internment between 1942 and 1946 of well over 100,000 Japanese-Americans, most of them patriotic U.S. citizens, is now generally seen as a dark blot on this country’s history. It’s also the stuff of sky-high drama, yet next to nothing in the way of noteworthy art has been made out of it. For that reason alone, “Allegiance,” the fictionalized story of a California family that is relocated to a Wyoming camp in 1942, is of obvious interest. It is, however, of no artistic value whatsoever, save as an object lesson in how to write a really bad Broadway musical.

The forced internment between 1942 and 1946 of well over 100,000 Japanese-Americans, most of them patriotic U.S. citizens, is now generally seen as a dark blot on this country’s history. It’s also the stuff of sky-high drama, yet next to nothing in the way of noteworthy art has been made out of it. For that reason alone, “Allegiance,” the fictionalized story of a California family that is relocated to a Wyoming camp in 1942, is of obvious interest. It is, however, of no artistic value whatsoever, save as an object lesson in how to write a really bad Broadway musical.