I had occasion the other day to Google Mel Powell, a child prodigy who became Benny Goodman’s pianist (and a fabulous one, too) at the age of seventeen. Seven years later he switched hats, went to Yale to study composition with Paul Hindemith, started writing classical music, and eventually gave up jazz.

I had occasion the other day to Google Mel Powell, a child prodigy who became Benny Goodman’s pianist (and a fabulous one, too) at the age of seventeen. Seven years later he switched hats, went to Yale to study composition with Paul Hindemith, started writing classical music, and eventually gave up jazz.

I mention all this because one of the things I learned when I Googled Powell was that I’d written a piece about him in 1998 for the Sunday New York Times—a piece I have no memory of writing, even though it sounds just like me:

Trivia question: who was the first jazz musician to win the Pulitzer Prize for music? Hint: it wasn’t Wynton Marsalis. The honor belongs to Mel Powell, who won in 1990 for a two-piano concerto called Duplicates. To be sure, the composer of Duplicates had long since stopped playing jazz by the time he collected his prize. But Powell, who worked with Benny Goodman and Glenn Miller in the 1940s, was for a brief time among the best-known big-band sidemen in America, and when he died on April 24, jazz connoisseurs mourned him not as a relatively obscure composer of nontonal classical music, but as one of the most underrated pianists of the swing era.

When I was younger, I would have boggled at the thought that I might someday forget having written such a piece. Now I know better. In the last twelve years alone, I’ve written close to a thousand columns for The Wall Street Journal and more than eleven thousand postings in this space, not to mention my monthly essays for Commentary and fugitive writings for sundry other magazines and newspapers. What’s surprising isn’t that I forgot having written about Mel Powell, but that I can still remember—usually—what I wrote about last week.

Compared to the true writing machines of the past, of course, I’m a piker. Rex Stout, about whom I’m giving a lecture on Saturday, published thirty-three full-length novels and some forty-odd novellas about Nero Wolfe and Archie Goodwin between 1934 and his death in 1974. H.L. Mencken claimed in the preface to A Mencken Chrestomathy that “the total of my published writings…must run well beyond 5,000,000 words,” an estimate that doubtless fell far short of the actual mark.

Compared to the true writing machines of the past, of course, I’m a piker. Rex Stout, about whom I’m giving a lecture on Saturday, published thirty-three full-length novels and some forty-odd novellas about Nero Wolfe and Archie Goodwin between 1934 and his death in 1974. H.L. Mencken claimed in the preface to A Mencken Chrestomathy that “the total of my published writings…must run well beyond 5,000,000 words,” an estimate that doubtless fell far short of the actual mark.

I can’t claim to come anywhere near such stupendous totals. Still, any reasonably hard-working newspaperman can expect to hit the million-word mark sooner or later if he lives long enough, and I’m sure I passed mine long ago. I started writing for money, after all, in 1977, when I was twenty-one years old. My very first piece was a Kansas City Star review of a classical violinist whose name I no longer remember, though I do recall that he played Richard Strauss’ Violin Sonata, a piece I didn’t like in 1977 and don’t like any better now. I reviewed several hundred classical and jazz performances between then and 1983, carefully clipping copies of each review and mounting them in a pair of fat scrapbooks. By the end of that time I’d also started to write for magazines, and for many years I saved those pieces as well. At one point I went so far as to compile a typewritten bibliography of my magazine articles, an admission that I now blush to make.

I threw out my Kansas City Star scrapbooks and the pile of magazines containing my pieces when, in 2004, I published A Terry Teachout Reader, which contained most of the magazine and newspaper articles written prior to that time that I thought worth preserving. By then it had become apparent that the remainder of my oeuvre would someday be available via searchable online archives, and that there was thus no reason for me to hang onto paper copies of any of it.

More to the point, I was old enough in 2004 to have finally figured out that journalism, mine included, is written to be forgotten. Any journalist who thinks otherwise is kidding himself. Even Mencken, who had a robust ego and did manage to write a few things that seem destined to last, cheerfully admitted in A Mencken Chrestomathy that most of the mountain of words he had piled up between 1899 and 1948 amounted to nothing more than “journalism pure and simple—dead almost before the ink which printed it was dry.”

My own mountain will be no more enduring. As I once wrote in this space, I’d venture to guess that I’ll be better “remembered” over the long haul for having owned one or two pieces of art than for having written anything in the Teachout Reader, and I can’t imagine that my other books will live any longer. How fitting, then, that I should be spending the present and (I assume) final part of my life working in and chronicling the theater, that most radically evanescent of art forms, which exists, like journalism, in the moment and leaves no trace save for fragments of memory and a very short stack of time-defying scripts.

A friend recently sent me a copy of Letters from an Actor, a book written in 1966 by William Redfield, a little-known but once-respected stage actor who is now remembered, if at all, for appearing in the 1975 film version of One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest. In addition, Redfield played Guildenstern in John Gielgud’s modern-dress 1964 Broadway production of Hamlet, in which Richard Burton essayed the title role, and in Letters from an Actor he set down his pungent recollections of what it was like to rehearse that hugely successful but artistically ill-fated staging. He also wrote beautifully—and memorably—about his decision to devote his life to a profession in which virtually all of his achievements were writ on water:

A friend recently sent me a copy of Letters from an Actor, a book written in 1966 by William Redfield, a little-known but once-respected stage actor who is now remembered, if at all, for appearing in the 1975 film version of One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest. In addition, Redfield played Guildenstern in John Gielgud’s modern-dress 1964 Broadway production of Hamlet, in which Richard Burton essayed the title role, and in Letters from an Actor he set down his pungent recollections of what it was like to rehearse that hugely successful but artistically ill-fated staging. He also wrote beautifully—and memorably—about his decision to devote his life to a profession in which virtually all of his achievements were writ on water:

Acting is the most mortal of the arts. Like perishable foods, it must be taken fresh or not at all….Line drawings, quick sketches. An intuitive understanding of what reaches people today—loving, hating, and struggle. The actor must be deep in his heart and quick with his hands, catch Pegasus by the heel by riding a tiger, have the soul of a fairy and the hide of a walrus, change himself from night to night and alter his psyche from year to year. He is a chameleon gone aesthetic; a shade with a purpose. A second-story man who breaks into your house not to take but to give. Actors who do not keep pace with today will go under. Like lemmings, they will drown even in the neap tide. For the actor, today is the future.

So, too, for the journalist—and yet there are far worse fates than to be forced to live in an unending succession of moments. As insignificant as I am in the grand scheme of things, I still think—I hope—that I help in my little way to make the world of art a better place. And if not? Then my failed attempts will crumble into dust soon enough.

As for Mel Powell, he left us in 1998. His death, in fact, was the occasion for the New York Times tribute that I forgot having written. But the improvised-on-the-spot solos that he recorded in the Forties and Fifties are still with us, and still marvelous to hear. Famous he isn’t, but neither is he altogether forgotten. I should be so lucky.

* * *

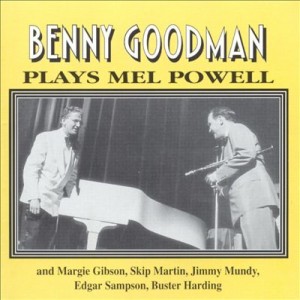

Benny Goodman, Lionel Hampton, and Mel Powell play “Stealin’ Apples” in the 1948 film A Song Is Born, directed by Howard Hawks and starring Danny Kaye:

Benny Goodman and Mel Powell play together on The Merv Griffin Show in 1976:

An excerpt from a film of a live stage performance of John Gielgud’s 1964 production of Hamlet, with Richard Burton in the title role, Hume Cronyn as Polonius, Clement Fowler as Rosencrantz, and William Redfield as Guildenstern:

One reason why it works so well is that Ms. Stone has followed to the letter Stephen Sondheim’s shrewd advice not to stage the musical as “mere camp.” Accordingly, her “women” are men dressed in Milton Berle-style drag. They act like women—sort of—but don’t look like them in the least. Philia (David Turner), the Roman courtesan with whom Hero (Bobby Conte Thornton) falls hopelessly in love, isn’t even pretty and wears a wig that could have come from a dime store. cMs. Stone’s purpose is to present the well-worn dumb-blonde stereotypes utilized by Mr. Sondheim, Larry Gelbart and Burt Shevelove, the authors of “Funny Thing” (as well as Plautus, the third-century Roman playwright on whose farces it is freely based), in a new light. “It feels like an all-male show already because these female roles are male constructs,” she explained in a recent interview. If, then, they are played by male actors whose maleness is immediately obvious to the audience, the absurdity of the stereotypes will become just as obvious.

One reason why it works so well is that Ms. Stone has followed to the letter Stephen Sondheim’s shrewd advice not to stage the musical as “mere camp.” Accordingly, her “women” are men dressed in Milton Berle-style drag. They act like women—sort of—but don’t look like them in the least. Philia (David Turner), the Roman courtesan with whom Hero (Bobby Conte Thornton) falls hopelessly in love, isn’t even pretty and wears a wig that could have come from a dime store. cMs. Stone’s purpose is to present the well-worn dumb-blonde stereotypes utilized by Mr. Sondheim, Larry Gelbart and Burt Shevelove, the authors of “Funny Thing” (as well as Plautus, the third-century Roman playwright on whose farces it is freely based), in a new light. “It feels like an all-male show already because these female roles are male constructs,” she explained in a recent interview. If, then, they are played by male actors whose maleness is immediately obvious to the audience, the absurdity of the stereotypes will become just as obvious. •

•