“I’ll bet Shakespeare compromised himself a lot; anybody who’s in the entertainment industry does to some extent.”

“I’ll bet Shakespeare compromised himself a lot; anybody who’s in the entertainment industry does to some extent.”

Christopher Isherwood (interviewed in the Paris Review, Spring 1974)

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City

A week after bringing home my new MacBook Air, I’m more or less used to it. To be sure, I have yet to explore any of its more recherché capabilities, but now that I’ve written two Wall Street Journal columns and sent and received hundreds of e-mails, I feel confident of my ability to carry on my usual computer-related activities in a recognizably normal way, which is what really matters to a journalist who spends most of any given day plugged into the great world of cyberspace.

A week after bringing home my new MacBook Air, I’m more or less used to it. To be sure, I have yet to explore any of its more recherché capabilities, but now that I’ve written two Wall Street Journal columns and sent and received hundreds of e-mails, I feel confident of my ability to carry on my usual computer-related activities in a recognizably normal way, which is what really matters to a journalist who spends most of any given day plugged into the great world of cyberspace.

Therein lay the source of the anxieties that kept me from switching computers sooner: I didn’t know that I wouldn’t have to learn anything dramatically new in order to use my MacBook Air. Yes, it’s much faster and has a far more powerful battery than its predecessor, but there’s an essential continuity between Old Laptop and New Laptop. To put it another way, my life isn’t significantly different from the way it was last week—it’s just easier.

This distinction isn’t as widely understood as it should be. Most new technologies make our lives easier without changing them other than superficially. The compact disc, for example, was a convenience, not a revolution. Unlike the iPod, it didn’t alter our relationship to the world of music. The answering machine, by contrast, really did transform the way in which we used the telephone by making it possible to screen incoming calls. As soon as that possibility became a reality, the place of the telephone in daily life underwent a profound change, and never changed back.

This distinction isn’t as widely understood as it should be. Most new technologies make our lives easier without changing them other than superficially. The compact disc, for example, was a convenience, not a revolution. Unlike the iPod, it didn’t alter our relationship to the world of music. The answering machine, by contrast, really did transform the way in which we used the telephone by making it possible to screen incoming calls. As soon as that possibility became a reality, the place of the telephone in daily life underwent a profound change, and never changed back.

Not everyone is open to such change. Sooner or later each generation comes to a great technological divide, a chasm that most of its aging members are unable or unwilling to cross. For my mother, who was born mere weeks before the Great Depression, that chasm was the invention of the personal computer. She owned an answering machine—I bought it for her—but she never screened her calls, nor did she learn how to use a computer. When the PC became a routine part of American life, she was officially old. The world had passed her by.

I was born in 1956, twenty-seven years after my mother, which means that I lived through the early years of the rise of personal computing. Indeed, my initial exposure to screen-based electronic word processing, as I recalled in this space eleven years ago, came long before I managed to save up enough money to buy my first IBM desktop computer:

I was born in 1956, twenty-seven years after my mother, which means that I lived through the early years of the rise of personal computing. Indeed, my initial exposure to screen-based electronic word processing, as I recalled in this space eleven years ago, came long before I managed to save up enough money to buy my first IBM desktop computer:

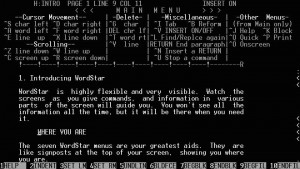

I first used a computer for word processing some time around 1979, when the Kansas City Star told me that I had to start writing my concert reviews directly on its mainframe computing system rather than typing them on an IBM Selectric and having them scanned into the system optically. I was stunned—that really is the word for it—by my first encounter with word processing, and recognized at once that it would change every writer’s life for the better. I first used a personal computer in 1985, when I started writing my pieces on the PC of Harper’s Magazine after hours (and not infrequently on company time, too!). I bought an identical IBM computer two years later when I went to work for the New York Daily News, and used it for the next decade and a half.

Needless to say, I was right. Personal computers transformed the working habits of every writer who, like me, chose to use them. But they did much more than that: they upended the daily lives of everyone who, unlike my mother, was young enough to leap across the technological chasm and embrace their revolutionary power. No day passes when I am not grateful for having been born in time to join that revolution.

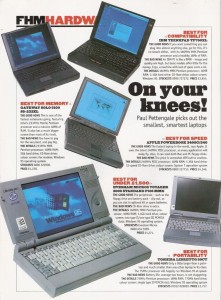

The next major upheaval in my computing life came in 1995, when I bought my first laptop. By then I’d started working in earnest on The Skeptic, my H.L. Mencken biography, and it wasn’t long before I figured out that I was going to need to use a laptop in order to transcribe unpublished passages from Mencken’s papers, most of which he had deposited in Baltimore’s Enoch Pratt Free Library and which I couldn’t examine anywhere else.

The next major upheaval in my computing life came in 1995, when I bought my first laptop. By then I’d started working in earnest on The Skeptic, my H.L. Mencken biography, and it wasn’t long before I figured out that I was going to need to use a laptop in order to transcribe unpublished passages from Mencken’s papers, most of which he had deposited in Baltimore’s Enoch Pratt Free Library and which I couldn’t examine anywhere else.

The machine I bought was a chunky gray slab of plastic that was similar in size and weight to an old-fashioned Sears Christmas catalogue. Elegant it wasn’t, but it made it possible for me to input material from the Mencken Collection on the spot, as well as to write in hotel rooms and on planes and trains. What had once been impossible soon became essential, and in due course my professional life underwent yet another upheaval: I scrapped my desktop computer (and, perhaps not coincidentally, my landline) shortly after the twentieth century gave way to the twenty-first. Compared to that giant step, buying a MacBook Air was more like buying a new car.

So when will I arrive at my own great divide? Since I have yet to acquire a smartphone, some might say that it’s already here, but I know better. I’ve never been an early adopter—I prefer to let others work out the bugs—and so I deliberately chose not to buy an iPhone until after I’d finally gotten a new laptop and familiarized itself with its idiosyncratic workings. Having done so without incident, I expect I’ll make the Next Bold Leap Forward some time in the next month or two. And after that? I don’t doubt that a time will come when I no longer feel equal to the task of keeping up with technological change, but my guess is that dread day of reckoning is still a long way off.

It helps that I’ve never been scared by the prospect of change. In 2005 I blogged about some of the technologies that I’d already outlived—typewriters, fax machines, black discs, snail mail—and marveled at the vertiginous velocity of their onrushing obsolescence. What surprises me in retrospect about that posting is that I already took for granted the fact that I no longer had a landline, so much so that I didn’t even bother to mention it. That’s what it means to live in an age of constant change: you take the damnedest things for granted.

It helps that I’ve never been scared by the prospect of change. In 2005 I blogged about some of the technologies that I’d already outlived—typewriters, fax machines, black discs, snail mail—and marveled at the vertiginous velocity of their onrushing obsolescence. What surprises me in retrospect about that posting is that I already took for granted the fact that I no longer had a landline, so much so that I didn’t even bother to mention it. That’s what it means to live in an age of constant change: you take the damnedest things for granted.

All of which reminds me that I didn’t write a word during the four days that I spent without a computer. Strange as it may sound, that didn’t bother me in the least. In fact, I rather enjoyed it. What really irked me was that I had to call a restaurant to make a dinner reservation instead of using OpenTable. Somehow I find that encouraging.

* * *

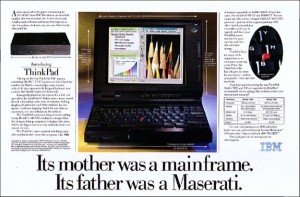

A 1977 TV ad for IBM’s first portable computer:

An IBM ThinkPad commercial from the Nineties:

The Byrds perform Bob Dylan’s “You Ain’t Goin’ Nowhere” on a 1968 episode of Playboy After Dark. Roger McGuinn is the lead singer, accompanied by Clarence White on lead guitar, John York on bass, and Gene Parsons on drums:

(This is the latest in a series of arts-related videos that appear in this space each Monday, Wednesday, and Friday.)

I continue to adjust more or less smoothly to life with my new MacBook Air. Alas, nobody’s perfect, and I hit a pothole yesterday with my e-mail program, which proceeded to swallow a half-dozen or so personal messages that I had yet to answer. Most of them I remember, but one or two have slipped my aging mind.

I continue to adjust more or less smoothly to life with my new MacBook Air. Alas, nobody’s perfect, and I hit a pothole yesterday with my e-mail program, which proceeded to swallow a half-dozen or so personal messages that I had yet to answer. Most of them I remember, but one or two have slipped my aging mind.

If you wrote to me for personal reasons at any time in the last week and a half and have so far failed to receive an answer, would you please be so kind as to send your e-mail again? I promise this time to answer it as punctually as possible.

In today’s Wall Street Journal I review two musicals that couldn’t be more different, the New York premiere of First Daughter Suite and the Broadway premiere of Dames at Sea. Here’s an excerpt.

* * *

Michael John LaChiusa is a singularly gifted, hugely original maker of musical theater who, like Stephen Sondheim before him, insists on going his own idiosyncratic way. While his shows rarely have any obvious commercial appeal, the Public Theater, to its infinite credit, keeps on producing them. Hence “First Daughter Suite,” a quartet of fictional portraits of the daughters and wives of Richard Nixon, Gerald Ford, Jimmy Carter, Ronald Reagan and George Bush the elder. No, it’s not especially political. Instead, Mr. LaChiusa has given us something far more interesting, a four-part dramatic poem about the pathos of unsought fame whose score is as beautiful as anything that Mr. Sondheim ever wrote in his prime.

Michael John LaChiusa is a singularly gifted, hugely original maker of musical theater who, like Stephen Sondheim before him, insists on going his own idiosyncratic way. While his shows rarely have any obvious commercial appeal, the Public Theater, to its infinite credit, keeps on producing them. Hence “First Daughter Suite,” a quartet of fictional portraits of the daughters and wives of Richard Nixon, Gerald Ford, Jimmy Carter, Ronald Reagan and George Bush the elder. No, it’s not especially political. Instead, Mr. LaChiusa has given us something far more interesting, a four-part dramatic poem about the pathos of unsought fame whose score is as beautiful as anything that Mr. Sondheim ever wrote in his prime.

The one-act musicals that make up “First Daughter Suite” vary widely in style. “Happy Pat” is a dark comedy about the White House wedding of Tricia Nixon (Betsy Morgan) in which Pat Nixon (Barbara Walsh) is visited by the censorious ghost of her husband’s Quaker mother (Theresa McCarthy). “Amy Carter’s Fabulous Dream Adventure” is a surreal fantasy in which young Amy (Carly Tamer) takes various Carters and Fords on a fantastic voyage to Iran. “Patti by the Pool” portrays a savage skirmish between Patti Davis (Caissie Levy) and Nancy Reagan (Alison Fraser). In “In the Deep Bosom of the Ocean Buried,” Laura Bush (Rachel Bay Jones) tries to lure Barbara (Mary Testa) onto the campaign trail, not knowing that her mother-in-law is preoccupied by memories of her daughter Robin (Ms. McCarthy), who died of leukemia at the age of four.

What all four acts have in common is that they show us the private lives of a group of women who have paid in variously painful ways for their unseen husbands’ ambitions….

“Dames at Sea,” the ultra-campy 1966 musical about the you’ll-come-back-a-star backstage movie musicals of the early ’30s, has finally made it to Broadway. I’m not sure why, since the point of the show, which employs just six performers (one of whom plays two parts) and whose original downtown run opened the door to fame for Bernadette Peters, is that it’s a low-budget miniature send-up of the genre. Staging it on Broadway would seem to be somewhat beside the point, though this gussied-up revival, directed and choreographed by Randy Skinner, is nothing if not charming. If you like high-velocity tap dancing, you’ll see (and hear) plenty of it…

“Dames at Sea,” the ultra-campy 1966 musical about the you’ll-come-back-a-star backstage movie musicals of the early ’30s, has finally made it to Broadway. I’m not sure why, since the point of the show, which employs just six performers (one of whom plays two parts) and whose original downtown run opened the door to fame for Bernadette Peters, is that it’s a low-budget miniature send-up of the genre. Staging it on Broadway would seem to be somewhat beside the point, though this gussied-up revival, directed and choreographed by Randy Skinner, is nothing if not charming. If you like high-velocity tap dancing, you’ll see (and hear) plenty of it…

So what’s not to like? Nothing whatsoever—but there isn’t enough to love about “Dames at Sea,” which may have seemed sufficiently witty a half-century ago but has long since been outclassed by the encyclopedically knowing musical-comedy spoofery of “The Drowsy Chaperone.” Compared with that big-brain homage, “Dames at Sea” isn’t much more clever than a college show…

* * *

To read my review of First Daughter Suite, go here.

To read my review of Dames at Sea, go here.

In today’s Wall Street Journal “Sightings” column I discuss adaptations of well-known works of art that are better than (or as good as) the originals. Here’s an excerpt.

* * *

If you’re the kind of adventure-loving theatergoer who can’t think of a good reason to see “The Gin Game” again, you might want to check out New Yiddish Rep’s off-Broadway production of “Death of a Salesman,” which runs through Nov. 22 at the Castillo Theatre. Why? Because it’s being done in Yiddish, the amalgam of Hebrew and German that was heard in the ghettoes of Central Europe prior to the Holocaust and continues to be spoken by Hasidic and Orthodox Jews throughout the world.

I have yet to see this staging, but it’s clear from reading the script, which was translated in 1951 by Joseph Buloff, that “Death of a Salesman” has profited immensely from the change in languages. Even though Willy and Linda Loman are as self-evidently Jewish as bagels and lox, Miller deliberately deracinated their characters on the page to make their plight seem more universal to Gentile audiences. That’s why their lines sound more authentic in Yiddish (which you don’t have to speak to follow the production—it uses English-language supertitles). Instead of the inflated pseudo-poetry of Miller’s original text, you get the guttural lilt of a homely tongue that comes naturally to such beleaguered souls. In Yiddish, Linda’s notoriously clumsy “Attention, attention must be finally paid to such a person” has the stark ring of a death sentence: “Achtung gebn af im.”

I have yet to see this staging, but it’s clear from reading the script, which was translated in 1951 by Joseph Buloff, that “Death of a Salesman” has profited immensely from the change in languages. Even though Willy and Linda Loman are as self-evidently Jewish as bagels and lox, Miller deliberately deracinated their characters on the page to make their plight seem more universal to Gentile audiences. That’s why their lines sound more authentic in Yiddish (which you don’t have to speak to follow the production—it uses English-language supertitles). Instead of the inflated pseudo-poetry of Miller’s original text, you get the guttural lilt of a homely tongue that comes naturally to such beleaguered souls. In Yiddish, Linda’s notoriously clumsy “Attention, attention must be finally paid to such a person” has the stark ring of a death sentence: “Achtung gebn af im.”

As I worked my way through the transliterated script of “Toyt fun a Seylsman,” I caught myself thinking of Deaf West Theater’s revival of “Spring Awakening,” which is being performed on Broadway in a mixture of American Sign Language (used by the deaf actors) and spoken and sung English (used by the hearing actors). Even though I don’t like the musical, I was thrilled by the staging. Just as the use of Yiddish in “Death of a Salesman” makes manifest what was only latent in Miller’s English-language version, so does the use of ASL in “Spring Awakening” add a rich new layer of visual symbolism to a musical with an expressively inadequate score. In other words, translating these two shows has made them better.

Such retrospective improvements are not unknown in the world of art. Indeed, David Ives has gone so far as to coin the word “translaptation” to describe his own translations of such obscure 17th- and 18th-century French comedies as Jean-François Regnard’s “The Heir Apparent” and Pierre Corneille’s “The Liar,” in which he recasts the text in crisply contemporary iambic pentameter and jiggers with the plot to spectacular comic effect. But none of these shows, not even “Death of a Salesman,” is a great work of art by any stretch of the imagination, and that leads me to wonder: Might it also be possible to improve on a masterwork?

Perhaps not, but when a major artist revisits a masterwork, strange and wonderful things can happen….

* * *

Read the whole thing here.

A scene from New Yiddish Rep’s 2013 production of Waiting for Godot, translated into Yiddish by Shane Baker and subtitled in English:

The assassination scene from the original 1934 version of Alfred Hitchcock’s The Man Who Knew Too Much, written by Charles Bennett and D.B. Wyndham-Lewis. The piece performed at the Royal Albert Hall concert is Arthur Benjamin’s Storm Clouds Cantata, written specifically for performance in the film. It was reused when Hitchcock remade the film in 1956:

The assassination scene from the original 1934 version of Alfred Hitchcock’s The Man Who Knew Too Much, written by Charles Bennett and D.B. Wyndham-Lewis. The piece performed at the Royal Albert Hall concert is Arthur Benjamin’s Storm Clouds Cantata, written specifically for performance in the film. It was reused when Hitchcock remade the film in 1956:

(This is the latest in a series of arts-related videos that appear in this space each Monday, Wednesday, and Friday.)

An ArtsJournal Blog