Mrs. T and I went to see the Paul Taylor Dance Company in Florida this past February, an experience that I described in this space shortly thereafter:

When it was all over, I talked nonstop about Taylor and Balanchine as I drove Mrs. T back to our hotel. I was boiling over with an excitement that I hadn’t felt since the last time I saw a great dance that was new to me. We’ve got to do this again right away, I told myself, knowing full well that the Paul Taylor Dance Company will be performing at Lincoln Center next month.

Needless to say, I’d like nothing better than to take Mrs. T to see Esplanade and Company B and Piazzolla Caldera and The Rite of Spring…but will I? My calendar, after all, is already jammed with plays that urgently require my professional attention, and it will be, as it always is, fearfully hard for me to summon up sufficient energy to spend any of my rare nights off doing something that I don’t absolutely have to do, no matter how much I want to do it.

Is that a reason? Or an excuse?

Both, I guess, since we didn’t go back in March, nor did we subsequently seek out dance of any kind (not counting Broadway, which is forever with us). But the seed was planted, and after I read Jacques d’Amboise’s I Was a Dancer in Chicago last month, I knew that I had to take Mrs. T to see New York City Ballet at the earliest possible opportunity. So when I saw the other day that the company was performing George Balanchine’s Liebeslieder Walzer and that there were two performances remaining before The Nutcracker took over the Koch Theater for the winter, I made haste to order a pair of tickets for the Sunday matinee.

Both, I guess, since we didn’t go back in March, nor did we subsequently seek out dance of any kind (not counting Broadway, which is forever with us). But the seed was planted, and after I read Jacques d’Amboise’s I Was a Dancer in Chicago last month, I knew that I had to take Mrs. T to see New York City Ballet at the earliest possible opportunity. So when I saw the other day that the company was performing George Balanchine’s Liebeslieder Walzer and that there were two performances remaining before The Nutcracker took over the Koch Theater for the winter, I made haste to order a pair of tickets for the Sunday matinee.

I last saw Liebeslieder Walzer in 2004. It was the first time that I’d seen NYCB since I’d finished writing All in the Dances: A Brief Life of George Balanchine, in which the following description of the ballet can be found:

Liebeslieder Walzer is set not in a sky-blue void but a candle-lit ballroom where four aristocratic-looking young couples in evening dress spend an hour waltzing together, accompanied by the four singers and two pianists with whom they share the stage. The couples are entangled in subtly differing ways (one of the women, for example, appears to be older than her partner-lover), though there is no plot or Tudor-style “acting” to give away their intimate secrets. Romantic ends are achieved by modern means: all you see are the setting and the steps, with everything else left to the imagination. The dancers drift outdoors into a moonlit garden and the curtain falls for a breathless moment. When it rises again, the ballroom itself is flooded with moonlight, the women are wearing tutus and toe shoes, and the decorous ballroom dancing of the first act is replaced by the heightened gestures of ballet. At the end, the women reappear in their party gowns, and the couples listen in stillness to the last waltz, whose words, sung in German, are by Goethe:

Now, Muses, enough!

You strive in vain to show

How joy and sorrow alternate in loving hearts.

You cannot heal the wounds inflicted by love;

But assuagement comes from you alone….The costume change midway through Liebeslieder Walzer is a stroke of fantasy as stunning in its quieter way as the climactic flying lifts of The Four Temperaments. Balanchine revealed its meaning to Bernard Taper: “In the first act, it’s the real people that are dancing. In the second act, it’s their souls.” But more than a few members of the ballet’s earliest audiences, bored by its unending succession of “love-song waltzes,” would slip out of the theater during the pause between acts. In an oft-told anecdote that may or may not be true, Balanchine and Lincoln Kirstein were watching a performance together. “Look how many people are leaving, George,” Kirstein moaned, to which Balanchine replied, “Ah, but look how many are staying!” Today, though New York City Ballet now performs Liebeslieder Walzer only infrequently, it is loved by connoisseurs for what Arlene Croce has called its “persistent note of melancholy and tragic remorse,” and there are those, myself included, who regard it as their favorite Balanchine ballet of all.

The performance that I saw fifteen years ago featured Kyra Nichols, the Balanchine dancer who meant the most to me in my balletgoing days. I wrote about it in my Washington Post column, calling it “a night to die for—and cry for.” Yet I didn’t go back when NYCB revived Liebeslieder Walzer in 2009. By then Nichols had retired, and my duties as a drama critic had made my own life so crowded that dance was forced to give way to more pressing matters.

The performance that I saw fifteen years ago featured Kyra Nichols, the Balanchine dancer who meant the most to me in my balletgoing days. I wrote about it in my Washington Post column, calling it “a night to die for—and cry for.” Yet I didn’t go back when NYCB revived Liebeslieder Walzer in 2009. By then Nichols had retired, and my duties as a drama critic had made my own life so crowded that dance was forced to give way to more pressing matters.

Not altogether: Mrs. T and I went to see Miami City Ballet on our first trip to Florida that winter. The company performed Ballet Imperial, Balanchine’s 1941 dance version of Tchaikovsky’s Second Piano Concerto, and its splendor and virtuosity overwhelmed her.

As for me, I went back to see NYCB in 2011 for professional reasons, but the experience, as I wrote here, turned out to be unexpectedly melancholy:

The sad truth is that I felt rather like a ghost at the party, looking at Maria Kowroski in Vienna Waltzes and remembering Suzanne Farrell’s farewell performance in the same ballet twelve years ago….I knew long before the evening was over that I no longer felt altogether at home in the world of ballet, and it wasn’t until I left the theater that I regained my equilibrium and was myself again.

Two years went by before my next visit, when I took Mrs. T to see three more Balanchine ballets. Alas, The Four Temperaments, for me the greatest of all dances by Balanchine or anyone else, wasn’t on the program, but what there was, as Spencer Tracy says of Katharine Hepburn in Pat and Mike, was choice: Serenade, Stravinsky Violin Concerto and Stars and Stripes. “You can take me to the ballet any time,” Mrs. T assured me as we left the theater. And so—finally—I did.

We ran into Elizabeth Kendall outside the Koch Theater. No sooner did Elizabeth and I exchange omigod-how-long-has-it-been greetings than she told me that she was using All in the Dances as an introductory text in one of her classes, which made me blush with pleasure. For a brief moment I felt a little less out of touch with the tight little world of dance of which I had once been part.

Then I walked past a poster announcing that we were about to see “Jennie Somogyi’s Farewell Performance.” Somogyi, who joined NYCB in 1994, is a member of the last generation of up-and-coming dancers whose careers I once followed attentively. Now, at thirty-eight, she was retiring, and it was news to me: I’d shown up at her last performance by accident. Once more I felt hopelessly out of it, and old to boot.

Then I walked past a poster announcing that we were about to see “Jennie Somogyi’s Farewell Performance.” Somogyi, who joined NYCB in 1994, is a member of the last generation of up-and-coming dancers whose careers I once followed attentively. Now, at thirty-eight, she was retiring, and it was news to me: I’d shown up at her last performance by accident. Once more I felt hopelessly out of it, and old to boot.

Inside the theater, we sat down next to a family of four whose small talk suggested that they weren’t regular dancegoers. Mrs. T introduced us, and the husband, who had a Jersey accent, explained that they were friends and neighbors of Somogyi and her own family (her husband is a New Jersey policeman) and had come to cheer her on.

“So you know about this ballet stuff, huh?” he said to me.

“I used to write about it.”

“Then lemme ask you somethin’. What’s the deal about Jennie? Was she really as good as they say?”

“You bet,” I said. “Class A.”

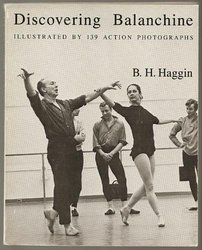

I won’t pretend to judge the merits of the performance of Liebeslieder Walzer that we saw yesterday afternoon. Not only is my critic’s eye out of practice, but it was also dimmed by tears. Instead I’ll cite two experts, one of whom, the late B.H. Haggin, I used to know many years ago. Haggin liked to quote a remark that an unnamed actor and theater director made to him after the two men saw a Balanchine ballet danced at New York’s City Center back in the Fifties: “The truth is that what is significant in the theater today is being produced right here.”

I won’t pretend to judge the merits of the performance of Liebeslieder Walzer that we saw yesterday afternoon. Not only is my critic’s eye out of practice, but it was also dimmed by tears. Instead I’ll cite two experts, one of whom, the late B.H. Haggin, I used to know many years ago. Haggin liked to quote a remark that an unnamed actor and theater director made to him after the two men saw a Balanchine ballet danced at New York’s City Center back in the Fifties: “The truth is that what is significant in the theater today is being produced right here.”

Part of what Haggin was getting at is that whatever else they were, Balanchine’s dances were theater above all. I can’t imagine that observation being more to the point, then or now, than in the case of Liebeslieder Walzer, which to my mind is one of the most extraordinary works of lyric theater created in the twentieth century, a masterpiece that is all the more miraculous because it is a plotless ballet whose poetic effect derives entirely from the fusion of music, movement, and décor. Richard Wagner couldn’t have conceived of a more radically unified work of art.

Part of what Haggin was getting at is that whatever else they were, Balanchine’s dances were theater above all. I can’t imagine that observation being more to the point, then or now, than in the case of Liebeslieder Walzer, which to my mind is one of the most extraordinary works of lyric theater created in the twentieth century, a masterpiece that is all the more miraculous because it is a plotless ballet whose poetic effect derives entirely from the fusion of music, movement, and décor. Richard Wagner couldn’t have conceived of a more radically unified work of art.

The other “expert” is the choreographer himself. “Why are you stingy with yourselves?” Balanchine used to say to his dancers. “Why are you holding back? What are you saving for—for another time? There are no other times. There is only now. Right now.” I wonder whether Jennie Somogyi thought of those oft-quoted words as she waited in the wings. For her, there was nothing left but now, and she danced that way, with total concentration and commitment, from the first downbeat to the final curtain.

When it was all over, Mrs. T and I crossed the street to P.J. Clarke’s to grab a bite to eat. We didn’t say much, not even that we’d do it again right away. Maybe we will and maybe we won’t: life will make that decision for us. Like Mr. B said, there is only now. But I have no doubt that neither one of us will soon forget what we saw yesterday, and that’s good enough for me.

* * *

New York City Ballet dances the first and last sections of George Balanchine’s Liebeslieder Walzer in a 1973 film directed by Klaus Lindemann. The score is Brahms’ Liebeslieder Walzer and Neue Liebeslieder Walzer, Opp. 52 and 65. The dancers are Karin von Aroldingen and Peter Martins, Patricia McBride and Frank Ohman, Kay Mazzo and Conrad Ludlow, and Violette Verdy and Jean-Pierre Bonnefous. (Ludlow and Verdy created their roles in the original 1960 production.) The singers are Erika Benade, Otto P. Kuster, Helmut Lang, and Christa Willenberg and the pianists are Dianne Chilgren and Gordon Boelzner: