I drove into Manhattan three Saturdays ago to see a pair of Broadway matinees. When I got to our apartment and checked my e-mail, I found a message from the Metropolitan Museum reminding me that Sargent: Portraits of Artists and Friends was closing the next day. My passion for the paintings of John Singer Sargent goes back a long way, but having spent most of the summer on the road or in Connecticut, I found it impossible to get into the city to see this important exhibition. So while I hate going to blockbuster shows on weekends—I usually go to the press previews—I figured that I’d be smart to make an exception this time.

I drove into Manhattan three Saturdays ago to see a pair of Broadway matinees. When I got to our apartment and checked my e-mail, I found a message from the Metropolitan Museum reminding me that Sargent: Portraits of Artists and Friends was closing the next day. My passion for the paintings of John Singer Sargent goes back a long way, but having spent most of the summer on the road or in Connecticut, I found it impossible to get into the city to see this important exhibition. So while I hate going to blockbuster shows on weekends—I usually go to the press previews—I figured that I’d be smart to make an exception this time.

I arrived at 10:30, half an hour after the museum opened, by which time the crowds were already big enough to make it hard to spend more than a few harried moments in front of any one painting. After going through the show twice, I retreated to the Met’s nearby Cézanne gallery, which was deserted save for a guard, and spent a few restful minutes contemplating its contents in solitude. Then I wandered idly through the rest of the museum, coming back to the Sargent show an hour later. By then the situation was all but impossible, so I pushed my way to a half-dozen particular pieces that had caught my eye, then fled to the elevator and headed for Broadway, where Fool for Love and my friend Zephyr Teachout awaited me.

Incredibly, more than two years had gone by since my last visit to the Met, during which time the triumph of the smartphone became complete. My heart sank to see how many people pulled out their phones to snap pictures as they approached the paintings, only then looking up to see what they’d purportedly come to see. At least they weren’t using selfie sticks, the Met having banned them from the premises earlier this year. Even so, I can’t help but wonder why such folk bother to go to museums at all, the point of doing so being to look at paintings rather than merely to document the fact that you stood in front of them.

Incredibly, more than two years had gone by since my last visit to the Met, during which time the triumph of the smartphone became complete. My heart sank to see how many people pulled out their phones to snap pictures as they approached the paintings, only then looking up to see what they’d purportedly come to see. At least they weren’t using selfie sticks, the Met having banned them from the premises earlier this year. Even so, I can’t help but wonder why such folk bother to go to museums at all, the point of doing so being to look at paintings rather than merely to document the fact that you stood in front of them.

For my part, I stood in front of as many paintings as possible, then spent the next few days thinking about what I’d seen. A few of them, including Madame X and Dr. Pozzi at Home, were widely familiar to the public at large, but nearly all of the others were new to me, and I’d only seen in reproduction most of the portraits with which I was already familiar.

Most of Sargent’s subjects were also unknown to me, and it struck me as I moved through the show that a portrait of a person about whom you know nothing is in a sense an abstract painting. This may help to explain why so many art critics contend that Sargent’s portraits, for all their virtuosity, are not psychologically penetrating. If, on the other hand, you bring some prior knowledge of the subject to the table, then your relationship to a portrait is bound to be altered, perhaps dramatically so.

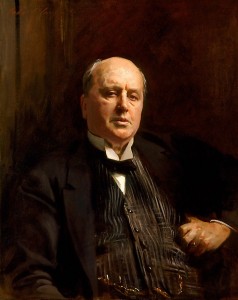

As it happened, I did know a fair amount about the subjects of several of the portraits on display at the Met, and without exception those portraits struck me as extraordinarily revealing, none more so than Sargent’s justly celebrated painting of Henry James.

As it happened, I did know a fair amount about the subjects of several of the portraits on display at the Met, and without exception those portraits struck me as extraordinarily revealing, none more so than Sargent’s justly celebrated painting of Henry James.

The wall label is worth quoting:

In 1913, a group of James’s friends decided to commission a portrait in celebration of his seventieth birthday. Sargent was the obvious choice despite confiding to the novelist that having “stopped portraiture for these past three or four years, he had quite ‘lost his nerve’ about it.” Sargent’s painting is a masterly study of an enigmatic literary genius and a sympathetic depiction of an aging friend. James’s pose, with his thumb hooked into the armhole of his vest, suggests studied informality. His domed head is luminous with intelligence.

The operative phrase here is “studied informality.” None of Sargent’s subjects seem ever to have smiled for him. Their expressions are almost always detached and non-committal, if not altogether formal, and this one is no exception—yet James’ essence, however guarded, still comes through.

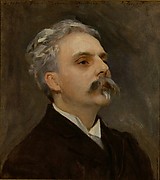

A few steps away hung a similarly revealing painting of the great French composer Gabriel Fauré, one of Sargent’s most intimate friends. It conveys exactly what Aaron Copland, another admirer of Fauré’s music, had in mind when he spoke of his “restraint and classic sense of order…his delicacy, his reserve, his imperturbable calm.”

A few steps away hung a similarly revealing painting of the great French composer Gabriel Fauré, one of Sargent’s most intimate friends. It conveys exactly what Aaron Copland, another admirer of Fauré’s music, had in mind when he spoke of his “restraint and classic sense of order…his delicacy, his reserve, his imperturbable calm.”

Am I wrong to see in this 1889 portrait a closeness of sympathy that might well have been made possible by the fact that Sargent could relate to Fauré on a musician-to-musician basis? He was, after all, an amateur pianist of very considerable accomplishment who was technically able enough to play duets with no less distinguished a partner than Arthur Rubinstein. Percy Grainger, who knew Sargent well, testified both to his pianistic skills and to his serious interest in Fauré’s music:

To hear Sargent play the piano was indeed a treat, for his pianism had the manliness and richness of his painting, though, naturally, it lacked that polished skillfulness that comes only with many-hourly daily practice spread over many years. He delighted especially in playing his favorite, Fauré…he bestowed upon the music of Gabriel Fauré the greatest depth and intensity of his musical admiration and devotion.

Another of his subjects, the American composer Charles Martin Loeffler, recalled that “[i]f he didn’t play all the right notes, he played the right wrong notes…a sign of true musicianship.” (Nathan Milstein said the same thing about George Balanchine’s slapdash but intensely musical piano playing.)

Two weeks ago Mrs. T and I paid a visit to Pittsburgh’s Carnegie Museum of Art, where we saw Arrangement in Black, Whistler’s portrait of Pablo de Sarasate, the the Spanish violinist-composer. Sarasate’s 1904 recordings, mostly of his own music, are played in the same gallery where “Arrangement in Black” is hung. I wonder whether anybody at the Met ever considered the possibility of playing Fauré’s piano-roll recordings in close proximity to his portrait? It might well have been illuminating to hear his 1910 performance of the Seventh Nocturne while mulling over what Sargent made of him:

It might also have been equally illuminating to view Sacha Guitry’s 1914 silent film of Claude Monet at work on a water-lily canvas after having looked at the two Sargent portraits of Monet that were on display:

To be sure, I don’t find Sargent’s exceedingly formal 1887 head of Monet to be especially penetrating. It shows us the public Monet, not the man within, and I can’t say that I’m very interested in the solid bourgeois fellow that I see therein. He conceals far more than he reveals.

But “Claude Monet Painting by the Edge of a Wood,” painted two years earlier, is something else again, a plein air study of the artist at work that has the freedom and immediacy of one of Sargent’s watercolors. The man in this painting is the same man that Guitry captured on camera, a quarter-century younger but surely identical in his unswerving intensity of focus. (You can tell that he isn’t distracted in the least by the presence of a female companion!)

But “Claude Monet Painting by the Edge of a Wood,” painted two years earlier, is something else again, a plein air study of the artist at work that has the freedom and immediacy of one of Sargent’s watercolors. The man in this painting is the same man that Guitry captured on camera, a quarter-century younger but surely identical in his unswerving intensity of focus. (You can tell that he isn’t distracted in the least by the presence of a female companion!)

Here, too, the wall label is worth reading, if a bit too deadpan to suit my tastes:

Sargent usually presented the sketches he made of friends and fellow artists to them as gifts, as was the tradition in artistic circles. This sketch of Claude Monet (1840–1926) is an exception. It remained with Sargent all his life and was in his studio when he died, along with several works by Monet that Sargent collected.

Monet is shown sitting at an easel painting a landscape outdoors. This portrait has assumed an importance in the history of Impressionism because it shows the French artist doing what he advocated, painting directly from nature. It certainly had a personal significance for Sargent, who greatly admired Monet, as it commemorates their artistic relationship.

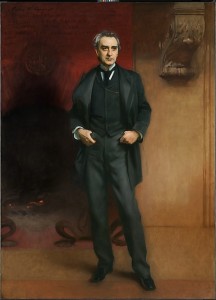

By the same token, I expect that a not-considerable number of the people who took time to look at “Edwin Booth” would have relished the opportunity to simultaneously hear Booth’s recorded voice. Though he was once famous enough to have been the subject of a 1955 Hollywood biopic, Booth is now remembered (if at all) as the brother of the man who shot Abraham Lincoln. Nevertheless, he was by all accounts the foremost American actor of the nineteenth century, and just as we can learn much about Sargent’s Monet from seeing the man himself at work, so can we learn at least as much about Sargent’s Booth by hearing the actual voice of his subject performing a monologue from Othello in 1892.

By the same token, I expect that a not-considerable number of the people who took time to look at “Edwin Booth” would have relished the opportunity to simultaneously hear Booth’s recorded voice. Though he was once famous enough to have been the subject of a 1955 Hollywood biopic, Booth is now remembered (if at all) as the brother of the man who shot Abraham Lincoln. Nevertheless, he was by all accounts the foremost American actor of the nineteenth century, and just as we can learn much about Sargent’s Monet from seeing the man himself at work, so can we learn at least as much about Sargent’s Booth by hearing the actual voice of his subject performing a monologue from Othello in 1892.

And what of Sargent himself? His infrequent self-portraits are as opaque as the written record of his life, which sheds little light on the man within, least of all on his sexuality, the aspect of human personality with which most of us are mainly obsessed nowadays. Given his passionate interest in music, that least corporeal of the arts, it’s tempting to assume that he was asexual.

On the other hand, certain of his paintings have long suggested otherwise, at least to me, and to look at “Young Woman with a Black Skirt” is surely to doubt that he was entirely unresponsive to the call of the flesh. Perhaps he was merely a camera, recording but not feeling, and perhaps it is foolishly romantic of me to suppose otherwise…but I do.

On the other hand, certain of his paintings have long suggested otherwise, at least to me, and to look at “Young Woman with a Black Skirt” is surely to doubt that he was entirely unresponsive to the call of the flesh. Perhaps he was merely a camera, recording but not feeling, and perhaps it is foolishly romantic of me to suppose otherwise…but I do.

As I drove back to Connecticut and Mrs. T after seeing Fool for Love and dining with Zephyr, I thought deeply about Sargent and his portraits—as well as more personal matters. More and more of late I find myself wondering just how much longer I’ll want to stay in New York. I’ve lived here, after all, for thirty years, long enough to have grown tired of the ceaseless exasperations that are an inescapable part of life in Manhattan, and I’ve traveled enough in those same thirty years to know that there is no shortage of other places that are full of their own satisfactions. But as I thought back on the hectic weekend just past—an improvised visit to the greatest museum in America, a pair of back-to-back Broadway matinees, the company of a much-loved friend—I realized that it wouldn’t be so simple to turn my back on the city that has now been my home for half of my life.

Do I love New York? After a fashion. Certainly I love what’s in New York, my friends above all. But there are times when my love extends beyond the contents of the city to the city itself. As I wrote in this space three years ago:

To be sure, it’s a bumpy, awkward kind of love, and I’ll always be a small-town boy at heart. Nor would it surprise me in the least if I were to pull up stakes one day and move. But by now I’ve lived in Manhattan longer than anywhere else, and should I ever move away, I know I’ll leave a not-so-small piece of my heart behind.

I still feel that way. Sometimes.

* * *

To order the catalogue of Sargent: Portraits of Artists and Friends, go here.

William Stromberg and the Moscow Symphony perform a suite from Bernard Herrmann’s score for Prince of Players, Philip Dunne’s film biography of Edwin Booth, in which Booth was played by Richard Burton: