Mrs. T and I are in Pittsburgh to see a play. Our last visit here took place four years ago, when we flew out to catch a rare revival of Alan Ayckbourn’s House and Garden, then drove back to Connecticut by way of the Jersey Shore. This trip, by contrast, is more tightly focused (we’re flying in and out) and much more static, thus giving us a fair amount of extra time to look around town.

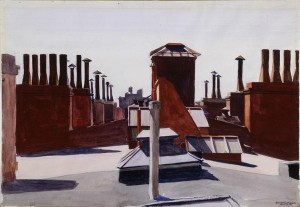

On Saturday we went to the Carnegie Museum of Art, which impressed us in 2011 and lured us back this time with a single-gallery show called CMOA Collects Edward Hopper consisting of the seventeen works by Hopper that are in the museum’s permanent collection. Most are etchings, including handsome impressions of Night Shadows and The Evening Wind, Hopper’s two best-known prints, but we were also much taken with a 1926 watercolor called Roofs, Washington Square that was new to both of us.

On Saturday we went to the Carnegie Museum of Art, which impressed us in 2011 and lured us back this time with a single-gallery show called CMOA Collects Edward Hopper consisting of the seventeen works by Hopper that are in the museum’s permanent collection. Most are etchings, including handsome impressions of Night Shadows and The Evening Wind, Hopper’s two best-known prints, but we were also much taken with a 1926 watercolor called Roofs, Washington Square that was new to both of us.

We went through the Hopper exhibition twice. In between we spent an hour and a half looking at the rest of the museum. Most of the pieces that we saw weren’t on display in 2011, and most of the ones that we liked best (including the Hoppers) were small. Possibly because I’ve spent my adult life living in apartments, I have a special love for small paintings and prints, in which the essence of an artist’s style can often be seen in highly compressed form. This is especially true of Berthe Morisot’s Young Girl with a Cat (Julie Manet), an 1888 drypoint that I coveted every bit as much as I did the CMA’s gorgeous copy of “Night Shadows.”

We went through the Hopper exhibition twice. In between we spent an hour and a half looking at the rest of the museum. Most of the pieces that we saw weren’t on display in 2011, and most of the ones that we liked best (including the Hoppers) were small. Possibly because I’ve spent my adult life living in apartments, I have a special love for small paintings and prints, in which the essence of an artist’s style can often be seen in highly compressed form. This is especially true of Berthe Morisot’s Young Girl with a Cat (Julie Manet), an 1888 drypoint that I coveted every bit as much as I did the CMA’s gorgeous copy of “Night Shadows.”

Morisot tends to get short shrift in discussions of the French impressionists, no doubt in part because she was a woman but also because of the soft-spoken intimacy of her work. The CMA also owns a spectacular Monet water-lily panel in front of which Mrs. T and I lingered, but we came back to “Young Girl with a Cat” twice, and I felt even more strongly on a second viewing that I could look at it every day. Aside from its sheer elegance of execution, I delighted in the sharp features of the young girl portrayed therein. If there is such a thing as a quintessentially French face, Julie Manet had one, and Morisot, her mother, managed to catch it on the etching plate.

Two other small paintings held my eye on Saturday. One was John Constable’s The Washing Line, which reminded me of Our Girl in Chicago, who first introduced me to Constable long ago. It is, like so many of Constable’s best paintings, a cloud study, and the CMA’s online catalogue describes it concisely and well:

Two other small paintings held my eye on Saturday. One was John Constable’s The Washing Line, which reminded me of Our Girl in Chicago, who first introduced me to Constable long ago. It is, like so many of Constable’s best paintings, a cloud study, and the CMA’s online catalogue describes it concisely and well:

The view depicted here is thought to be from an upper window of Constable’s home at No. 2 Lower Terrace, Hampstead, near London….In this tiny view of the family’s laundry drying in the garden, the sky provides the even illumination typical of an overcast day, and the sun is nowhere in sight.

I became interested in Constable’s sky studies after seeing a 2004 gallery show that billed itself as “the first sky studies show by John Constable in the United States.” The gallery in question is long gone, its owner (whom I liked very much) having turned out to be a big-league art thief. He is presently doing time in a medium-security prison where one of his fellow inmates was a popular rapper. As for my passion for Constable’s cloud paintings, it remains as strong as ever—though not enough to steal one of them!

We also relished Marsden Hartley’s Robin, a painting from the early Forties that is presently hanging next to a pair of larger and more characteristic canvases by Hartley. They’re both show-stoppers, but once again it was the smaller piece that spoke most eloquently to us. When you collect art, you very often find yourself judging it in terms of what you can envision hanging in your home. It happens that Mrs. T and I are the proud owners of one of Hartley’s lithographs, and it isn’t hard to see “Robin” hanging next to our prized copy of “Apples on Table.”

We also relished Marsden Hartley’s Robin, a painting from the early Forties that is presently hanging next to a pair of larger and more characteristic canvases by Hartley. They’re both show-stoppers, but once again it was the smaller piece that spoke most eloquently to us. When you collect art, you very often find yourself judging it in terms of what you can envision hanging in your home. It happens that Mrs. T and I are the proud owners of one of Hartley’s lithographs, and it isn’t hard to see “Robin” hanging next to our prized copy of “Apples on Table.”

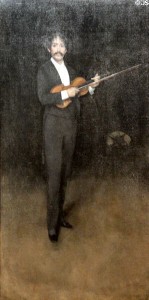

On the other hand, I can’t possibly imagine owning our favorite painting of the day, Whistler’s Arrangement in Black: Portrait of Señor Pablo de Sarasate, a full-length portrait of the celebrated Spanish violinist-composer for which the only possible word is spectacular. You’d have to live somewhere far more imposing than a two-bedroom Upper Manhattan apartment to hang such a painting with the éclat it merits.

In addition to being reviewed by George Bernard Shaw in 1889 and mentioned in Edith Wharton’s The Age of Innocence and Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s “The Red-Headed League,” Sarasate wrote himself into the book of life by cutting ten 78 sides in 1904, four years before he died. Accordingly, the CMA has installed a loudspeaker behind “Arrangement in Black” and plays his antique records on an endless loop. I suppose some connoisseurs might find the resulting effect vulgar, but it thrilled Mrs. T and me to the marrow.

In addition to being reviewed by George Bernard Shaw in 1889 and mentioned in Edith Wharton’s The Age of Innocence and Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s “The Red-Headed League,” Sarasate wrote himself into the book of life by cutting ten 78 sides in 1904, four years before he died. Accordingly, the CMA has installed a loudspeaker behind “Arrangement in Black” and plays his antique records on an endless loop. I suppose some connoisseurs might find the resulting effect vulgar, but it thrilled Mrs. T and me to the marrow.

It’s been a while since either of us went to a museum, and while that’s not an accurate index of the place of art in our lives—you don’t go to the trouble of acquiring three dozen carefully chosen prints and paintings unless you’re serious about it—we both came away from the CMA determined to spend more time making the rounds. On the other hand, we said the same thing after seeing the Paul Taylor Dance Company in Florida this past February, yet we haven’t gone to any dance performances since then. It seems there’s only so much spare time in a human life, and I find that I want to spend more and more of mine staying at home with Mrs. T. In any case, the fewer things you see, the more they mean to you.

To be sure, I didn’t feel that way back in my boulevardier days. Very likely I shouldn’t have: to everything there is a season. For me the time has come to reap the harvest of decades of looking and listening. Different seasons may follow—or not. But whatever the future has in store for me, I can’t imagine that my once-inexhaustible appetite for the new has abated other than temporarily.

Rimbaud said it:

Enough seen. The vision was encountered under all skies.

Enough had. Noises of cities, in the evening, and in the sunshine, and always.

Enough known. The pauses of life—O Sounds and Visions!

Departure into new affection and new noise!

It will be interesting to find out what new noises still await me as I prepare to cross the sixtieth meridian.

* * *

Pablo de Sarasate plays his “Caprice Basque,” recorded in London in 1904: