On Friday I drove from Connecticut to Niagara-on-the-Lake, Ontario, home of the Shaw Festival, about which I’ll be writing in Friday’s Wall Street Journal. I made the seven-hour trip by myself, since Mrs. T was worn out from our recent travels and so didn’t feel up to accompanying me. The two of us had been more or less inseparable for the past few weeks, and when we travel in tandem, we tend to chatter nonstop about everything under the sun. Suspecting that I might find the day-long drive more than a little bit tedious in her absence, I took care to pack a more than usually enticing selection of compact discs for purposes of diversion en route.

At first I was content to watch the world go by without benefit of soundtrack, but by the time I reached the outskirts of Albany, I was sorely in need of distraction. Stone-hard country music sounded just right to me, so I pulled out a two-disc anthology

At first I was content to watch the world go by without benefit of soundtrack, but by the time I reached the outskirts of Albany, I was sorely in need of distraction. Stone-hard country music sounded just right to me, so I pulled out a two-disc anthology

of recordings by the Louvin Brothers, fired up the CD player, slipped Handpicked Songs 1955-1962 into the slot, and found myself listening to a gospel song written in 1871 that reminded me forcibly of a half-forgotten aspect of my lost youth.

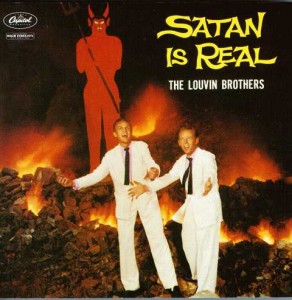

I last had occasion to write about the Louvin Brothers in a 2012 Wall Street Journal “Sightings” column, apropos of the publication of Satan Is Real: The Ballad of the Louvin Brothers, a memoir by Charlie Louvin that is named after their most celebrated album:

Like many sibling acts, they were a match made in hell, so much so that Ira Louvin’s violent, alcohol-fueled temper finally led Charlie, his younger brother, to break up the duo in 1963, two years before Ira died in a car crash. But you’d never have guessed it from hearing them sing together, for their high, hard-bitten voices wound round one another in harmonies so closely woven that you couldn’t always tell which brother was singing what part….

Flannery O’Connor observed in 1960 that “while the South is hardly Christ-centered, it is most certainly Christ-haunted.” Ira Louvin, who could never reconcile his deep-seated religious convictions with his fleshly urges, would have known exactly what she was talking about. To listen to a Louvin Brothers song like “Are You Afraid to Die” is to be left in no doubt whatsoever that Ira was at least as Christ-haunted as any of O’Connor’s fictional characters. According to Charlie, Ira believed that he had been called by God to preach the gospel, but was incapable of fulfilling his destiny: “It haunted him that he didn’t do what he was put here on this earth to do.”

You can hear exactly what Charlie Louvin was talking about in their performance of Almost Persuaded, whose doleful lyrics leave the listener in no possible doubt that the unnamed sinner at whom they are aimed is in grave and imminent danger of spending eternity in the hands of an extremely angry God:

You can hear exactly what Charlie Louvin was talking about in their performance of Almost Persuaded, whose doleful lyrics leave the listener in no possible doubt that the unnamed sinner at whom they are aimed is in grave and imminent danger of spending eternity in the hands of an extremely angry God:

“Almost persuaded,” harvest is past!

“Almost persuaded,” doom comes at last;

“Almost” cannot avail;

“Almost” is but to fail!

Sad, sad that bitter wail—

“Almost—but lost!”

Needless to say, the Louvin Brothers sing it exquisitely well—they sang everything exquisitely well—and you don’t have to believe in anything more than the ineffable beauty of a gleaming high note to relish their performance. But it so happens that I was raised a Southern Baptist, and as I listened to “Almost Persuaded,” I was put irresistibly in mind of the Sunday-morning “altar calls” in the Baptist churches of Smalltown, U.S.A., during which the preacher invited “unsaved” members of the congregation to come down the aisle and get right with God as their fellow worshippers waited patiently with heads bowed. These often-protracted exhortations were invariably accompanied by a slower-than-slow hymn, and I can’t imagine why “Almost Persuaded” never made the cut at my church, it being a quintessential example of the altar-call genre at its most ominously imploring.

Having whiled away the better part of a nostalgic afternoon listening to Charlie and Ira as I motored west through rural New York, I decided that a change of key was in order, so I put on the original-cast album of Stephen Sondheim’s A Little Night Music, a musical whose songs portray sex and its discontents with a knowing worldliness that has nothing whatsoever in common with “Almost Persuaded” save for the fact that they, too, are in three-quarter time.

Having whiled away the better part of a nostalgic afternoon listening to Charlie and Ira as I motored west through rural New York, I decided that a change of key was in order, so I put on the original-cast album of Stephen Sondheim’s A Little Night Music, a musical whose songs portray sex and its discontents with a knowing worldliness that has nothing whatsoever in common with “Almost Persuaded” save for the fact that they, too, are in three-quarter time.

Regular readers of this blog may recall that I recently saw and reviewed an excellent regional revival of Sondheim’s Company. It set me to thinking about how Jonathan Tunick’s up-to-the-minute 1970 orchestrations for that hugely influential show have long since acquired a near-quaint patina (they now sound very much like the kind of pit-band pop-rock you might have heard on a TV variety show of the period) that is decidedly at odds with its still-fresh subject matter.

For this reason, I found myself paying closer-than-usual attention to the completely different way in which Tunick scored A Little Night Music three years later. The string-laden orchestrations are, to be sure, gorgeous and elegant, but with small-scale Sondheim productions being all the rage these days, a brainwave occurred to me: why doesn’t somebody arrange the orchestral parts to A Little Night Music for piano duet, in the manner of the Brahms Liebeslieder Walzer to which Sondheim was surely paying affectionate tribute when he included in the cast a quintet of what he called “Lieder Singers”? Not only would such an accompaniment be musically appropriate to the highest degree, but it would be wonderfully well suited to the needs of any company that longs to present an intimate staging of A Little Night Music in a very small theater.

As I listened, I spent the next forty-five minutes or so mentally rescoring the first nine numbers from A Little Night Music for piano, four hands, and by the time “A Weekend in the Country” had run its course, I was, much to my surprise, within spitting distance of Buffalo. Never has the drive from Connecticut to the Canadian border passed so quickly or pleasingly.

If you’ve ever wondered what kinds of things I think about when I’m by myself…well, that’s a pretty good example.

* * *

From the BBC Proms 2010 “Sondheim at 80” concert at the Royal Albert Hall, Simon Russell Beale, Daniel Evans, Maria Friedman, Caroline O’Connor, Julian Ovenden, and Jenna Russell sing “A Weekend in the Country,” the first-act finale of A Little Night Music, accompanied by David Charles Abell and the BBC Concert Orchestra. The orchestration is by Jonathan Tunick:

Two excerpts from George Balanchine’s Liebeslieder Walzer, choreographed in 1960 to Brahms’ Liebeslieder Walzer and Neues Liebeslieder Walzer, Opp. 52 and 65. This performance, originally telecast by the CBC on L’Heure du Concert in 1961, is danced by Jillana, Conrad Ludlow, and the other members of the original New York City Ballet cast: