One of the most striking things about Ron Howard’s Apollo 13 is the way in which Howard and the film’s designers sought to recreate on screen the lost world of America in the late Sixties. Nowadays we take that kind of thing for granted, but it was less common two decades ago, and much was made at the time of the fact that Howard made a point of showing (for instance) how so many of NASA’s real-life flight controllers smoked, not just when under extreme pressure but routinely.

One of the most striking things about Ron Howard’s Apollo 13 is the way in which Howard and the film’s designers sought to recreate on screen the lost world of America in the late Sixties. Nowadays we take that kind of thing for granted, but it was less common two decades ago, and much was made at the time of the fact that Howard made a point of showing (for instance) how so many of NASA’s real-life flight controllers smoked, not just when under extreme pressure but routinely.

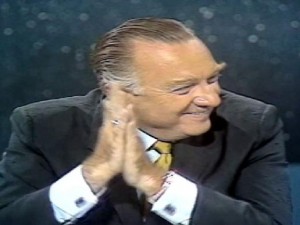

I watched Apollo 13 last week and was struck all over again by the sheer volume of chain-smoking that took place in Mission Control. What hit me even harder, though, was an actual piece of historical film footage. In the opening scene, we see a roomful of astronauts and their families celebrating in Houston as Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin land on the moon. The TV that they’re watching is tuned to CBS, and Walter Cronkite, who was anchoring the network’s coverage of the flight of Apollo 11, makes no secret of his delight at the mission’s success. “Oh, boy!” he cries in a tone that is not “objective” but unabashedly admiring.

I, too, was watching CBS that night, a thirteen-year-old boy unaware that he was witnessing a sea change in our national self-understanding. Having been a space buff throughout my childhood, it stood to reason that I should have been excited. But we were all on the same side on July 20, 1969, myself and my family and virtually the whole of America. Yes, the ties that bound us had been stretched to the breaking point by the assassinations of 1963 and 1968, and the Vietnam War was well on its way to snapping them. Yet we were still “we” on the night that Armstrong and Aldrin landed on the moon, just as we were “we” when, a few months later, the crew of Apollo 13 faced the imminent prospect of death in the silent chill of space. We believed in heroes then, just as we believed every word spoken on the air by Walter Cronkite, whose newscast my family watched each night after dinner.

This unanimity of national spirit is part of the point of Apollo 13, and I can’t help but wonder how it plays with younger viewers today, assuming they’ve seen the film. That’s not a safe assumption, seeing as how Apollo 13 was released in 1995. If you’re thirty years old, you weren’t yet born when Walter Cronkite retired, and you may well not even know his name, much less recognize his voice. You grew up in a very different country from the America of my youth, a land in which the phrase “common culture” was not in common use only because everybody took its existence for granted.

This unanimity of national spirit is part of the point of Apollo 13, and I can’t help but wonder how it plays with younger viewers today, assuming they’ve seen the film. That’s not a safe assumption, seeing as how Apollo 13 was released in 1995. If you’re thirty years old, you weren’t yet born when Walter Cronkite retired, and you may well not even know his name, much less recognize his voice. You grew up in a very different country from the America of my youth, a land in which the phrase “common culture” was not in common use only because everybody took its existence for granted.

I’ve written a lot, here and elsewhere, about what it was like to grow up under the aspect of a common national culture. Now Charles Murray has published an extremely interesting essay in Commentary called “The United States of Diversity” in which he argues that America’s postwar cultural unanimity was an aberration from the historical norm:

Movies were ubiquitous by the beginning of World War I, and most American homes had a radio by the end of the 1920s. These new mass media introduced a nationally shared popular culture, and one to which almost all Americans were exposed. Given a list of the top movie stars, the top singers, and the top radio personalities, just about everybody younger than 60 would not only have recognized all their names but have been familiar with them and their work.

After the war, television spread the national popular culture even more pervasively. Television viewers had only a few channels to choose from, so everyone’s television-viewing overlapped with everyone else’s. Even if you didn’t watch, you were part of it—last night’s episode of I Love Lucy was a major source of conversation around the water cooler.

In these and many other ways, the cultural variations that had been so prominent at the time of World War I were less obvious by the time the 1960s rolled around. A few cities remained culturally distinct, and the different regions continued to have some different folkways, but only the South stood out as a part of the country that marched to a different drummer, and the foundation of that distinctiveness, the South’s version of racial segregation, had been cracked by the Civil Rights Act of 1964. In December 1964, Lyndon Johnson evoked his mentor Sam Rayburn’s dream, expressed in 1913, of an America “that knows no East, no West, no North, no South.” Johnson was giving voice to a sentiment that seemed not only an aspiration but something that the nation could achieve once the civil-rights movement’s triumph was complete….

Half a century after Johnson’s dream of a geographically and culturally homogeneous America, the United States is at least as culturally diverse as it was at the beginning of World War I and in some respects more thoroughly segregated than it has ever been. Today’s America is once again a patchwork of cultures that are different from one another and often in tension.

I’ve been thinking about Murray’s essay since I saw Apollo 13. One of the conclusions I’ve reached is that America’s “national” high-art forms, partly because of the decline of the national media and partly because of the country’s sheer size, are well on their way to becoming purely local. Lest we forget, “American theater” used to mean theater in New York, period. That’s not true anymore, which helps to explain why the ratings for the annual Tony Awards telecast have been plummeting for years. And just as our regional theaters are now identical to Broadway in seriousness and accomplishment, so is Broadway itself turning into just another theatrical “region,” no better and no worse in artistic quality—and scarcely more influential—than, say, Chicago or San Francisco or Washington, D.C.

I don’t bemoan this development. I think it’s probably healthier for the arts in America, and I’m sure that it’s inevitable, and thus not to be lamented other than out of nostalgia. Still, I can’t help but be nostalgic for the Broadway that used to be, even though I experienced very little of it at first hand. For me it is all of a piece with the space program and Walter Cronkite and CBS itself, and that is one of the reasons why I miss it.

Of course I know we’re better off living in a land whose culture is no longer dominated by the gatekeepers of Mad Men-era Manhattan. But as I wrote when David Brinkley, Cronkite’s longtime competitor, died in 1997:

Of course I know we’re better off living in a land whose culture is no longer dominated by the gatekeepers of Mad Men-era Manhattan. But as I wrote when David Brinkley, Cronkite’s longtime competitor, died in 1997:

I miss the slow-moving America of my small-town youth, back when the word “everybody” was more than an abstraction. Red Skelton and Carol Burnett, Jack Paar and Johnny Carson, What’s My Line? and I’ve Got a Secret: All are gone and few remembered, and none has been replaced. TV has become yet another instrument of social fragmentation, an anteroom to the World Wide Web in which we sit in separate cubicles, sovereign monads reigning over gated communities of the mind. Intelligent people who call themselves conservatives tell me this is progress, and I might believe them if I believed in progress. Instead, I surf the Web in search of tiny firms that sell flickering kinescopes of old game shows, and note with sadness the passing of the long-forgotten giants of the small screen. I wonder, too, what future encounters with their multicultural pasts will cause my brightly ironic Gen-X friends to suddenly start thinking of themselves as Americans. Will they remember Seinfeld the way I remember David Brinkley? Somehow I doubt it.

I still do, which is why Apollo 13 continues to move me so deeply. If, like me, you had a happy childhood, you will never be able to ignore nostalgia’s siren call, no matter how determined you are to live in the moment. You don’t have to believe that something was wholly good—or even mostly good—to miss it when it’s gone.

* * *

Walter Cronkite describes the Apollo 11 launch and moon walk on CBS in July of 1969: