• Anthony Powell’s A Dance to the Music of Time is full of seemingly random observations about life whose general applicability causes them to leap off the page. Here are two that come to mind.

The first, made by Hugh Moreland, a composer-conductor of lively mind and depressive temperament, is from The Kindly Ones:

The arts derive entirely from taking decisions. That is why they make such unspeakably burdensome demands on all who practice them. Having taken the decisions music requres, I want to be free of all others.

I know what Moreland means. To be a critic of the arts is to spend the whole of your professional life making decisions about the merits of what you see and hear. In a sense, it’s all you do. As a result, I tend when “off duty” to be quite easygoing about quotidian matters of taste. To take just one example, I’d be more than happy (as Moreland was) to let Mrs. T choose all of the restaurants at which we go out to eat.

Alas, my line of work has conditioned me not only to be decisive but to maintain meticulous professional habits—I never come late to anything—and it is the evident destiny of such folk to end up serving as the designated drivers for everybody else in the world. As I noticed during the long-ago days when I had a nine-to-five newspaper job, any writer who also has managerial skills will quickly find himself under unremitting pressure to become an editor. It doesn’t matter how talented a writer he is—it’s harder to find good managers than good writers. I suspect that all of life is like that.

The second observation, made by Nick Jenkins, the narrator and Powell’s fictional alter ego, is from The Valley of Bones:

The second observation, made by Nick Jenkins, the narrator and Powell’s fictional alter ego, is from The Valley of Bones:

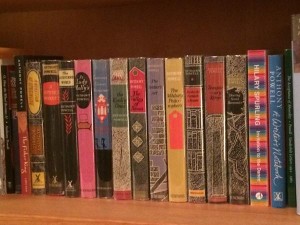

I was impressed for the ten thousandth time by the fact that literature illuminates life only for those to whom books are a necessity. Books are unconvertible assets, to be passed on only to those who possess them already.

Here, too, I found this remark to have the force of revelation. To be sure, most of my friends are avid readers, and I dare say that a handful of them might actually go along with Logan Pearsall Smith, who claimed to prefer reading to life. On the other hand, I’ve also been close to a few people who never read for pleasure, and when I was a professional musician, I knew a considerable number of otherwise smart and sensitive artists to whom books were unimportant. It would never occur to such folk to look to a novel in the hope of finding illumination, much less delight—and I have a feeling that their numbers are increasing.

Indeed, I think it possible (if unlikely) that I will live to see an America in which great literature has no cultural purchase whatsoever. I wonder what such a country would be like. Ray Bradbury tried to sketch it in Fahrenheit 451:

With school turning out more runners, jumpers, racers, tinkerers, grabbers, snatchers, fliers, and swimmers instead of examiners, critics, knowers, and imaginative creators, the word “intellectual,” of course, became the swear word it deserved to be. You always dread the unfamiliar.

For some Americans, of course, that new world has already taken shape, and there are those who even claim to find it desirable. But of course they don’t really believe in the desirability of illiteracy. What they want is power—and they’re getting it.