An old college friend of mine who visited Los Angeles with her husband last week made a special point of going to see a performance of Satchmo at the Waldorf, my first play, which closed there yesterday. “I’m so proud of you,” she wrote to me afterward, adding that John Douglas Thompson’s performance had “brought us to tears.” What touched me most about this message was that it came from someone who knew me when I was young. Until then, the only people to have seen Satchmo who’d known me before I moved to New York from Kansas City, where I lived from 1975 to 1983, were my brother, sister-in-law, and niece.

That move was the great divide of my life, far greater and more consequential than my departure from Smalltown, U.S.A., in the fall of 1974. After an unhappy and abortive semester at St. John’s College in Annapolis, I transferred to William Jewell College, a school not far from Kansas City, where I felt completely at home. Many of the friendships that I forged in Kansas City remained alive when I moved from there to Urbana, Illinois, in 1983. But once I left the Midwest for good two years later, I left my friends behind, and my subsequent contacts with them would be sporadic at best.

That move was the great divide of my life, far greater and more consequential than my departure from Smalltown, U.S.A., in the fall of 1974. After an unhappy and abortive semester at St. John’s College in Annapolis, I transferred to William Jewell College, a school not far from Kansas City, where I felt completely at home. Many of the friendships that I forged in Kansas City remained alive when I moved from there to Urbana, Illinois, in 1983. But once I left the Midwest for good two years later, I left my friends behind, and my subsequent contacts with them would be sporadic at best.

This break wasn’t deliberate. I loved Smalltown and Kansas City, and I Ioved the friends I made in both places. But it happened that none of the members of my family lived in or near Kansas City, making it all but inevitable that my visits there would grow increasingly infrequent. In time they ceased entirely: I didn’t go to Kansas City at all between 2000 and 2009, when I went there to review a play for The Wall Street Journal, an experience that I found to be overwhelmingly moving. Even then, though, I didn’t seek out anyone I knew.

As I explained in this space immediately after the fact:

I still know a number of people in Kansas City and its environs, and it would have taken no more than a half-dozen phone calls for me to come up with someone to share every meal I ate there last weekend. Instead I kept my presence strictly to myself. It wasn’t that I didn’t want to see my old friends–I miss them very much–but I knew that I urgently needed to spend some time alone with the past.

I’ve since gotten back in touch with several of the people whom I knew in high school and college, a process much facilitated by the coming of Facebook, and I’ve visited Kansas City several more times, always with the greatest of pleasure. I went so far as to take Mrs. T there in 2011. (She loved it.) Alas, my ties to the past continue to live mostly in memory. Not only do I know no one in New York who comes from Missouri, but I’ve made most of my present-day friends in the past decade and a half. Except for the members of my immediate family and Our Girl in Chicago, whom I met in 1988, there is only one person whom I now see other than occasionally whose friendship with me dates from my earliest years in New York, and none whom I knew prior to 1985.

I’ve since gotten back in touch with several of the people whom I knew in high school and college, a process much facilitated by the coming of Facebook, and I’ve visited Kansas City several more times, always with the greatest of pleasure. I went so far as to take Mrs. T there in 2011. (She loved it.) Alas, my ties to the past continue to live mostly in memory. Not only do I know no one in New York who comes from Missouri, but I’ve made most of my present-day friends in the past decade and a half. Except for the members of my immediate family and Our Girl in Chicago, whom I met in 1988, there is only one person whom I now see other than occasionally whose friendship with me dates from my earliest years in New York, and none whom I knew prior to 1985.

More than anything else, the absence from my present life of my older friends is an accident of geography. America is a big country, and long-distance friendships are even harder to sustain than long-distance romances. But whatever the reason, this absence has deprived me of an experience that Robert Penn Warren described accurately and beautifully in All the King’s Men:

The Friend of Your Youth is the only friend you will ever have, for he does not really see you. He sees in his mind a face that does not exist anymore, speaks a name–Spike, Bud, Snip, Red, Rusty, Jack, Dave–which belongs to that now nonexistent face but which by some inane doddering confusion of the universe is for the moment attached to a not happily met and boring stranger. But he humors the drooling doddering confusion of the universe and continues to address politely that dull stranger by the name which properly belongs to the boy face and to the time when the boy voice called thinly across the late afternoon water or murmured by a campfire at night or in the middle of a crowded street said, “Gee, listen to this–‘On Wenlock Edge the wood’s in trouble; His forest fleece the Wrekin heaves–’” The Friend of Your Youth is your friend because he does not see you anymore.

And perhaps he never saw you. What he saw was simply part of the furniture of the wonderful opening world. Friendship was something he suddenly discovered and had to give away as a recognition of and payment for the breathlessly opening world which momently divulged itself like a moonflower. It didn’t matter a damn to whom he gave it, for the fact of giving was what mattered, and if you happened to be handy you were automatically endowed with all the appropriate attributes of a friend and forever after your reality is irrelevant. The Friend of Your Youth is the only friend you will ever have, for he hasn’t the slightest concern with calculating his interest or your virtue.

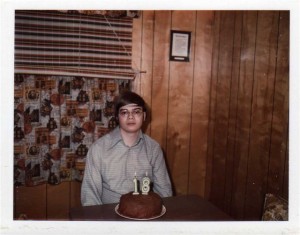

That’s why it meant so much to me to learn that a Friend of My Youth had seen Satchmo. In the days when Debbie and I knew one another well, I was still in the early stages of the slow process of becoming myself. Yes, I’d acted in a few plays—in fact, Debbie saw me on stage more than once, a thought that makes me cringe with retrospective embarrassment—but I had yet to start playing jazz professionally or write my first concert review or visit New York. If you’d told me back then that it was my destiny to move there, become a drama critic, and write a successful play of my own, I would have laughed in your face. My sense of possibilities had been cramped by my small-town upbringing, and the wonderful opening world of adulthood, with its infinitely wider horizons, had yet to fully open itself to me.

That’s why it meant so much to me to learn that a Friend of My Youth had seen Satchmo. In the days when Debbie and I knew one another well, I was still in the early stages of the slow process of becoming myself. Yes, I’d acted in a few plays—in fact, Debbie saw me on stage more than once, a thought that makes me cringe with retrospective embarrassment—but I had yet to start playing jazz professionally or write my first concert review or visit New York. If you’d told me back then that it was my destiny to move there, become a drama critic, and write a successful play of my own, I would have laughed in your face. My sense of possibilities had been cramped by my small-town upbringing, and the wonderful opening world of adulthood, with its infinitely wider horizons, had yet to fully open itself to me.

Now I live there, and I don’t regret doing so. “I feel the temptation to live in the past, but one can truly live only in the moment,” I wrote in this space in 2003. I believe that as much today as I did then. And yet…when I last had occasion to quote these words eleven months ago, I added this qualification: “To accept the inescapability of the present is not to deny the pull of the past. You can have, and love, both.”

It is precisely because I love them both that I was so moved by Debbie’s message. When she sat down to watch Satchmo in Los Angeles, my past and present reached out across the long years to join hands with one another. I only wish I could have been there to watch. I doubt she would have been the only one crying.

* * *

Joe Turner and His Fly Cats perform “Piney Brown Blues” in 1940: