• It hasn’t happened often, or recently, but from time to time I’ve been told things about good friends that I really, really didn’t want to know. None of them, fortunately, was bad enough to put me in mind of Somerset Maugham’s claim in Don Fernando that “I do not believe that there is any man, who if the whole truth were known of him would not seem a monster of depravity.” (Certainly Maugham himself qualified.) But when you learn that someone you know well has done something of which you strongly disapprove, it’s more than likely that your feelings about that person will be colored by that knowledge.

• It hasn’t happened often, or recently, but from time to time I’ve been told things about good friends that I really, really didn’t want to know. None of them, fortunately, was bad enough to put me in mind of Somerset Maugham’s claim in Don Fernando that “I do not believe that there is any man, who if the whole truth were known of him would not seem a monster of depravity.” (Certainly Maugham himself qualified.) But when you learn that someone you know well has done something of which you strongly disapprove, it’s more than likely that your feelings about that person will be colored by that knowledge.

Should this be so? I suppose it depends on the nature and gravity of the offense. I can’t imagine wanting to maintain a friendship with someone who had been definitively exposed as, say, a first-degree murderer or a child molester. On the other hand, I’m friendly with a certain number of people who have sundered or damaged marriages (sometimes their own, sometimes others) by committing adultery, about which I take a view not dissimilar to that of Frank Skeffington in The Last Hurrah: “Like most of his people, he did not regard it as one of the genial sins. It was perhaps the single offense with which he had never been charged, not even by opponents who were surely aware that it was the one charge which, if substantiated, could ruin him with the local electorate.” But while I generally incline to side with the offended party in such cases, I’ve lived long enough to know that even the best marriages are neither simple nor transparent. I don’t pretend to omniscience when it comes to other people’s lives—or, for that matter, anything else.

How stringent, then, should we be when it comes to scandalous revelations about the private lives of public figures? In the case of politicians, Mrs. T takes a firm live-and-let-live stance on sexual matters, but draws the line at corruption. I’m more rigorous, believing as I do that all politicians are guilty until proven innocent and that anything that causes a sitting pol to be cast out of office almost certainly serves the greater good ex hypothesi.

Artists, on the other hand, usually get a pass from me, at least as regards their professional lives. The case I invariably cite is that of Alfred Cortot, the greatest French pianist of the twentieth century, about whom I had occasion to write last year in The Wall Street Journal:

Artists, on the other hand, usually get a pass from me, at least as regards their professional lives. The case I invariably cite is that of Alfred Cortot, the greatest French pianist of the twentieth century, about whom I had occasion to write last year in The Wall Street Journal:

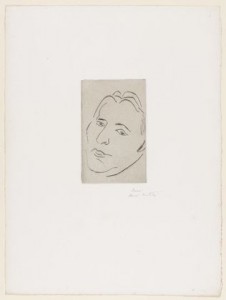

I recently paid a visit to “Matisse as Printmaker,” a touring show of Henri Matisse’s prints….One of the most striking prints in the show is a characterful 1927 drypoint called “The Pianist Alfred Cortot.” Cortot was the greatest of all French classical pianists, a recreative genius—no lesser word is strong enough—whose recorded performances of the music of Chopin, Schumann, Debussy and Ravel are incomparably beautiful. But he became a Nazi collaborator who served as Vichy’s High Commissioner of Fine Arts and performed in Hitler’s Germany, and that despicable fact will taint the memory of his artistry to the end of time.

I chose the word “taint” very carefully. I listen to Cortot’s recordings with the utmost pleasure, and I don’t think about his vicious conduct while they’re playing—yet I never think about Cortot himself without recalling with contempt how he conducted himself during the Occupation. As I’ve said on more than one occasion, the ability to make great art excuses no man his basic human responsibilities.

Up to now I’ve been stabbing around the word “hypocrisy” without ever striking it. On the one hand, I believe that hypocrisy is an essential social lubricant in whose absence the world would likely grind to a halt. On the other hand, there are certain kinds of hypocrisy that I regard as an absolute disqualification for public life. Nothing is more despicable than a judge who sends men to jail for doing what he himself does in private.

Which brings us, as all things seem to do nowadays, to the social media. I wonder how the Facebook-enabled young will feel about hypocrisy and its discontents, just as I wonder whether—or, more likely, how soon—they will come to regret their personal decisions to live their private lives in public. I remarked in this space the other day that I’m “old-fashioned enough to believe in the absolute necessity for a truly private life.” When I was being investigated by the White House preliminary to being appointed to the National Council on the Arts, I found it extraordinarily disagreeable to have to go downtown and be interrogated by an FBI agent. He was, to be sure, perfectly polite, but it’s a strange sensation to be asked to your face if you’ve ever done anything that might embarrass the President of the United States. Under such circumstances, the temptation to reply I should damned well hope so! is all but impossible to resist—though I resisted it.

Which brings us, as all things seem to do nowadays, to the social media. I wonder how the Facebook-enabled young will feel about hypocrisy and its discontents, just as I wonder whether—or, more likely, how soon—they will come to regret their personal decisions to live their private lives in public. I remarked in this space the other day that I’m “old-fashioned enough to believe in the absolute necessity for a truly private life.” When I was being investigated by the White House preliminary to being appointed to the National Council on the Arts, I found it extraordinarily disagreeable to have to go downtown and be interrogated by an FBI agent. He was, to be sure, perfectly polite, but it’s a strange sensation to be asked to your face if you’ve ever done anything that might embarrass the President of the United States. Under such circumstances, the temptation to reply I should damned well hope so! is all but impossible to resist—though I resisted it.

The truth, however, is that I’ve led a largely blameless life, and while I didn’t tell the agent everything I should have told him, the things I neglected to mention were about other people, not myself. I have precious few purely personal secrets, scarcely any of which are consequential. Embarrassing, yes, but for the most part what I keep to myself in this space and on Facebook and Twitter is almost entirely a function of the reflexive pudeur that comes with growing up in a small midwestern town.

Fortunately, my own well-developed sense of pudeur doesn’t stop me from appreciating the confidences of my livelier friends, or relishing the high-voltage gossip that is the stock in trade of anyone who works in the world of art. And so far as I know, none of my friends has ever done anything genuinely monstrous. Disappointing? That’s something else again—and I’ll readily admit to being far more judgmental in private than I allow myself to appear in public. But I judge myself at least as harshly as I do anyone else, and rightly or wrongly, I’ve never broken with a friend.

Horace said it: “It is right for him who asks forgiveness for his offenses to grant it to others.” So I do, and so should you—up to a point.

* * *

Alfred Cortot plays excerpts from Debussy’s Children’s Corner in 1938, accompanied by a sequence of tableaux staged and directed for the screen by Marcel L’Herbier: