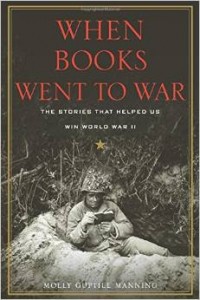

My monthly essay for the June issue of Commentary, whose occasion is the publication of Molly Guptill Manning’s When Books Went to War: The Stories That Helped Us Win World War II , can now be read on line. Here’s an excerpt.

My monthly essay for the June issue of Commentary, whose occasion is the publication of Molly Guptill Manning’s When Books Went to War: The Stories That Helped Us Win World War II , can now be read on line. Here’s an excerpt.

* * *

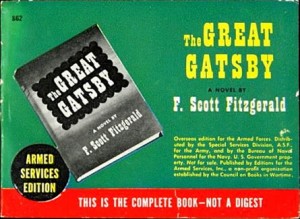

It’s said that two things about war are insufficiently appreciated by those who, like me, have not known it first-hand: 1) It is, when not terrifying, mostly dull, and 2) it is, like all human enterprises, subject to the operation of the law of unintended consequences. Few aspects of World War II better illustrate both of these points than the Armed Services Editions publishing project. Between 1943 and 1947, the U.S. Army and Navy distributed some 123 million newly printed paperback copies of 1,322 different books to American servicemen around the world. These volumes, which were given out for free, were specifically intended to entertain the soldiers and sailors to whom they were distributed, and by all accounts they did so spectacularly well. But they also transformed America’s literary culture in ways that their wartime publishers only partly foresaw—some of which continue to be felt, albeit in an attenuated fashion, to this day….

Starting from scratch, these civilians quickly managed to get large numbers of books into the hands of large numbers of grateful servicemen. Without their efforts, America’s soldiers and sailors would have found their wartime service to be even more cruelly burdensome than it was—and America’s authors and publishers would have faced a very different set of problems when the war ended and those servicemen returned home….

The story of the ASEs is told efficiently enough in When Books Went to War. But Manning is a lawyer, not a literary scholar, and she appears to have little or no awareness of their cultural context, thus making it impossible for her to interpret the project’s larger significance other than superficially. It is revealing, for instance, that the word “middlebrow” appears nowhere in When Books Went to War. Yet the most casual perusal of the list of books reprinted by the Council on Books in Wartime reveals that it reflected in every way the democratic assumptions of the middlebrow culture that dominated America throughout much of the 20th century. The vast popularity of the ASEs testifies to the strength of those assumptions.

The story of the ASEs is told efficiently enough in When Books Went to War. But Manning is a lawyer, not a literary scholar, and she appears to have little or no awareness of their cultural context, thus making it impossible for her to interpret the project’s larger significance other than superficially. It is revealing, for instance, that the word “middlebrow” appears nowhere in When Books Went to War. Yet the most casual perusal of the list of books reprinted by the Council on Books in Wartime reveals that it reflected in every way the democratic assumptions of the middlebrow culture that dominated America throughout much of the 20th century. The vast popularity of the ASEs testifies to the strength of those assumptions.

At the heart of middlebrow culture was the belief that high art was accessible to anyone who was willing to put in the effort to understand it, and that reading “serious” bestsellers such as Irving Stone’s Lust for Life or John P. Marquand’s The Late George Apley could serve as preparation for more ambitious ventures into great literature. For those servicemen who were already in the habit of reading for pleasure, the stateside counterpart of the ASEs was the Book-of-the-Month Club (which is mentioned only in passing in When Books Went to War). Both enterprises were essentially aspirational in their goals, both drew on the same wide-ranging pool of books, and both were broadly successful in elevating the literary tastes of those readers who made good use of them….

* * *

Read the whole thing here.