“He was gifted with the sly, sharp instinct for self-preservation that passes for wisdom among the rich.”

“He was gifted with the sly, sharp instinct for self-preservation that passes for wisdom among the rich.”

Evelyn Waugh, Scoop

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City

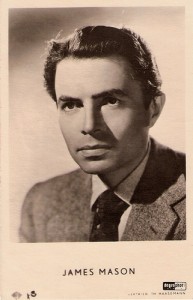

Rare are the dreams of childhood that come true at last, but one of mine, much to my surprise and delight, has actually realized itself, more or less, now that I’m on the brink of late middle age: I have a passably attractive speaking voice. No, it isn’t the dark-brown, gorgeously fine-grained James Mason-type voice for which I always longed in vain, nor do I have the floor-shaking chest resonance that I envy whenever I hear it. But as I listened to myself on the soundtrack of HBO’s Sinatra: All or Nothing at All the other night, I was reminded that I really do sound good when speaking into a microphone. Time has transposed me down a major third, and what was once a light baritone is now a smooth, slightly heavier bass-baritone, one that by all accounts is pleasing to the ear, especially when it’s electronically amplified.

Rare are the dreams of childhood that come true at last, but one of mine, much to my surprise and delight, has actually realized itself, more or less, now that I’m on the brink of late middle age: I have a passably attractive speaking voice. No, it isn’t the dark-brown, gorgeously fine-grained James Mason-type voice for which I always longed in vain, nor do I have the floor-shaking chest resonance that I envy whenever I hear it. But as I listened to myself on the soundtrack of HBO’s Sinatra: All or Nothing at All the other night, I was reminded that I really do sound good when speaking into a microphone. Time has transposed me down a major third, and what was once a light baritone is now a smooth, slightly heavier bass-baritone, one that by all accounts is pleasing to the ear, especially when it’s electronically amplified.

This midlife transformation reminds me of the one experienced by the fictional narrator of Hugh MacLennan’s The Watch That Ends the Night, who to his utter amazement became famous throughout Canada as a radio news commentator:

I’m not a man with much self-confidence and when I was young took it for granted that nobody respected me or paid me any attention. When I was young I was just another of those people who are around, for I had, and still have, a clumsy body of which I was never proud and when I was young I was timid. But living with Catherine had matured me a little and my work on the radio had taught me how to control my voice. I realized now—for I have learned to listen to my own voice as though it came from somebody else, I have learned what it sounds like from listening to play-backs in the studio—I realized now that it was resonant and steady.

Had I been born three-quarters of a century earlier, I, too, might have done well in radio. But I missed that boat long, long ago, and even if I’d tried to board it, the gelded voices that are favored on what is left of network radio are infinitely different from the ones that dominated the medium in the forgotten days of Ed Murrow and Eric Sevareid. We now prefer snarky pseudo-irony to calm authority. So instead of earning a living by talking into a microphone, I do it by sitting on the aisle and writing about what I see there, and save on rare occasions, the only people who hear my voice are the ones sitting next to me.

Had I been born three-quarters of a century earlier, I, too, might have done well in radio. But I missed that boat long, long ago, and even if I’d tried to board it, the gelded voices that are favored on what is left of network radio are infinitely different from the ones that dominated the medium in the forgotten days of Ed Murrow and Eric Sevareid. We now prefer snarky pseudo-irony to calm authority. So instead of earning a living by talking into a microphone, I do it by sitting on the aisle and writing about what I see there, and save on rare occasions, the only people who hear my voice are the ones sitting next to me.

I hope you don’t think I’m dissatisfied with my lot. Far from it! I am, however, perpetually puzzled by the yawning gap between what I am and what I expected to become. Here’s something I wrote a decade ago:

I was talking the other evening to a fellow critic seated behind me on the aisle of a Broadway theater. He’s eighty, and doesn’t look it, nor does he feel it. “I don’t feel a day over sixty-five,” he told me. “I keep waiting for all that wisdom that’s supposed to come with old age—but it hasn’t come yet.”

As for me, all I know is that nothing I imagined for myself when young has come to pass: everything is different, utterly so. I’m not a schoolteacher, not a jazz musician, not the chief music critic of a major metropolitan newspaper, not a syndicated columnist, not settled and secure. Nor am I the person I expected to be, calm and detached and philosophical: I still cry without warning, laugh too loud, lose my head and heart too easily, the same way I did a quarter-century ago. The person I was is the person I am, only older. Might that be wisdom of a sort?

Ten years later, my fellow critic is a reasonably spritely ninety years old, while I’m closing in fast on sixty. Like him, I wait in vain for wisdom and content. But I can claim for myself a deeply satisfying marriage and a life that continues to be full of happily unexpected developments, not the least of which is the pleasant fact that at long last, I have the voice I always wanted. It may not sound like James Mason, or even Claude Rains, but it’ll do.

* * *

James Mason and Jane Fonda appear as the celebrity contestants on a 1962 episode of Password, hosted by Allen Ludden:

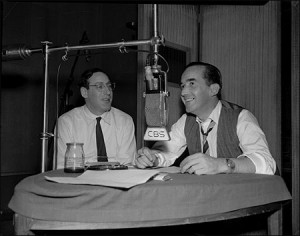

Edward R. Murrow introduces the first episode of This I Believe, a CBS radio series that aired from 1951 to 1955:

(To read Walker Percy’s description of This I Believe in The Moviegoer, go here.)

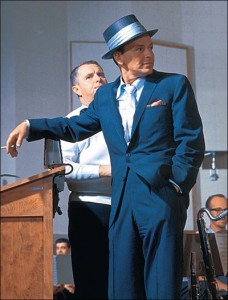

I watched both parts of Sinatra: All or Nothing at All, Alex Gibney’s four-hour-long documentary about the life and art of Frank Sinatra, last night. Entirely aside from the fact that I figured prominently in it, I thought it extraordinarily good, perhaps the best TV documentary about a musician made to date. To be sure, Gibney mostly showed us Sinatra from the singer’s own point of view and that of his family members—in particular his son, who has long fascinated me, and his first wife, who describes their failed marriage with arresting candor—but given that fact, All or Nothing at All still struck me as unusually balanced and forthright.

I watched both parts of Sinatra: All or Nothing at All, Alex Gibney’s four-hour-long documentary about the life and art of Frank Sinatra, last night. Entirely aside from the fact that I figured prominently in it, I thought it extraordinarily good, perhaps the best TV documentary about a musician made to date. To be sure, Gibney mostly showed us Sinatra from the singer’s own point of view and that of his family members—in particular his son, who has long fascinated me, and his first wife, who describes their failed marriage with arresting candor—but given that fact, All or Nothing at All still struck me as unusually balanced and forthright.

When the producers reached out to me last year, they assured me that they intended to concentrate on Sinatra the artist. They kept that promise: I was impressed by how clearly his absolute musical professionalism came across on screen. (I would have given a great deal to interview Sinatra, by the way, for nobody who knew anything about music seems ever to have done so at length, and the rare moments in All or Nothing at All when he speaks in specific terms about his craft are like flashbulbs going off in the dark.) At the same time, though, I was no less impressed with Gibney’s treatment of Sinatra’s private life, which I found to be honest but never salacious.

Needless to say, I was already well aware of the sharp difference between Sinatra’s cultivated singing voice and tough-guy speaking voice, but All or Nothing at All, which makes extensive use of revealing material drawn from private interview tapes, underlines it. That difference was and is a startlingly vivid symbol of the deep cleft in his personality, which was on view whenever he performed in public. I now feel even more strongly than before that the Sinatra of the recording studio was his best and truest self, whereas the presence of an audience too often tempted him to a vulgarity unworthy of his art. (This is something about which Mia Farrow speaks interestingly in All or Nothing at All.) On occasion, though, he succeeded in controlling that tendency, above all in the never-before-seen film of his 1971 “farewell” concert, which is the spine around which All or Nothing at All is built. It is the most revealing document in existence of Sinatra the performer. Even if the rest of the show weren’t as good as it is, it would have been worth seeing for that footage alone.

Needless to say, I was already well aware of the sharp difference between Sinatra’s cultivated singing voice and tough-guy speaking voice, but All or Nothing at All, which makes extensive use of revealing material drawn from private interview tapes, underlines it. That difference was and is a startlingly vivid symbol of the deep cleft in his personality, which was on view whenever he performed in public. I now feel even more strongly than before that the Sinatra of the recording studio was his best and truest self, whereas the presence of an audience too often tempted him to a vulgarity unworthy of his art. (This is something about which Mia Farrow speaks interestingly in All or Nothing at All.) On occasion, though, he succeeded in controlling that tendency, above all in the never-before-seen film of his 1971 “farewell” concert, which is the spine around which All or Nothing at All is built. It is the most revealing document in existence of Sinatra the performer. Even if the rest of the show weren’t as good as it is, it would have been worth seeing for that footage alone.

Incidentally, it was startling to hear Sinatra use four-letter words in All or Nothing at All. Of course I knew he talked that way, but it’s far different to hear him do it than merely to imagine him doing it. (I tried to give the audience a similar shock of recognition when I put the same kind of language in Louis Armstrong’s mouth in Satchmo at the Waldorf.)

Here are some other thoughts that occurred to me as I watched:

• I’m glad that Sinatra made movies—he could act fabulously well whenever it suited him—but most of them were an obvious waste of his time and talent. We would think the same of him today if he’d never made any of them, even From Here to Eternity, fine though it is. Moreover, Sinatra was hopeless as a TV host, for he was much too hot (in Marshall McLuhan’s sense) for the medium.

• Of all the Sinatra albums that never got recorded, I most regret the one that he wanted to make with the Oscar Peterson Trio. It might not have worked—he was never a true jazz singer—but I would have loved to hear it anyway. (If I’d been his producer, I would have put him in the studio with Jim Hall. That would have worked.)

• Of all the Sinatra albums that never got recorded, I most regret the one that he wanted to make with the Oscar Peterson Trio. It might not have worked—he was never a true jazz singer—but I would have loved to hear it anyway. (If I’d been his producer, I would have put him in the studio with Jim Hall. That would have worked.)

• Why did no one ever tell Sinatra how awful-looking his toupees were? I suppose they simply couldn’t get up the nerve.

• Two people whom I wish had been mentioned, however briefly, in All or Nothing at All are Billie Holiday (who, like Sinatra, was born a hundred years ago) and Mabel Mercer. He gave them both credit for inspiring his own art.

• It felt disorientingly strange to hear myself on the soundtrack of All or Nothing at All. Of course I knew who was talking, but I couldn’t quite grasp that it was me. (I felt the same sense of dissociation when I sat in the audience for the opening nights of Satchmo at the Waldorf and The Letter.) For what it’s worth, though, I liked what I had to say, and I’m proud to have been a part of this superlative show.

It happens that I’ve only written about Frank Sinatra at length twice, in 1995 and 1997, and I never thought seriously about writing a book about him. Now that I’ve seen All or Nothing at All, I almost wish I could.

* * *

Frank Sinatra sings “Angel Eyes” on The Frank Sinatra Timex Show in 1959. He closed his 1971 “farewell” concert with the same song, and made the same exit:

Art isn’t religion, but it has something important in common with religion: it’s a form of soulcraft. Souls can only be changed one by one, and each one is as supremely important as the next. Hence there are no small audiences, only small-souled artists. Blessed are the arts that can be experienced by a mere handful of people at a time, for theirs is the kingdom of beauty at its most intense and precious….

Read the whole thing here.

An old friend of mine who sings jazz for a living just sent me a freshly recorded sound file on which she performs a song that I love, Joni Mitchell’s “A Case of You.” I’ve known her voice for the better part of two decades now, and it was, I thought, entirely mature when I first heard it. Yet something has happened to her singing in the past few years. While her style hasn’t changed in any obvious way, it has become more powerfully expressive. That kind of transformation is often the fruit of long experience, which has the power to etch the human voice over time with the marks of suffering—and transcendence.

As I listened to my friend sing, I thought of the restaurant review that Anton Ego reads aloud (in the deliciously haughty voice of Peter O’Toole) at the end of Brad Bird’s Ratatouille. Ego is too often mistaken for an Addison DeWitt-type critic-killer, but in truth he is an aesthete of the highest possible seriousness who is all too aware of his own inability to create and thus profoundly respectful of those who, possessing that power, use it to the fullest. It is inexpressibly moving to hear him confess without self-pity that “the bitter truth we critics must face, is that in the grand scheme of things, the average piece of junk is probably more meaningful than our criticism designating it so,” and more moving still when he praises Remy and Colette for having cooked “an extraordinary meal…that rocked me to my core.”

As I listened to my friend sing, I thought of the restaurant review that Anton Ego reads aloud (in the deliciously haughty voice of Peter O’Toole) at the end of Brad Bird’s Ratatouille. Ego is too often mistaken for an Addison DeWitt-type critic-killer, but in truth he is an aesthete of the highest possible seriousness who is all too aware of his own inability to create and thus profoundly respectful of those who, possessing that power, use it to the fullest. It is inexpressibly moving to hear him confess without self-pity that “the bitter truth we critics must face, is that in the grand scheme of things, the average piece of junk is probably more meaningful than our criticism designating it so,” and more moving still when he praises Remy and Colette for having cooked “an extraordinary meal…that rocked me to my core.”

I never felt inadequate or frustrated when all I did was criticize the art of other people. I think this was because I tried to do so with a pure heart, seeking out opportunities to appreciate beautiful things rather than reveling in my power to smite the heathens. But I had spent several gratifying years as a professional bassist before becoming a full-time critic, and so I felt doubly blessed when I unexpectedly acquired in middle age the ability to write for the stage. I have no illusions about the significance of my late-blooming success as a playwright: as proud as I am of Satchmo at the Waldorf, I know that it’s small potatoes next to the plays of the supremely gifted writers whom it is my privilege to praise in the pages of The Wall Street Journal. Nevertheless, the fact that I somehow managed to write a new play of my own that gave pleasure to audiences cannot but have special meaning for a recovering musician like me who has never forgotten what it felt like to play jazz in public.

Robert Atkins, the author of Hand of God, which transfers to Broadway this week, recently gave an interview to the New York Times in which he said something about the experience of playwriting that I found striking:

It’s the most impossible thing in the world, but if you can do it, no one can say no to you. No one can say to you you’re wrong, because the entire audience—the room of 800, or 199, or 78 people experienced something. They laughed and they cried and they gasped and then they got up and they clapped. And no one—no academic, no father figure, can say to you that that didn’t happen. This is not academic, this is visceral, and that’s exciting. It’s sacred.

I’m sure my friend feels the same visceral sensation whenever she gets up in front of an audience to sing. And though my own performing days are long since ended, I find it almost as exciting to sit in a theater and watch in silence and awe as my words are spoken aloud by a great actor. I doubt I’ll ever come any closer to getting up on stage myself and playing jazz again, the way I used to do a million years ago—but that’s close enough.

I’m sure my friend feels the same visceral sensation whenever she gets up in front of an audience to sing. And though my own performing days are long since ended, I find it almost as exciting to sit in a theater and watch in silence and awe as my words are spoken aloud by a great actor. I doubt I’ll ever come any closer to getting up on stage myself and playing jazz again, the way I used to do a million years ago—but that’s close enough.

* * *

Anton Ego’s monologue from Ratatouille:

Julia Dollison sings “Autumn in New York,” accompanied by Ben Monder on guitar, Matt Clohesy on bass, and Ted Poor on drums:

An ArtsJournal Blog