Mrs. T and I watched Alfred Hitchcock’s North by Northwest last week for the first time in a number of years. As we did so, I remembered that I’d written an essay about the film in 1998 for Civilization, a long-defunct magazine published by the Library of Congress. It’s never been collected or reprinted. I still like it, and thought you might feel the same way.

Mrs. T and I watched Alfred Hitchcock’s North by Northwest last week for the first time in a number of years. As we did so, I remembered that I’d written an essay about the film in 1998 for Civilization, a long-defunct magazine published by the Library of Congress. It’s never been collected or reprinted. I still like it, and thought you might feel the same way.

* * *

In 1952, the British film magazine Sight & Sound asked a group of noted critics and directors to pick the ten greatest films of all time. The exercise has since been repeated at decade-long intervals, and to compare the five lists published to date is to receive a priceless lesson in the evolution of taste. Some films appear regularly (Jean Renoir’s The Rules of the Game and Sergei Eisenstein’s Battleship Potemkin made all five lists), others only fleetingly (Luchino Visconti’s La Terra Trema appeared in ninth place in 1962, never to be seen again). About certain films, the consensus is clear: Citizen Kane, which failed to make the first list, shot to the top in 1962 and has been there ever since. Yet the ebb and flow of fashion are no less evident: Ingmar Bergman showed up in 1962 and 1972, Alfred Hitchcock in 1982 and 1992.

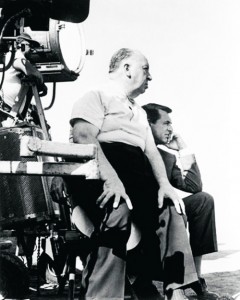

Hitchcock’s belated entry into the pantheon—three years after his death and 20 years after his last important film, The Birds—is among the more revealing aspects of the Canon According to Sight & Sound. For years, the maker of Psycho was generally regarded as a purveyor of cynical shockers unworthy of serious critical consideration. His colleagues, of course, knew him to be a consummate craftsman, but even they seem to have distrusted his artistry. How could a director whose movies were so blatantly lacking in what the U.S. Supreme Court used to call “redeeming social value” possibly belong in the same boat as Bergman or Renoir? And how could anyone take seriously the rotund jokester who exhaled “Goooodeeeeeve-ning” each week on TV, poking fun at himself (and his sponsors) to the mock-macabre accompaniment of Gounod’s Funeral March of a Marionette?

Today, Hitchcock is accepted as a great filmmaker, but the terms of his acceptance are narrowly framed: Vertigo is the only Hitchcock film ever to have made Sight & Sound’s top-ten list. Granted, Vertigo is a marvel, and surely one of his personal best—but why not North by Northwest, regarded by most Hitchcock buffs as a work of comparable stature? The two films, after all, sum up the two sides of his creative personality: James Stewart, the desperate lover of Vertigo, is perfectly balanced by Cary Grant, the supremely self-confident gent in a jam around whom the plot of North by Northwest swirls madly. Both films are technically dazzling; both have masterly scripts; both were scored by Bernard Herrmann, the film composer’s film composer. So what makes Vertigo the classic and North by Northwest the commercial?

Today, Hitchcock is accepted as a great filmmaker, but the terms of his acceptance are narrowly framed: Vertigo is the only Hitchcock film ever to have made Sight & Sound’s top-ten list. Granted, Vertigo is a marvel, and surely one of his personal best—but why not North by Northwest, regarded by most Hitchcock buffs as a work of comparable stature? The two films, after all, sum up the two sides of his creative personality: James Stewart, the desperate lover of Vertigo, is perfectly balanced by Cary Grant, the supremely self-confident gent in a jam around whom the plot of North by Northwest swirls madly. Both films are technically dazzling; both have masterly scripts; both were scored by Bernard Herrmann, the film composer’s film composer. So what makes Vertigo the classic and North by Northwest the commercial?

The answer is, alas, all too simple: North by Northwest is funny, and most critics don’t like funny movies. Or, rather, they don’t trust funny movies. Take another look at those Sight & Sound lists and you’ll notice that except for Buster Keaton’s The General and Charlie Chaplin’s City Lights, The Gold Rush, and Modern Times, all sanctified by their great age, the only Hollywood comedy ever to have been anointed is Singin’ in the Rain, which got the nod in 1982 but predictably failed to make the cut the next time around.

I sometimes wonder whether the reluctance of film professionals to acknowledge the artistic seriousness of comedy has something to do with the fact that their medium, popular though it is, has yet to be fully accepted as co-equal with what highbrows still persist in referring to as the “legitimate” theater. (Obviously, they haven’t been to Broadway lately.) As has lately been pointed out by Roger Ebert, there is no Pulitzer Prize for film, and the Nobel Prize for literature, though it has gone to playwrights often enough, has yet to be awarded to a full-time filmmaker. Could it be that the men and women who make the movies suffer from a collective inferiority complex? Could that be why they insist on awarding Best Picture Oscars to such bloated truckloads of pompous rubbish as Gandhi and Dances With Wolves?

If so, it would also explain why Alfred Hitchcock never received an Oscar for best direction—he simply wasn’t po-faced enough—and I suspect it also has much to do with the fact that North by Northwest, his finest and most characteristic movie, has yet to be widely recognized as such. Even those Hitchcock scholars who know how good it is feel obliged to swaddle their praise in a thick blanket of symbol-snuffling. Hence Donald Spoto, writing in The Art of Alfred Hitchcock, reassures us that North by Northwest “leavens the gravest concerns with a spiky and mature wit….Never has the entire hierarchy of unprincipled political expediency been so ruthlessly dissected.”

The only truly illuminating thing I’ve ever read about North by Northwest is a 1970 essay by the late Charles Thomas Samuels, who spoke admiringly of its “contentless virtuosity.” That’s exactly right, and it is for this reason that North by Northwest, which turns forty this year, has stayed as fresh as this morning’s paint. Here’s how Ernest Lehman, who wrote the script, pitched it to Hitchcock: “One day I said, ‘I want to do a Hitchcock picture to end all Hitchcock pictures, that’s the only kind of picture I want to do, Hitch.’ And by that I meant a movie-movie—with glamour, wit, excitement, movement, big scenes, a large canvas, innocent bystander caught up in great derring-do, in the Hitchcock manner.” To which the great man wistfully replied, “I’ve always wanted to do a chase sequence across the faces of Mount Rushmore.” And off they went, unencumbered by the faintest whiff of social consciousness, in search of thrills—and, just as important, laughs.

The only truly illuminating thing I’ve ever read about North by Northwest is a 1970 essay by the late Charles Thomas Samuels, who spoke admiringly of its “contentless virtuosity.” That’s exactly right, and it is for this reason that North by Northwest, which turns forty this year, has stayed as fresh as this morning’s paint. Here’s how Ernest Lehman, who wrote the script, pitched it to Hitchcock: “One day I said, ‘I want to do a Hitchcock picture to end all Hitchcock pictures, that’s the only kind of picture I want to do, Hitch.’ And by that I meant a movie-movie—with glamour, wit, excitement, movement, big scenes, a large canvas, innocent bystander caught up in great derring-do, in the Hitchcock manner.” To which the great man wistfully replied, “I’ve always wanted to do a chase sequence across the faces of Mount Rushmore.” And off they went, unencumbered by the faintest whiff of social consciousness, in search of thrills—and, just as important, laughs.

Nothing about North by Northwest is so memorable as its high-spirited humor, which is rooted in the casting of Cary Grant as Roger O. Thornhill, the suave advertising executive who ends up hanging by his eyelashes from George Washington’s nose. James Stewart had wanted to play the part, but Hitchcock knew he wasn’t right for it, and stalled until Stewart had to report for work on Bell, Book and Candle, making it possible to hire Grant without hurt feelings on either side. Seen in retrospect, it was the only possible choice, for Grant’s urbane presence is what gives the movie its special tone: even when he’s dodging a crop duster piloted by gun-toting Commie spies, you know he’s going to come out smelling like a dry-cleaned Brooks Brothers suit.

That, needless to say, is the whole point of North by Northwest. Though it pretends to be about the Cold War, it’s really about excitement, pure and simple: it has no more “content” than a roller-coaster ride. This is what Hitchcock had in mind when, midway through location shooting in New York, he said to Ernest Lehman, “Ernie, do you realize what we’re doing in this picture? The audience is like a great organ that you and I are playing. At one moment we play this note on them and get this reaction, and then we play that chord and they react that way. And someday we won’t even have to make a movie—there’ll be electrodes implanted in their brains, and we’ll just press different buttons and they’ll go ‘ooooh’ and ‘aaaah’ and we’ll frighten them, and make them laugh. Won’t that be wonderful?”

The only thing wrong with Hitchcock’s dream is that it came true, more or less. I have a sneaking suspicion that North by Northwest was the inspiration, acknowledged or not, for the decerebrate big-budget thrillers that blight the movie screens of America each summer. From Die Hard to Speed to ConAir, they’re all North by Northwest, only dumbed down, larded with four-letter words, and ruthlessly stripped of charm and wit. This is how far we’ve come since 1958: we started out with Cary Grant and ended up with Keanu Reeves. Yet it can hardly be denied that the first led to the second, for mindless thrills, be they cheap or costly, are still mindless thrills.

It is for this reason that any fully considered avowal of Hitchcock’s cinematic greatness must be followed by an asterisk. The trouble with Hitch isn’t that he is a comedian, but that his comedy is less black than blank. He avoids the jungle of politics by fleeing into the desert of nihilism, and while we gladly follow him there, there is no nourishment in his cold laughter, and never any tears. True comedy is different: I’ve never watched The Rules of the Game, or listened to Mozart’s Marriage of Figaro, without weeping unabashedly at the harsh truths about human nature that can only be spoken with an unsentimental smile.

Still, there are many types of greatness, and Alfred Hitchcock’s kind, idiosyncratic though it is, makes the cut with room to spare. His best films are as watchable today as they were a half-century ago, and speak as directly to the case-hardened children of Generation X as they do to graying baby boomers like me. I recently invited a 23-year-old movie buff, raised on fast-moving indie flicks, to watch North by Northwest with me; she’d never seen it, and I wondered if Hitchcock’s carefully calculated pacing would strike her as arthritic. Not a chance. She watched in rapt silence as Cary Grant slithered drunkenly along the edge of a Long Island cliff, made out with Eva Marie Saint on the 20th-Century Limited (with kissing like that, who needs nude scenes?), and choked on clouds of DDT in a deserted prairie cornfield. “Cool!” she said at the end. “That is one totally cool movie.” And so it is, and ever shall be.

Still, there are many types of greatness, and Alfred Hitchcock’s kind, idiosyncratic though it is, makes the cut with room to spare. His best films are as watchable today as they were a half-century ago, and speak as directly to the case-hardened children of Generation X as they do to graying baby boomers like me. I recently invited a 23-year-old movie buff, raised on fast-moving indie flicks, to watch North by Northwest with me; she’d never seen it, and I wondered if Hitchcock’s carefully calculated pacing would strike her as arthritic. Not a chance. She watched in rapt silence as Cary Grant slithered drunkenly along the edge of a Long Island cliff, made out with Eva Marie Saint on the 20th-Century Limited (with kissing like that, who needs nude scenes?), and choked on clouds of DDT in a deserted prairie cornfield. “Cool!” she said at the end. “That is one totally cool movie.” And so it is, and ever shall be.

* * *

A Guided Tour With Alfred Hitchcock, a promotional short for North by Northwest:

My essay in the May issue of Commentary is occasioned by the publication of Ted Gioia’s

My essay in the May issue of Commentary is occasioned by the publication of Ted Gioia’s