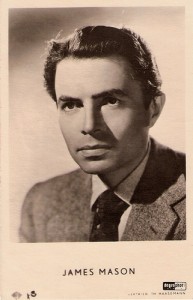

Rare are the dreams of childhood that come true at last, but one of mine, much to my surprise and delight, has actually realized itself, more or less, now that I’m on the brink of late middle age: I have a passably attractive speaking voice. No, it isn’t the dark-brown, gorgeously fine-grained James Mason-type voice for which I always longed in vain, nor do I have the floor-shaking chest resonance that I envy whenever I hear it. But as I listened to myself on the soundtrack of HBO’s Sinatra: All or Nothing at All the other night, I was reminded that I really do sound good when speaking into a microphone. Time has transposed me down a major third, and what was once a light baritone is now a smooth, slightly heavier bass-baritone, one that by all accounts is pleasing to the ear, especially when it’s electronically amplified.

Rare are the dreams of childhood that come true at last, but one of mine, much to my surprise and delight, has actually realized itself, more or less, now that I’m on the brink of late middle age: I have a passably attractive speaking voice. No, it isn’t the dark-brown, gorgeously fine-grained James Mason-type voice for which I always longed in vain, nor do I have the floor-shaking chest resonance that I envy whenever I hear it. But as I listened to myself on the soundtrack of HBO’s Sinatra: All or Nothing at All the other night, I was reminded that I really do sound good when speaking into a microphone. Time has transposed me down a major third, and what was once a light baritone is now a smooth, slightly heavier bass-baritone, one that by all accounts is pleasing to the ear, especially when it’s electronically amplified.

This midlife transformation reminds me of the one experienced by the fictional narrator of Hugh MacLennan’s The Watch That Ends the Night, who to his utter amazement became famous throughout Canada as a radio news commentator:

I’m not a man with much self-confidence and when I was young took it for granted that nobody respected me or paid me any attention. When I was young I was just another of those people who are around, for I had, and still have, a clumsy body of which I was never proud and when I was young I was timid. But living with Catherine had matured me a little and my work on the radio had taught me how to control my voice. I realized now—for I have learned to listen to my own voice as though it came from somebody else, I have learned what it sounds like from listening to play-backs in the studio—I realized now that it was resonant and steady.

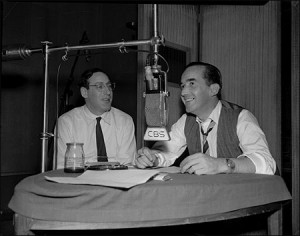

Had I been born three-quarters of a century earlier, I, too, might have done well in radio. But I missed that boat long, long ago, and even if I’d tried to board it, the gelded voices that are favored on what is left of network radio are infinitely different from the ones that dominated the medium in the forgotten days of Ed Murrow and Eric Sevareid. We now prefer snarky pseudo-irony to calm authority. So instead of earning a living by talking into a microphone, I do it by sitting on the aisle and writing about what I see there, and save on rare occasions, the only people who hear my voice are the ones sitting next to me.

Had I been born three-quarters of a century earlier, I, too, might have done well in radio. But I missed that boat long, long ago, and even if I’d tried to board it, the gelded voices that are favored on what is left of network radio are infinitely different from the ones that dominated the medium in the forgotten days of Ed Murrow and Eric Sevareid. We now prefer snarky pseudo-irony to calm authority. So instead of earning a living by talking into a microphone, I do it by sitting on the aisle and writing about what I see there, and save on rare occasions, the only people who hear my voice are the ones sitting next to me.

I hope you don’t think I’m dissatisfied with my lot. Far from it! I am, however, perpetually puzzled by the yawning gap between what I am and what I expected to become. Here’s something I wrote a decade ago:

I was talking the other evening to a fellow critic seated behind me on the aisle of a Broadway theater. He’s eighty, and doesn’t look it, nor does he feel it. “I don’t feel a day over sixty-five,” he told me. “I keep waiting for all that wisdom that’s supposed to come with old age—but it hasn’t come yet.”

As for me, all I know is that nothing I imagined for myself when young has come to pass: everything is different, utterly so. I’m not a schoolteacher, not a jazz musician, not the chief music critic of a major metropolitan newspaper, not a syndicated columnist, not settled and secure. Nor am I the person I expected to be, calm and detached and philosophical: I still cry without warning, laugh too loud, lose my head and heart too easily, the same way I did a quarter-century ago. The person I was is the person I am, only older. Might that be wisdom of a sort?

Ten years later, my fellow critic is a reasonably spritely ninety years old, while I’m closing in fast on sixty. Like him, I wait in vain for wisdom and content. But I can claim for myself a deeply satisfying marriage and a life that continues to be full of happily unexpected developments, not the least of which is the pleasant fact that at long last, I have the voice I always wanted. It may not sound like James Mason, or even Claude Rains, but it’ll do.

* * *

James Mason and Jane Fonda appear as the celebrity contestants on a 1962 episode of Password, hosted by Allen Ludden:

Edward R. Murrow introduces the first episode of This I Believe, a CBS radio series that aired from 1951 to 1955:

(To read Walker Percy’s description of This I Believe in The Moviegoer, go here.)