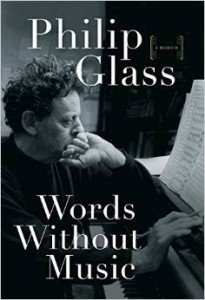

My monthly essay for Commentary, this one for the April issue, is now available on line. It’s occasioned by the publication of Words Without Music, Philip Glass’ autobiography:

My monthly essay for Commentary, this one for the April issue, is now available on line. It’s occasioned by the publication of Words Without Music, Philip Glass’ autobiography:

For all its manifold beauties, the classical music of the 20th century has yet to become popular in America. One sign of its failure to make a deeper mark on our culture is that except for Aaron Copland, the only American classical composer whose name is reasonably well known outside musical circles is Philip Glass. His deliberately repetitive compositional style is familiar enough to have been parodied on The Simpsons and South Park. In this sense, the doyen of musical minimalism is to classical music what Jackson Pollock and Andy Warhol are to the visual arts: He is the one American composer about whom it is possible to make a joke in the expectation that educated people who are not musicians will get it.

Yet despite his own cultural ubiquity, Glass’s pieces are not all that widely performed in this country. While his stage works have been produced by the Metropolitan Opera and other major houses, his instrumental music has yet to be taken up other than sporadically by any world-class soloist, conductor, or ensemble. It is no secret that virtuoso performers loathe his music, which they regard as monotonous and devoid of interpretative challenges. As a result, it is mostly known from the performances and recordings of modern-music specialists and his own Philip Glass Ensemble, as well as from its use in such films as The Thin Blue Line and The Truman Show.

But whatever the long-term prospects for Glass’s music may be, no one now doubts its historic significance. One reason musical modernism finally collapsed under its own weight in the 1970s was that Glass and his like-minded contemporaries refused to kowtow to the anti-tonal regime of the postwar avant-garde musical monopoly. As a result, there is no longer a “mainstream” classical-music style. Instead, all compositional styles—including the minimalism of Glass, John Adams, and Steve Reich—are deemed equally acceptable.

At 78, Glass has come of late to be seen as something of an elder statesman of American music. It stands to reason that so august and consequential a figure should finally have gotten around to writing his memoirs. What is more, Words Without Music: A Memoir is an engaging, even charming book, one of the most readable autobiographies ever written by a classical composer. And no matter what you think of its author’s music, the story that he tells therein will be of much interest to anyone who wants to know how the dogmatic modernism of the ’50s and ’60s gave way to the antinomian postmodernism of the ’70s and after—though whether or not the book converts any of its skeptical readers to the Gospel According to Philip Glass is another matter entirely….

Read the whole thing here.