“Once somebody’s aware of a plot, it’s like a bone sticking out. If it breaks through the skin, it’s very ugly.”

“Once somebody’s aware of a plot, it’s like a bone sticking out. If it breaks through the skin, it’s very ugly.”

Louis Auchincloss, Paris Review interview (Fall 1994)

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City

“Lots of writers have to have whole days or nights to get ready to write; they like to be by a fire, with absolute quiet, with their slippers on and a pipe or something, and then they’re ready to go. They can’t believe you can use five minutes here, ten minutes there, fifteen minutes at another time. Yet it’s only a question of training to learn that trick. If they had to do it that way, they’d be able to—the real writers, that is. I can pick up in the middle of a sentence and then go on. I wrote at night; sometimes I wrote at the office and then practiced law at home. My wife and I never went away on weekends. I wouldn’t recommend that anyone else try this method, but it worked for me.”

“Lots of writers have to have whole days or nights to get ready to write; they like to be by a fire, with absolute quiet, with their slippers on and a pipe or something, and then they’re ready to go. They can’t believe you can use five minutes here, ten minutes there, fifteen minutes at another time. Yet it’s only a question of training to learn that trick. If they had to do it that way, they’d be able to—the real writers, that is. I can pick up in the middle of a sentence and then go on. I wrote at night; sometimes I wrote at the office and then practiced law at home. My wife and I never went away on weekends. I wouldn’t recommend that anyone else try this method, but it worked for me.”

Louis Auchincloss, Paris Review interview (Fall 1994)

One advantage of middle age (yes, it has them) is that you’re still young enough to embrace new technologies, but old enough not to take them for granted. That’s how I feel about my iPod Classic, a replacement for the original iPod that I bought in 2004, three years after the device went on the market. Of all the shiny new gadgets that have entered my life during the past quarter-century, it is the one that has given me the most pleasure.

When I went off to college forty-one years ago, I carted along my record collection, crammed into a four-foot-long metal traveling case that my father built for me in his basement workshop. My iPod now contains many times more music than did that cumbersome box, all of it packed neatly onto a hard drive small enough to slip into my shirt pocket. At present it holds 5,372 “songs” ranging in length from Ned Rorem’s “O You Whom I Often and Silently Come” (twenty-seven seconds) to Willem Mengelberg’s 1928 recording of Tchaikovsky’s Fifth Symphony with the Concertgebouw Orchestra (forty-four minutes). In between can be found examples of every possible kind of music: Bach and the Bad Plus, Fred Astaire and T-Bone Walker, Hank Williams and the Dixieaires, Steely Dan and Lana Del Rey.

When I went off to college forty-one years ago, I carted along my record collection, crammed into a four-foot-long metal traveling case that my father built for me in his basement workshop. My iPod now contains many times more music than did that cumbersome box, all of it packed neatly onto a hard drive small enough to slip into my shirt pocket. At present it holds 5,372 “songs” ranging in length from Ned Rorem’s “O You Whom I Often and Silently Come” (twenty-seven seconds) to Willem Mengelberg’s 1928 recording of Tchaikovsky’s Fifth Symphony with the Concertgebouw Orchestra (forty-four minutes). In between can be found examples of every possible kind of music: Bach and the Bad Plus, Fred Astaire and T-Bone Walker, Hank Williams and the Dixieaires, Steely Dan and Lana Del Rey.

Thanks to my iPod, I carry the whole history of music with me wherever I go, and can listen to any part of it whenever I choose. If I wish, I can push a button and hear Sergei Rachmaninoff playing his Paganini Rhapsody, or listen to a 1908 performance of “Unto Brigg Fair” by Joseph Taylor, the English folksinger from whom Percy Grainger collected that song three years earlier. Having launched my writing career on a manual typewriter, I continue to find no difficulty whatsover in marveling at the mere existence of the ingenious little device that allows me to do so.

The ubiquity of recorded music has been much lamented by any number of wise men. I understand and appreciate their reservations, which Benjamin Britten summed up eloquently in 1964:

One must face the fact today that the vast majority of musical performances take place as far away from the original as it is possible to imagine: I do not mean simply Falstaff being given in Tokyo, or the Mozart Requiem in Madras. I mean of course that such works can be audible in any corner of the globe, at any moment of the day or night, through a loudspeaker, without question of suitability or comprehensibility. Anyone, anywhere, at any time, can listen to the B minor Mass upon one condition only—that they possess a machine. No qualification is required of any sort—faith, virtue, education, experience, age. Music is now free for all. If I say the loudspeaker is the principal enemy of music, I don’t mean that I am not grateful to it as a means of education or study, or as an evoker of memories. But it is not part of true musical experience. Regarded as such it is simply a substitute, and dangerous because deluding. Music demands more from a listener than simply the possessions of a tape-machine or a transistor radio. It demands some preparation, some effort, a journey to a special place, saving up for a ticket, some homework on the program perhaps, some clarification of the ears and sharpening of the instincts. It demands as much effort on the listener’s part as the other two corners of the triangle, this holy triangle of composer, performer and listener.

In truth, I think Britten was mostly right. Among other unfortunate things, the ubiquity of recorded music has largely killed off the amateur back-porch music-making that was one of the joys of my youth. But that was well on the way to happening long before the invention of the laptop computer and its offshoots. And if we are more passive listeners today, then we also have access to an infinitely wider and more varied range of listening possibilities than we did when I was young.

In any case, it doesn’t really matter whether he was right: the deed is done, and only a self-consciously curmudgeonly fool would bemoan the results. To borrow a line from V.S. Naipaul, the world is what it is. Far better, then, to seize what it offers and make the most of it—and that, for me, includes the iPod. Two days ago I downloaded a recording of Dmitri Shostakovich’s Piano Quintet that was made by Shostakovich and the Beethoven Quartet in Moscow in 1940, one month after they gave the premiere of that masterpiece. Do I regret being able to do so? Not in the slightest—any more than I regret being able to go to YouTube and watch videos of Britten performing his own music.

It was with much bemusement that I learned last year that Apple had finally stopped manufacturing the iPod Classic. It is now officially obsolete, superseded by iPads and smartphones and various other shiny do-it-all gadgets, none of which I own. I continue instead to rely on my trusty iPod, my increasingly dilapidated MacBook, and my positively ancient flip phone, and for the present I see no compelling reason to replace any of them. Sooner or later, of course, I’ll discard them all and lurch into a new technological age, though not quite yet, life being complicated enough as is. But when I do, I hope that I continue to feel some sliver of the shivery thrill that I felt the first time I downloaded a song from iTunes. One should never get used to miracles.

It was with much bemusement that I learned last year that Apple had finally stopped manufacturing the iPod Classic. It is now officially obsolete, superseded by iPads and smartphones and various other shiny do-it-all gadgets, none of which I own. I continue instead to rely on my trusty iPod, my increasingly dilapidated MacBook, and my positively ancient flip phone, and for the present I see no compelling reason to replace any of them. Sooner or later, of course, I’ll discard them all and lurch into a new technological age, though not quite yet, life being complicated enough as is. But when I do, I hope that I continue to feel some sliver of the shivery thrill that I felt the first time I downloaded a song from iTunes. One should never get used to miracles.

* * *

Here is the Peanuts strip from which the above panel was adapted for commercial use. It was originally published in 1952.

Peter Pears and Benjamin Britten perform Britten’s arrangement of “O Waly Waly.” This performance was taped in front of an audience at the BBC’s Riverside Studios in 1964:

In 2004 I had my first glimpse of Sondheim’s work at a Chicago Shakespeare Theater production of A Little Night Music that swept me off my feet and left me in tears (this, I find, is happening a lot more often the older I get, and bears no necessary relation to the quality of the movie/book/play/sporting event). A few months later, in New York, Terry took me to see an all-stops-pulled-out production of Sweeney Todd at City Opera, and several months after that we saw a tiny, black-box-theater version of Todd back here in Chicago. I guess I got lucky–every one of these stagings was played with talent and conviction, and after spending half a life unaware of the force that is Sondheim, I was half in love….

Read the whole thing here.

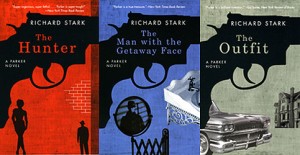

I am, as regular readers of this blog need no reminding, an ardent admirer of the novels of “Richard Stark,” the pseudonym that the late Donald E. Westlake used when writing about Parker, a career criminal of all-too-believable heartlessness. I had the privilege a few years ago of writing an introduction to the University of Chicago’s uniform-edition reprints of Flashfire and Firebreak, two of the very best Parker novels, and I speculated therein on their popularity, which is in certain ways a puzzlement:

I am, as regular readers of this blog need no reminding, an ardent admirer of the novels of “Richard Stark,” the pseudonym that the late Donald E. Westlake used when writing about Parker, a career criminal of all-too-believable heartlessness. I had the privilege a few years ago of writing an introduction to the University of Chicago’s uniform-edition reprints of Flashfire and Firebreak, two of the very best Parker novels, and I speculated therein on their popularity, which is in certain ways a puzzlement:

Anyone who doubts the existence of original sin would do well to reflect on the popularity of these unsettling books, whose “hero,” lest we forget, is a hard-eyed monster of self-will, the kind of guy you don’t want to meet anywhere near a dark alley. Parker’s only virtues are his intelligence and his professionalism—but somehow you always end up rooting for him. Nietzsche knew why: when you look into an abyss, the abyss looks into you. When I first started reading about Parker, I thought of the words of Dostoevsky’s Ivan Karamazov: “If you were to destroy in humanity the belief in its immortality, not only love but every vital force for the continuation of earthly life would at once dry up. Moreover, then nothing would be immoral any more, everything would be permitted, even cannibalism.” Up to a point, that applies to Parker, a man to whom nothing but amateurishness is immoral. Even more to the point, though, is Liliana Cavani’s 2002 film version of Ripley’s Game, in which these words are put into the mouth of Tom Ripley, Patricia Highsmith’s anti-hero: “I lack your conscience and when I was young that troubled me. It no longer does. I don’t worry about being caught because I don’t believe anyone is watching.”

Like Ripley, who is a real sociopath, Parker has no conscience. Somehow, though, I doubt that has ever troubled him. I think he got up one morning, decided for reasons known only to himself that no one was watching except for the cops, and decided to act accordingly. Nor do I think there was anything dramatic about his decision, no Farewell remorse…evil be thou my good moment to stun the groundlings. And that’s what makes Parker so interesting, so seductive, and so wholly unlike most of the rest of us: he just doesn’t care, and never did.

All this is true as far as it goes, but I’m not sure that it goes far enough. Parker is, after all, a brute by any conceivable standard of conduct, in addition to which he is portrayed by Stark as a creature so cold as to be, at least in theory, utterly unsympathetic. Why, then, do we—do I—wish him well? For we do: about that there can be no doubt. We want him to prevail in his capers, no matter the cost in human life. I know, they’re only novels, but so what? Real or not, Parker is a bad man. What, then, makes him so attractive?

Part of the answer may have to do with the fact that I am not infrequently drawn to the Parker novels at times when my own life is more chaotic than usual. While I’m not obsessive about much of anything, I do prize order—I’m a native-born list-maker—and I don’t much care to be reminded that I actually have very little control over the world and my place in it. Neither does Parker, but unlike the rest of us, he’s prepared to do something about it, up to and including murder. Surely that is the ultimate source of his appeal: he does as he pleases, and gets away with it. Moreover, he does it in the name of order—his order. The world exists to satisfy his wants, which he pursues in a manner so disciplined that it is all but impossible not to admire, however backhandedly.

Part of the answer may have to do with the fact that I am not infrequently drawn to the Parker novels at times when my own life is more chaotic than usual. While I’m not obsessive about much of anything, I do prize order—I’m a native-born list-maker—and I don’t much care to be reminded that I actually have very little control over the world and my place in it. Neither does Parker, but unlike the rest of us, he’s prepared to do something about it, up to and including murder. Surely that is the ultimate source of his appeal: he does as he pleases, and gets away with it. Moreover, he does it in the name of order—his order. The world exists to satisfy his wants, which he pursues in a manner so disciplined that it is all but impossible not to admire, however backhandedly.

Backflash, another of the Parker novels that I like best, contains this illuminating paragraph:

So the question is, why not gamble? Parker’d never thought about it, he just knew it was pointless and uninteresting. He said, “Turn myself over to random events? Why? The point is to control events, and they’ll still get away from you anyway. Why make things worse? Jump out a window, see if a mattress truck goes by. Why? Only if the room’s on fire.”

I don’t gamble, either, and when I first read that passage, I smiled at the sound of a kindred spirit. Nor did I cross myself hastily and whisper, No, no, just kidding, I’m not that kind of guy! To be sure, I’m not that kind of guy, or anything remotely like him, but I know very well that there is a part of me, however small, that is tempted to adopt Parker’s absolutism as a mode of life. Indeed, there can’t be many of us who don’t feel that temptation on a fairly regular basis, never more than when the dam that is our daily life suddenly starts springing multiple leaks. When things go wrong for Parker, by contrast, he knows exactly what to do: he shoots people until they go right again. He likes things neat.

Such neatness, needless to say, is an idle fantasy. Sooner or later everybody’s dam starts springing leaks, and in time it breaks wide open and washes us away. But it’s peculiarly soothing to imagine the existence of a man who adamantly refuses to turn himself over to random events, whatever they may be, and it goes down even more smoothly when you find yourself in the waiting room of an intensive-care unit, or midway through a sleepless night. Maybe that’s what fantasy is all about.

Satchmo at the Waldorf, my first play, has already been performed off Broadway and in Lenox, New Haven, Orlando, and Philadelphia. As of now, it’s set to be produced in five more American cities between now and the summer of 2016. Here’s an update on where and when you can see it:

Satchmo at the Waldorf, my first play, has already been performed off Broadway and in Lenox, New Haven, Orlando, and Philadelphia. As of now, it’s set to be produced in five more American cities between now and the summer of 2016. Here’s an update on where and when you can see it:

• MAY 26-JUNE 7, 2015 The original off-Broadway production of Satchmo, starring John Douglas Thompson and directed by Gordon Edelstein, is transferring to the Wallis Annenberg Center for the Performing Arts in Beverly Hills, California. To order tickets or for more information, go here.

• JANUARY-FEBRUARY 2016 The original production will then be remounted by San Francisco’s American Conservatory Theater. For more information, go here.

• JANUARY 7-FEBRUARY 7, 2016 Chicago’s Court Theatre presents its own production of Satchmo, directed by Charles Newell. The star has not yet been announced. For more information, go here.

• FEBRUARY 18-MARCH 6, 2016 After the original production of Satchmo closes in San Francisco, it will transfer directly to Theaterworks, located on the campus of the University of Colorado, Colorado Springs. For more information, go here.

• MAY 11-JUNE 12, 2016 Florida’s Palm Beach Dramaworks presents its own production of Satchmo. The star and director have not yet been announced. For more information, go here.

Additional productions are in the works. I’ll keep you posted.

An ArtsJournal Blog