“Mortal danger is an effective antidote for fixed ideas.”

“Mortal danger is an effective antidote for fixed ideas.”

Erwin Rommel, The Rommel Papers

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City

Here’s my list of recommended Broadway, off-Broadway, and out-of-town shows, updated weekly. In all cases, I gave these shows favorable reviews (if sometimes qualifiedly so) in The Wall Street Journal when they opened. For more information, click on the title.

BROADWAY:

• A Gentleman’s Guide to Love & Murder (musical, PG-13, nearly all performances sold out, reviewed here)

• It’s Only a Play (comedy, PG-13/R, closes June 7, reviewed here)

• Matilda (musical, G, all performances sold out, reviewed here)

• Les Misérables (musical, G, most performances sold out, too long and complicated for young children, reviewed here)

• On the Town (musical, G, contains double entendres that will not be intelligible to children, reviewed here)

• On the Twentieth Century (musical, G/PG-13, all performances sold out, closes July 5, contains very mild sexual content, reviewed here)

• On the Twentieth Century (musical, G/PG-13, all performances sold out, closes July 5, contains very mild sexual content, reviewed here)

OFF BROADWAY:

• The Fantasticks (musical, G, suitable for children capable of enjoying a love story, closes May 3, reviewed here)

• Hamilton (historical musical, PG-13, closes May 3, moves to Broadway Aug. 6, reviewed here)

CLOSING SOON IN SARASOTA, FLA.:

• Both Your Houses (political satire, G/PG-13, closes Apr. 12, reviewed here)

• The Matchmaker (romantic farce, G, closes Apr. 11, reviewed here)

CLOSING FRIDAY OFF BROADWAY:

• Lives of the Saints (six one-act comedies, PG-13/R, reviewed here)

CLOSING SUNDAY ON BROADWAY:

• Cabaret (musical, PG-13/R, some performances sold out last week, reviewed here)

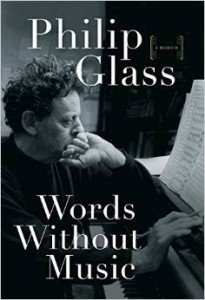

My monthly essay for Commentary, this one for the April issue, is now available on line. It’s occasioned by the publication of Words Without Music, Philip Glass’ autobiography:

My monthly essay for Commentary, this one for the April issue, is now available on line. It’s occasioned by the publication of Words Without Music, Philip Glass’ autobiography:

For all its manifold beauties, the classical music of the 20th century has yet to become popular in America. One sign of its failure to make a deeper mark on our culture is that except for Aaron Copland, the only American classical composer whose name is reasonably well known outside musical circles is Philip Glass. His deliberately repetitive compositional style is familiar enough to have been parodied on The Simpsons and South Park. In this sense, the doyen of musical minimalism is to classical music what Jackson Pollock and Andy Warhol are to the visual arts: He is the one American composer about whom it is possible to make a joke in the expectation that educated people who are not musicians will get it.

Yet despite his own cultural ubiquity, Glass’s pieces are not all that widely performed in this country. While his stage works have been produced by the Metropolitan Opera and other major houses, his instrumental music has yet to be taken up other than sporadically by any world-class soloist, conductor, or ensemble. It is no secret that virtuoso performers loathe his music, which they regard as monotonous and devoid of interpretative challenges. As a result, it is mostly known from the performances and recordings of modern-music specialists and his own Philip Glass Ensemble, as well as from its use in such films as The Thin Blue Line and The Truman Show.

But whatever the long-term prospects for Glass’s music may be, no one now doubts its historic significance. One reason musical modernism finally collapsed under its own weight in the 1970s was that Glass and his like-minded contemporaries refused to kowtow to the anti-tonal regime of the postwar avant-garde musical monopoly. As a result, there is no longer a “mainstream” classical-music style. Instead, all compositional styles—including the minimalism of Glass, John Adams, and Steve Reich—are deemed equally acceptable.

At 78, Glass has come of late to be seen as something of an elder statesman of American music. It stands to reason that so august and consequential a figure should finally have gotten around to writing his memoirs. What is more, Words Without Music: A Memoir is an engaging, even charming book, one of the most readable autobiographies ever written by a classical composer. And no matter what you think of its author’s music, the story that he tells therein will be of much interest to anyone who wants to know how the dogmatic modernism of the ’50s and ’60s gave way to the antinomian postmodernism of the ’70s and after—though whether or not the book converts any of its skeptical readers to the Gospel According to Philip Glass is another matter entirely….

Read the whole thing here.

I scarcely ever see movies when they’re new—my day job keeps me too busy—and so I only just caught up last night with Wes Anderson’s Moonrise Kingdom, which I thought as poignant and exquisitely wrought as the music by Benjamin Britten that is used to such miraculously apposite effect on the soundtrack of the film.

I scarcely ever see movies when they’re new—my day job keeps me too busy—and so I only just caught up last night with Wes Anderson’s Moonrise Kingdom, which I thought as poignant and exquisitely wrought as the music by Benjamin Britten that is used to such miraculously apposite effect on the soundtrack of the film.

Since I don’t have the time or energy to expound at length on Moonrise Kingdom, I thought I’d instead reprint the only thing I’ve ever written about Anderson, my 2005 Crisis review of The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou. It is, I think, to the point, albeit a bit obliquely so.

* * *

Wes Anderson’s latest film, like Rushmore and The Royal Tenenbaums before it, is both distractingly quirky and more than a little bit precious, but beneath its clever-clever surface you’ll find real intelligence—and real feeling. It is, in fact, a deeply serious film disguised as a parody, though I can’t see how anyone but a critic could fail to get the point. The most immediate and unlikely object of Anderson’s satire is, of all people, Jacques Cousteau. Steve Zissou (Bill Murray) is a middle-aged oceanographer-filmmaker-celebrity for whom the living is no longer easy. His increasingly dull documentaries have fallen from favor with moviegoers, and Oseary Drakoulias (Michael Gambon), his slightly crooked producer, is unable to raise the money for him to make another. Worse yet, Eleanor (Anjelica Huston), Zissou’s wealthy, blasé wife, is on the verge of leaving him for his hated rival Alistair Hennessey (Jeff Goldblum). His once-settled life, in short, is on the verge of unraveling. Then Ned Plimpton (Owen Wilson), a clean-cut young airline pilot, shows up without warning on his doorstep, claiming to be his long-lost illegitimate son, with Jane Winslett-Richardson (Cate Blanchett), a pregnant British journalist whose mission is to expose Zissou as an over-the-hill hack, arriving on the very next boat….

In addition to this scrambled gumbo of deliberately familiar plot devices, Anderson and co-screenwriter Noah Baumbach (Kicking and Screaming) have upped the satirical ante yet another notch by casting The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou as something closely resembling a Spinal Tap-style “mockumentary,” albeit with a twist: Zissou and the crew of his ship, the Belafonte, are themselves in the process of making a movie about their daily lives. Hence The Life Aquatic is a doubly self-reflexive exercise in postmodernism, a real film about a nonexistent one.

Regular readers of this column don’t need to be reminded that I loathe postmodernism. The difference is that Anderson has here enlisted postmodern irony in the service of underscoring a quintessentially postmodern problem: the way in which postmodern man uses irony to insulate himself from feeling. As we learn in the course of The Life Aquatic, Zissou was once an idealistic young man who loved the sea for its own sake; then he chose to use it as a means to fame and fortune, and his love curdled and grew sour. By trading cynically on his youthful passion, Zissou has lost touch with his inner life. Not only does he now make voyages solely in order to film them, but he lives for the same reason: Everything he does is fodder for his movies. Hence the boredom bordering on paralysis that has him in its grip, which is, as any proper theologian will instantly recognize, a classic symptom of accidie, the deadly sin of spiritual sloth.

It makes perfect sense that Anderson has chosen Bill Murray to play Zissou. Though his acting is narrowly limited in range, Murray is a kind of comic genius when it comes to embodying accidie on screen. Twice before, in Groundhog Day and Lost in Translation, he has played terminally disillusioned characters whose souls are deadened by sloth, and done it brilliantly. He does the same thing—no less brilliantly—in The Life Aquatic, playing a contemporary cynic whose feelings are so thickly encased in a shell of irony that it’s depressing just to look at him. Everyone else in The Life Aquatic is cunningly cast (especially the amazing Cate Blanchett, that best of all possible actress-chameleons), but it’s Murray’s performance that is the film’s moral center. Is he too deeply mired in sloth to be resurrected by the prospect of love? Though we laugh at his deliciously exaggerated ennui, we still want to know the answer—and hope against hope that it’s the right one.

It makes perfect sense that Anderson has chosen Bill Murray to play Zissou. Though his acting is narrowly limited in range, Murray is a kind of comic genius when it comes to embodying accidie on screen. Twice before, in Groundhog Day and Lost in Translation, he has played terminally disillusioned characters whose souls are deadened by sloth, and done it brilliantly. He does the same thing—no less brilliantly—in The Life Aquatic, playing a contemporary cynic whose feelings are so thickly encased in a shell of irony that it’s depressing just to look at him. Everyone else in The Life Aquatic is cunningly cast (especially the amazing Cate Blanchett, that best of all possible actress-chameleons), but it’s Murray’s performance that is the film’s moral center. Is he too deeply mired in sloth to be resurrected by the prospect of love? Though we laugh at his deliciously exaggerated ennui, we still want to know the answer—and hope against hope that it’s the right one.

Part of what makes The Life Aquatic so interesting is that it, too, embodies in a larger way the problem faced by Zissou, whose dark night of the soul is so carefully wrapped in multiple layers of irony and whimsy that you catch yourself wondering whether Anderson might suffer from a touch of the same spiritual disorder as does his character. The virtuosity with which Anderson spoofs so many different varieties of cinematic triteness is marvelous to behold, but it’s also a way of avoiding the need to be unequivocal about the spiritual point he so clearly wishes to make. Yet for all its slippery indirection, The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou still manages to get its point across, not only subtly but with a smile. I’ll take postmodern subtlety over political point-making any day of the week.

* * *

The theatrical trailers for Moonrise Kingdom and The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou:

An old friend of mine used to take every Friday night off without fail. He’d come home from work, retire to his study, eat dinner from a tray, and spend the whole evening listening to his huge, meticulously organized collection of 78s, through which he worked his way in strict alphabetical order every few years. No matter what else was happening in the world, however dire it might be (or seem to be), he shut the shop down one night a week and disappeared from the world. I spent many Friday nights with him in the last two years of his life, and I enjoyed them not only because he was a great listener, but also because spending the evening with him prevented me from spending it in an aisle seat or a noisy nightclub, or at my desk….

Read the whole thing here.

An ArtsJournal Blog