“I would not kill my enemies, but I will make them get down on their knees. I will, I can, I must.”

“I would not kill my enemies, but I will make them get down on their knees. I will, I can, I must.”

Maria Callas (quoted in John Ardoin, Callas: The Art and the Life)

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City

The February issue of Commentary, which is now available on line, contains an essay by me on Bob Hope, occasioned by Richard Zoglin’s recently published biography of the comedian, who died in 2003 at the age of 100 and is now largely forgotten:

The February issue of Commentary, which is now available on line, contains an essay by me on Bob Hope, occasioned by Richard Zoglin’s recently published biography of the comedian, who died in 2003 at the age of 100 and is now largely forgotten:

Reading Hope: Entertainer of the Century, one comes away with the suspicion that Zoglin felt obliged to inflate Hope’s place in American culture in order to persuade a younger generation of book editors to consider publishing a 576-page biography of a forgotten star. And while Hope offers an impressively detailed depiction of Hope’s life and work, it turns out that he was, like so many other entertainers, less interesting as a human being than as a performer. Moreover, nothing that Zoglin tells us about Hope’s private life is in any way revealing. It was an open secret that he was a compulsive philanderer, and none of his lovers seem to have gone on the record about their relationships with him. Beyond that, he was by most accounts a dull, opaque man who came alive only in front of an audience or a camera.

Nevertheless, Hope is of real value as a chronicle of a career. For even though Bob Hope’s work is no longer capable of holding the attention of modern audiences, it is still interesting to learn the details of how he turned himself into a star and then managed to stay on top of the mass-culture heap long after most of his less-driven contemporaries had vanished from sight. But Zoglin, for all his admirable thoroughness, inexplicably fails to emphasize the central fact about Hope and his career—one that not only goes a long way toward explaining why he was so successful, but also why we no longer find him funny.

Simply: He wasn’t Jewish….

Read the whole thing here.

* * *

“Issue No. 48” of Army-Navy Screen Magazine, a biweekly newsreel produced by the U.S. Signal Corps between 1943 and 1946. This 1944 episode is a pictorial version of Command Performance, a World War II radio show that was produced for and distributed to American troops. The master of ceremonies for this broadcast was Bob Hope:

I recently saw a stage actress I know in an episode of a popular TV series. This was a new experience for me. I’ve watched any number of writer friends hold forth on talk shows, and I’ve even tuned into David Letterman to see a band whose members I know quite well. But all those people were being themselves, more or less, whereas my actress friend was pretending to be someone else. Of course she was in one sense wholly herself (I knew her smile in an instant/I knew the curve of her face), and the part she played drew deeply on her familiar energy. Nor was she made up in any deceptive way: she looked like the person I know. Yet some uncanny transformation had nonetheless taken place, and I found myself to be more than a little bit disoriented as I watched her on the screen….

Read the whole thing here.

I haven’t seen Ava DuVernay’s Selma and so have no opinion of it, but I’ve been taking a personal interest in the ongoing debate over its alleged deviations from the historical record, and whether such deviations are a legitimate object of critical concern.

I haven’t seen Ava DuVernay’s Selma and so have no opinion of it, but I’ve been taking a personal interest in the ongoing debate over its alleged deviations from the historical record, and whether such deviations are a legitimate object of critical concern.

Mark Harris, the author of Five Came Back: A Story of Hollywood and the Second World War, has written an extremely fine essay about this debate that deserves to be read widely. Here’s part of it:

In a piece for Politico titled What Selma Gets Wrong, Mark Updegrove, who runs the LBJ Presidential Library, professes to understand the difference between what historians like him and writer-directors like DuVernay do. “The former builds a narrative based on fact,” he explains, “while the latter often bends truth for the sake of a story’s arc or tempo.”

That definition may sound reasonable on the surface, but it proceeds from an enduring fallacy about historical drama shared by almost everyone who complains about it—namely, that the reason drama “bends truth” is that it requires shortcuts to keep things moving swiftly and neatly. There is no acknowledgment—because there is no understanding—that sometimes historical fiction departs from facts in order to reach for abstract, thematic, or complexly intuitive truths that even the most diligently fact-checked histories and biographies can fail to illuminate. A baseline belief that history books and historical fiction are both after truth but use different means to reach it would be a more respectful place to start a discussion of Selma (or any other film that deals with real events). But instead of a conversation, what we have now is a ritual awards-season indictment, one that starts from the self-regarding premise that Hollywood writers and directors are by and large too lazy, stupid, pandering, or corner-cutting to do the nitty-gritty work of historians or journalists, and that they must therefore be caught out and scolded because otherwise the public—which in this line of thinking is also lazy and stupid—will be hoodwinked by them….

While I’m with Harris all the way, I do think a caveat is in order, for it’s also regrettably true that a growing number of ill-read moviegoers know what they “know” about the past from biopics and historical films like Selma, some of which are—to put it mildly—truer to the facts than others.

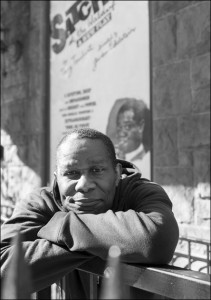

As it happens, I have a horse in this particular race, since my own first play, Satchmo at the Waldorf, is a historical drama. It’s not in any way a literal retelling of the episode in Louis Armstrong’s life that is portrayed therein: I made it all up, though the play is based in large part on things that the characters really said and did. And while I meant for the action to seem plausible, I wasn’t trying to fool anybody into thinking that it really happened. Satchmo at the Waldorf is a work of art, not a work of history—and I have good reason to know the difference. Having first written a primary-source biography of Armstrong, I then wrote a play about him that was extensively informed by fact, but was not itself factual.

As it happens, I have a horse in this particular race, since my own first play, Satchmo at the Waldorf, is a historical drama. It’s not in any way a literal retelling of the episode in Louis Armstrong’s life that is portrayed therein: I made it all up, though the play is based in large part on things that the characters really said and did. And while I meant for the action to seem plausible, I wasn’t trying to fool anybody into thinking that it really happened. Satchmo at the Waldorf is a work of art, not a work of history—and I have good reason to know the difference. Having first written a primary-source biography of Armstrong, I then wrote a play about him that was extensively informed by fact, but was not itself factual.

Is there anything wrong with that? Not in the slightest. But I also took care to reprint in the program of Satchmo at the Waldorf the same disclaimer that will appear in the published script: “This is a work of fiction, freely based on fact.” Time was when such a disclaimer wouldn’t have been necessary, but in our postmodern era of historical ignorance, I incline to think that it’s needed in order to prevent audiences from assuming that the play or movie that they’re watching is covered by what lawyers call an “implicit warranty” of literal truthfulness. The current debate over Selma would have been strangled in its cradle had it been prefaced by a similar statement.

Enough said? I doubt it. But that’s what I think.

I wrote a “Sightings” column last November about Desert Island Discs, the long-running BBC radio series whose guests are invited to choose and talk about the records that they’d take with them were they to be marooned on an imaginary island. In the course of researching my column, I found out that the BBC didn’t possess an archival tape of Louis Armstrong’s 1968 appearance on Desert Island Discs, which was presumed to be lost forever.

I wrote a “Sightings” column last November about Desert Island Discs, the long-running BBC radio series whose guests are invited to choose and talk about the records that they’d take with them were they to be marooned on an imaginary island. In the course of researching my column, I found out that the BBC didn’t possess an archival tape of Louis Armstrong’s 1968 appearance on Desert Island Discs, which was presumed to be lost forever.

According to Desert Island Discs: 70 Years of Castaways, Sean Magee’s 2012 history of the program:

One true legend who had to be omitted from [the book] on purely practical grounds is Louis Armstrong, cast away by Roy Plomley [the original host of Desert Island Discs] in 1968. There is no audio of their interview, and the surviving transcript is simply too patchy to enable any part of it to be reproduced.

This passage caught my eye at once, for I knew that Armstrong’s own reel-to-reel tape of the show survived in the Louis Armstrong Collection. Not only had I listened to the tape in 2006, but I subsequently described the broadcast in some detail and quoted from it in Pops, my 2009 biography of Armstrong.

Here’s what I wrote in Pops:

He picked three of his own sides, “Blueberry Hill,” “Mack the Knife,” and “What a Wonderful World,” plus the version of “Bess, You Is My Woman Now” that he had recorded with Ella Fitzgerald” in 1957 and a trio of 78s by Guy Lombardo, Jack Teagarden, and “my man Bobby Hackett.” Yet he also made room for Barbra Streisand’s “People,” praising her as “Madame Streisand…she’s tryin’ to outsing everybody this year!” At sixty-seven his ears were still wide open.

I sent an e-mail to the Desert Island Discs website telling them that the tape existed, and within a few days they wrote back to ask how they could get a copy. I directed them to Ricky Riccardi, my fellow Armstrong biographer, who works at the Armstrong Archive. Ricky duly sent the BBC a copy of the tape, and on Saturday they uploaded it to the Desert Island Discs website for everyone in the world to hear and enjoy. I am exceedingly proud to have made that possible.

I sent an e-mail to the Desert Island Discs website telling them that the tape existed, and within a few days they wrote back to ask how they could get a copy. I directed them to Ricky Riccardi, my fellow Armstrong biographer, who works at the Armstrong Archive. Ricky duly sent the BBC a copy of the tape, and on Saturday they uploaded it to the Desert Island Discs website for everyone in the world to hear and enjoy. I am exceedingly proud to have made that possible.

To listen to the show, go here.

To read the Guardian’s story about the discovery of the tape, go here. This is, by the way, the only news story I’ve seen to date that credits me with the discovery. (I was more than a little bit surprised that the BBC itself neglected to do so.)

UPDATE: Armstrong scholar Ricky Riccardi blogs in illuminating detail on this broadcast.

When I was young, everybody I knew watched The Andy Griffith Show Today there are no TV shows that “everybody” watches, and no movies that everyone has seen. Indeed, the American film industry is about to devote its annual prime-time infomercial to celebrating five movies that most Americans haven’t seen, don’t plan to see, and couldn’t even if they wanted to (at least not until they come out on DVD).

None of this is good or bad, merely different, but for a person born in 1956–even one who has kept a fairly close eye on postmodern culture–it’s definitely disorienting….

Read the whole thing here.

An ArtsJournal Blog