I haven’t seen Ava DuVernay’s Selma and so have no opinion of it, but I’ve been taking a personal interest in the ongoing debate over its alleged deviations from the historical record, and whether such deviations are a legitimate object of critical concern.

I haven’t seen Ava DuVernay’s Selma and so have no opinion of it, but I’ve been taking a personal interest in the ongoing debate over its alleged deviations from the historical record, and whether such deviations are a legitimate object of critical concern.

Mark Harris, the author of Five Came Back: A Story of Hollywood and the Second World War, has written an extremely fine essay about this debate that deserves to be read widely. Here’s part of it:

In a piece for Politico titled What Selma Gets Wrong, Mark Updegrove, who runs the LBJ Presidential Library, professes to understand the difference between what historians like him and writer-directors like DuVernay do. “The former builds a narrative based on fact,” he explains, “while the latter often bends truth for the sake of a story’s arc or tempo.”

That definition may sound reasonable on the surface, but it proceeds from an enduring fallacy about historical drama shared by almost everyone who complains about it—namely, that the reason drama “bends truth” is that it requires shortcuts to keep things moving swiftly and neatly. There is no acknowledgment—because there is no understanding—that sometimes historical fiction departs from facts in order to reach for abstract, thematic, or complexly intuitive truths that even the most diligently fact-checked histories and biographies can fail to illuminate. A baseline belief that history books and historical fiction are both after truth but use different means to reach it would be a more respectful place to start a discussion of Selma (or any other film that deals with real events). But instead of a conversation, what we have now is a ritual awards-season indictment, one that starts from the self-regarding premise that Hollywood writers and directors are by and large too lazy, stupid, pandering, or corner-cutting to do the nitty-gritty work of historians or journalists, and that they must therefore be caught out and scolded because otherwise the public—which in this line of thinking is also lazy and stupid—will be hoodwinked by them….

While I’m with Harris all the way, I do think a caveat is in order, for it’s also regrettably true that a growing number of ill-read moviegoers know what they “know” about the past from biopics and historical films like Selma, some of which are—to put it mildly—truer to the facts than others.

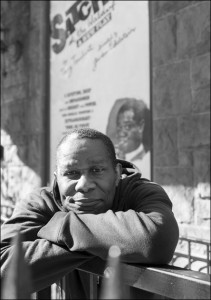

As it happens, I have a horse in this particular race, since my own first play, Satchmo at the Waldorf, is a historical drama. It’s not in any way a literal retelling of the episode in Louis Armstrong’s life that is portrayed therein: I made it all up, though the play is based in large part on things that the characters really said and did. And while I meant for the action to seem plausible, I wasn’t trying to fool anybody into thinking that it really happened. Satchmo at the Waldorf is a work of art, not a work of history—and I have good reason to know the difference. Having first written a primary-source biography of Armstrong, I then wrote a play about him that was extensively informed by fact, but was not itself factual.

As it happens, I have a horse in this particular race, since my own first play, Satchmo at the Waldorf, is a historical drama. It’s not in any way a literal retelling of the episode in Louis Armstrong’s life that is portrayed therein: I made it all up, though the play is based in large part on things that the characters really said and did. And while I meant for the action to seem plausible, I wasn’t trying to fool anybody into thinking that it really happened. Satchmo at the Waldorf is a work of art, not a work of history—and I have good reason to know the difference. Having first written a primary-source biography of Armstrong, I then wrote a play about him that was extensively informed by fact, but was not itself factual.

Is there anything wrong with that? Not in the slightest. But I also took care to reprint in the program of Satchmo at the Waldorf the same disclaimer that will appear in the published script: “This is a work of fiction, freely based on fact.” Time was when such a disclaimer wouldn’t have been necessary, but in our postmodern era of historical ignorance, I incline to think that it’s needed in order to prevent audiences from assuming that the play or movie that they’re watching is covered by what lawyers call an “implicit warranty” of literal truthfulness. The current debate over Selma would have been strangled in its cradle had it been prefaced by a similar statement.

Enough said? I doubt it. But that’s what I think.