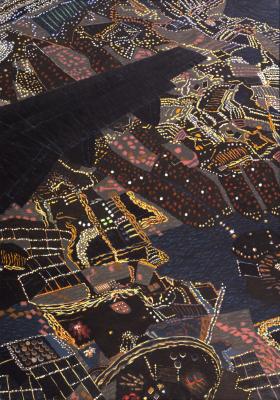

I flew up from Florida to New York City late on Friday afternoon, mere hours after the blood stopped flowing in Paris. I had a brilliantly clear view of lower Manhattan after dark as our plane swung round toward LaGuardia Airport. It was impossible for me not to think of the terrible day fourteen years ago when I flew back to New York from my childhood home in a half-empty plane, stunned by the grotesque carnage that I had seen on my mother’s TV and transfixed by the plume of smoke and ash rising from Ground Zero, which was visible from my window seat.

I flew up from Florida to New York City late on Friday afternoon, mere hours after the blood stopped flowing in Paris. I had a brilliantly clear view of lower Manhattan after dark as our plane swung round toward LaGuardia Airport. It was impossible for me not to think of the terrible day fourteen years ago when I flew back to New York from my childhood home in a half-empty plane, stunned by the grotesque carnage that I had seen on my mother’s TV and transfixed by the plume of smoke and ash rising from Ground Zero, which was visible from my window seat.

My life has changed utterly since then, transformed beyond recognition by a happy marriage, the death of a parent, and the unforeseen advent of an creative urge that has made me over into a part-time artist. But the world in which I live today is in one important respect no different than it was in 2001: now as then, we are besieged by men with twisted souls who march in lockstep to a still small voice that tells them to hate the world as it is and to kill and kill until that world crumbles, even as the Twin Towers crumbled.

How shall we answer them? With blood and iron, of course, that being our only common language. But those whose privilege it is to make art also have a simultaneous duty to magnify the beauty of the world that the killers hate.

How shall we answer them? With blood and iron, of course, that being our only common language. But those whose privilege it is to make art also have a simultaneous duty to magnify the beauty of the world that the killers hate.

This is something that I talked about last year when I turned my Bradley Award lecture into an essay called “Confessions of an Aesthete”:

Yet art does indeed have a greater purpose, one suggested in this pithy line from an essay by the American painter and art critic Fairfield Porter: “When I paint, I think that what would satisfy me is to express what Bonnard said Renoir told him: make everything more beautiful.” That is the point of being an aesthete. If, like the Taliban, you hate the world, then it follows that you will hate art as well, or at least distrust it. But if you love the world, you will find in art a way of magnifying (in the religious sense of the word) its beauties.

It happens that one of the three dozen pieces of art that Mrs. T and I own is a lithograph by Pierre Bonnard, a 1942 study of a naked woman bathing herself. The first thing that I did when I got back to our apartment was turn on the lights and look at “Femme assise dans sa baignoire.” We would not be allowed to hang it if we lived in a land ruled by the Taliban or their monstrous confrères, for it violates every imaginable tenet of their life-denying faith. Hence the two of us are prouder than ever to display it on our walls today.

It happens that one of the three dozen pieces of art that Mrs. T and I own is a lithograph by Pierre Bonnard, a 1942 study of a naked woman bathing herself. The first thing that I did when I got back to our apartment was turn on the lights and look at “Femme assise dans sa baignoire.” We would not be allowed to hang it if we lived in a land ruled by the Taliban or their monstrous confrères, for it violates every imaginable tenet of their life-denying faith. Hence the two of us are prouder than ever to display it on our walls today.

Classic Stage Company is mounting a rare American production of Ivan Turgenev’s A Month in the Country that I’ll be flying to New York to see at the end of January. Like most Russian writers, Turgenev is not widely known in this country, but Henry James knew and admired him and his work, and it was Turgenev who inspired this quintessentially Jamesian meditation on the duty of the aesthete:

Evil is insolent and strong; beauty enchanting but rare; goodness very apt to be weak; folly very apt to be defiant; wickedness to carry the day; imbeciles to be in great places, people of sense in small, and mankind generally, unhappy. But the world as it stands is no illusion, no phantasm, no evil dream of a night; we wake up to it again for ever and ever; we can neither forget it nor deny it nor dispense with it. We can welcome experience as it comes, and give it what it demands, in exchange for something which it is idle to pause to call much or little so long as it contributes to swell the volume of consciousness. In this there is mingled pain and delight, but over the mysterious mixture there hovers a visible rule, that bids us learn to will and seek to understand.

For what it’s worth, I, too, have chosen to dedicate my life to the cause of “swelling the volume of consciousness.” Though I claim no great courage in doing so, I hope that I will prove worthy if a time should ever come when I must defend that choice against those who believe that art is something to be tamed—or destroyed.

On Saturday I saw two friends and two Broadway shows. I returned to LaGuardia the next morning, took off my belt and shoes, and submitted to being patted down by a guard. Behind him I saw a TSA poster hanging on the airport wall. NEVER FORGET 9/11/2001, it said. Don’t worry, I thought. Then I got on the plane that whisked me back to Sanibel Island and Mrs. T, far from Ground Zero and 10 Rue Nicholas-Appert but still part of the beautiful world that the evil ones long to burn.

* * *

A scene from Christopher Nolan’s The Dark Knight::