“The most perfect caricature is that which, on a small surface, with the simplest means, most accurately exaggerates, to the highest point, the peculiarities of a human being, at his most characteristic moment in the most beautiful manner.”

Max Beerbohm, “The Spirit of Caricature”

Archives for 2014

All Hart

In today’s Wall Street Journal drama column, I review three New York openings, Act One, Of Mice and Men, and The Library. Here’s an excerpt.

* * *

Moss Hart’s “Act One” is the best Broadway memoir ever written, the stirring story of how a dirt-poor Bronx boy who grew up in a slum became a name-above-the-title playwright. The second half, which tells how the then-unknown Hart contrived to collaborate with George S. Kaufman, the Neil Simon of his day, on a 1930 comedy called “Once in a Lifetime” that made him rich and famous, is the stuff theatrical dreams are made of. Countless stage-struck youngsters have read it and resolved, however fleetingly, to do as he did.

It’s surprising that none of them ever tried to turn “Act One” into a play, but the failure of Dore Schary’s lead-footed 1963 film version doubtless explains why so beloved a book took so long to find its way to the stage. Now James Lapine, who is to Stephen Sondheim what Hart was to Kaufman, has shouldered the task, both as writer and director. Unlike Schary, though, he’s chosen to adapt all of “Act One,” starting not with “Once in a Lifetime” but with Hart’s sad childhood. The result is a thrillingly well-staged play that runs for two hours and 40 minutes but feels much shorter. Not only is “Act One” light on its theatrical feet, but it has the open-hearted impact of a melodrama–one that has the advantage of being true.

It’s surprising that none of them ever tried to turn “Act One” into a play, but the failure of Dore Schary’s lead-footed 1963 film version doubtless explains why so beloved a book took so long to find its way to the stage. Now James Lapine, who is to Stephen Sondheim what Hart was to Kaufman, has shouldered the task, both as writer and director. Unlike Schary, though, he’s chosen to adapt all of “Act One,” starting not with “Once in a Lifetime” but with Hart’s sad childhood. The result is a thrillingly well-staged play that runs for two hours and 40 minutes but feels much shorter. Not only is “Act One” light on its theatrical feet, but it has the open-hearted impact of a melodrama–one that has the advantage of being true.

Part of what makes “Act One” so potent is that Mr. Lapine disdains all irony in describing Hart’s rise to fame. His was an old-fashioned American-dream-come-true tale, and it doesn’t embarrass Mr. Lapine in the least to dish it up on a pageant-like scale reminiscent of the spectacular stage version of “Nicholas Nickleby.” (It would also have made a great musical.) “Act One” is played out on a triple-decker revolving stage designed by Beowulf Boritt that catapults the 22 members of the cast from the Hart family’s tenement apartment to Kaufman’s Manhattan townhouse with cinematic speed….

It isn’t surprising that “Of Mice and Men” works better on the stage than the page. John Steinbeck always envisioned his dialogue-intensive book as (in his phrase) “a play that can be read or a novel that can be played,” and the fable-like tragedy of George (James Franco), an itinerant California farm worker, and Lennie (Chris O’Dowd), the simple-minded, pitifully innocent near-giant with whom he travels from job to job, gains immeasurably from theatrical presentation. The trick is to do it simply, and Anna D. Shapiro’s staging leaves nothing to be desired in that department. Todd Rosenthal’s windblown set is as plain as a tumbleweed, and the supporting cast, led by the matchless Jim Norton (he plays Candy, the aging field hand whose dog gets shot), leads us to the inescapable disaster with hard authenticity.

If only Mr. Franco, one of Hollywood’s top teen heart-throbs, had had the modesty to realize that Broadway is the wrong place to make your professional stage debut! While he doesn’t embarrass himself, his acting is flat and unmodulated by comparison with that of his infinitely more accomplished colleagues…

Steven Soderbergh, who claims to have given up making movies, has now directed an Off-Broadway play by one of his cinematic collaborators. Scott Z. Burns’ “The Library” is a fictional docudrama about the aftermath of a high-school shooting. The premise is juicy: One of the survivors (Chloë Grace Moretz) is accused by another survivor (Daryl Sabara) of having told the shooter where several of her fellow students were hiding. And Mr. Burns doesn’t fall into the trap of preaching a ripped-from-the-headlines sermon: While the last scene does get a bit portentous, “The Library” steers clear of banal point-making. But he never breaks through the smooth quasi-factual surface of the desperate situations that he portrays, and so “The Library,” for all its evident seriousness of purpose, feels more like an unusually well-written “Law & Order” episode than a full-fledged play.

Though he has next to no stage experience, Mr. Soderbergh already has a firm grasp of the demands of his new medium…

* * *

Read the whole thing here.

The theatrical trailer for the 1963 film version of Act One:

Almanac: Paul Hindemith on teaching

“Myself, I cannot compose all the time. I don’t get ideas just sitting around waiting for them. They come from somewhere, and I get them teaching.”

Paul Hindemith (quoted in the Harvard Crimson, Nov. 29, 1949)

So you want to see a show?

Here’s my list of recommended Broadway, off-Broadway, and out-of-town shows, updated weekly. In all cases, I gave these shows favorable reviews (if sometimes qualifiedly so) in The Wall Street Journal when they opened. For more information, click on the title.

BROADWAY:

• Bullets Over Broadway (musical, PG-13, reviewed here)

• A Gentleman’s Guide to Love & Murder (musical, PG-13, reviewed here)

• Matilda (musical, G, nearly all performances sold out last week, reviewed here)

• Les Misérables (musical, G, too long and complicated for young children, nearly all performances sold out last week, reviewed here)

• Once (musical, G/PG-13, reviewed here)

• A Raisin in the Sun (drama, G/PG-13, all performances sold out last week, reviewed here)

• Rocky (musical, G/PG-13, reviewed here)

OFF BROADWAY:

• Avenue Q (musical, R, adult subject matter and one show-stopping scene of puppet-on-puppet sex, reviewed here)

• The Fantasticks (musical, G, suitable for children capable of enjoying a love story, reviewed here)

• The Heir Apparent (verse comedy, PG-13, closes May 4, reviewed here)

CLOSING SOON OFF BROADWAY:

• London Wall (serious comedy, PG-13, newly extended through Apr. 26, reviewed here)

Almanac: Paul Hindemith on creation and irrationality

“The ultimate reason for his humility will be the musician’s conviction that beyond all the rational knowledge he has amassed and all his dexterity as a craftsman there is a region of visionary irrationality in which the veiled secrets of art dwell, sensed but not understood, implored but not commanded, imparting but not yielding. He cannot enter this region, he can only pray to be elected one of its messengers.”

Paul Hindemith, A Composer’s World: Horizons and Limitations

Snapshot: Glenn Gould plays Hindemith

Glenn Gould plays the fugue from Paul Hindemith’s Third Piano Sonata:

(This is the latest in a series of arts-related videos that appear in this space each Monday and Wednesday.)

Almanac: Paul Hindemith on composition

“The road from the head to the hand is a long one while one is still conscious of it. The man who does not so control his hand as to maintain it in unbroken contact with his thought does not know what composition is. (Nor does he whose well-routined hand runs along without any impulse or feeling behind it.”

Paul Hindemith, The Craft of Musical Composition

First time’s a charm

I first heard the music of Benjamin Britten in 1975, a year before he died. I was a sophomore music major at William Jewell College, a school not far from Kansas City. Some long-forgotten magazine piece–probably a review in High Fidelity or Stereo Review, to both of which I subscribed–had made me curious about him, so I drove to a mall in Independence and bought an LP whose first side contained a performance of the Serenade for Tenor, Horn, and Strings by Peter Pears, Barry Tuckwell, and the London Symphony Orchestra. Britten himself was the conductor. The recording was made in 1963, twenty years after the piece was written, and hearing it for the first time that evening was one of the most consequential musical encounters of my youth.

I first heard the music of Benjamin Britten in 1975, a year before he died. I was a sophomore music major at William Jewell College, a school not far from Kansas City. Some long-forgotten magazine piece–probably a review in High Fidelity or Stereo Review, to both of which I subscribed–had made me curious about him, so I drove to a mall in Independence and bought an LP whose first side contained a performance of the Serenade for Tenor, Horn, and Strings by Peter Pears, Barry Tuckwell, and the London Symphony Orchestra. Britten himself was the conductor. The recording was made in 1963, twenty years after the piece was written, and hearing it for the first time that evening was one of the most consequential musical encounters of my youth.

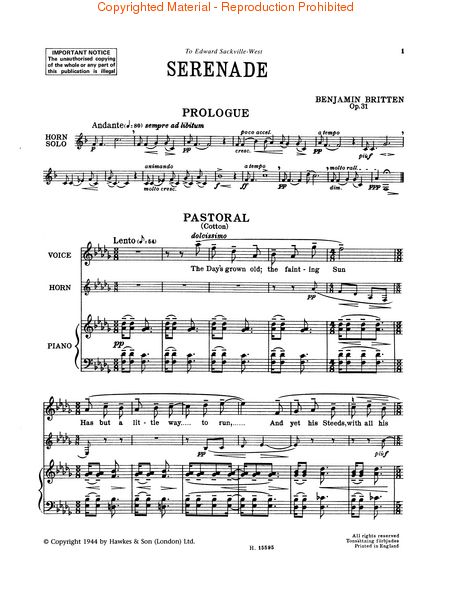

The Serenade starts off with a mysterious-sounding unaccompanied horn solo, followed by a setting of part of The Evening Quatrains, a lyric by Charles Cotton, a near-forgotten seventeenth-century English writer. Britten cut the poem in half and called his shortened version “Pastoral”:

The day’s grown old; the fainting sun

Has but a little way to run,

And yet his steeds, with all his skill,

Scarce lug the chariot down the hill.

The shadows now so long do grow,

That brambles like tall cedars show;

Mole hills seem mountains, and the ant

Appears a monstrous elephant.

A very little, little flock

Shades thrice the ground that it would stock;

Whilst the small stripling following them

Appears a mighty Polypheme.

And now on benches all are sat,

In the cool air to sit and chat,

Till Phoebus, dipping in the West,

Shall lead the world the way to rest.

Rarely in my life have I been so instantaneously overwhelmed as I was by “Pastoral,” though a few more years would go by before I attained sufficient musical sophistication to be able to fully understand why it had hit me so hard. It doesn’t look like much on the page, just a simple tune shared by the singer and horn player, accompanied by four-part string chords. Yet those deceptively uncomplicated-looking chords are anything but straightforward. Here as in his other middle-period masterpieces, Britten used tonal harmony with a piquant freshness and sense of surprise that were all his own.

Rarely in my life have I been so instantaneously overwhelmed as I was by “Pastoral,” though a few more years would go by before I attained sufficient musical sophistication to be able to fully understand why it had hit me so hard. It doesn’t look like much on the page, just a simple tune shared by the singer and horn player, accompanied by four-part string chords. Yet those deceptively uncomplicated-looking chords are anything but straightforward. Here as in his other middle-period masterpieces, Britten used tonal harmony with a piquant freshness and sense of surprise that were all his own.

“I need more chords,” Aaron Copland complained to Leonard Bernstein toward the end of his composing career. “I’ve run out of chords.” To listen to “Pastoral” is to realize that there will always be enough chords. All you have to do is know where to look.

These opening bars remind me of something that Britten said a year after he recorded the Serenade:

What is important in the arts is not the scientific part, the analyzable part of music, but the something which emerges from it but transcends it, which cannot be analyzed because it is not in it, but of it. It is the quality which cannot be acquired by simply the exercise of a technique or a system: it is something to do with personality, with gift, with spirit. I quite simply call it–magic: a quality which would appear to be by no means unacknowledged by scientists, and which I value more than any other part of music.

Back then I was still grabbing at classical music with both hands, and few weeks passed without my making a major discovery of some kind or other, most of which turned out before long to be…well, something less than major. But I was certain that my discovery of the magical “Pastoral” was more than just another passing fancy. It spoke to me, as did the rest of the Serenade, with a directness and immediacy not unlike the miraculous sensation of falling in love at first sight (something that had yet to happen to me). I knew beyond doubt that whoever Benjamin Britten was, his music would henceforth play an important part in my life–and so it did, and does.

Years later Britten’s 1963 recording of the Serenade for Tenor, Horn, and Strings would become one of the very first compact discs that I bought. Not only do I still have that CD, but I played it for Mrs. T last night, and she was as thunderstruck by her first hearing of the Serenade as I was thirty-nine years ago.

Years later Britten’s 1963 recording of the Serenade for Tenor, Horn, and Strings would become one of the very first compact discs that I bought. Not only do I still have that CD, but I played it for Mrs. T last night, and she was as thunderstruck by her first hearing of the Serenade as I was thirty-nine years ago.

“Why haven’t you played this for me until now?” she asked.

“I guess I just didn’t think to,” I replied with a touch of embarrassment. “But I’m glad I finally got around to it.”

* * *

Ian Bostridge, Radovan Vlatkovic, and the Norwegian Chamber Orchestra perform the prologue and “Pastoral” from Britten’s Serenade for Tenor, Horn, and Strings: