“We are all vainer of our luck than of our merits.”

“We are all vainer of our luck than of our merits.”

Rex Stout, The Rubber Band

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City

In honor of the great day when Louis Armstrong’s recording of “Hello, Dolly!” knocked the Beatles off the top of the pop charts, John Marchese of the New York Times has written a nifty little piece for that paper called “Back Where He Belonged: An All-Satchmo Day”:

In honor of the great day when Louis Armstrong’s recording of “Hello, Dolly!” knocked the Beatles off the top of the pop charts, John Marchese of the New York Times has written a nifty little piece for that paper called “Back Where He Belonged: An All-Satchmo Day”:

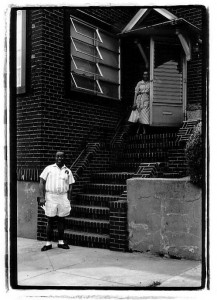

Maybe it was the 50th anniversary of “Hello, Dolly” having knocked the Beatles off the top of the pop charts (May 9, 1964), but it occurred to me recently that with a little advance work, I could spend an entire day in New York with Louis Armstrong.

Yes, I know, that idea seems absurd at first. Even a devoted fan like me has to acknowledge that as much as his music lives on, Armstrong, the renowned jazz musician and beloved entertainer known worldwide as Satchmo, died on July 6, 1971.

But he died in his sleep in the king-size bed on the second floor of his modest brick-clad house on 107th Street in Corona, Queens. His widow, Lucille, eventually left the house to the city, and it has been preserved largely as it was in his last days—right down to a bathrobe and a pair of slippers—and is open to the public six days a week. That would be my first stop….

And his last stop? A performance of Satchmo at the Waldorf, of course.

Read the whole thing here.

In today’s Wall Street Journal I report on two classical revivals in New York and the Chicago area, Kenneth Branagh’s Macbeth and Writers Theatre’s The Dance of Death. Here’s an excerpt.

* * *

The beloved buzzword of postmodern theater is “immersive.” In practice it can mean many different things, all of which reduce to one big thing: The audience is somehow made to feel as though it’s part of the show. In Kenneth Branagh’s “Macbeth,” for instance, you arrive at the Park Avenue Armory, present your ticket at the door and are duly assigned to a “clan” (complete with identifying rubber wrist band) and steered to a waiting area. In due course you and your fellow clan members are escorted across a gloomy simulacrum of Shakespeare’s “blasted heath” and seated in the appropriate section of two four-story-high tiers of comfortless bleachers that flank a long, narrow dirt-floored arena with Stonehenge-like monuments planted at either end. The play is then acted out in the arena.

The whole thing looks spectacular, just as it’s meant to, and the opening battle scene, which takes place in a torrential rainstorm that fills the arena with mud, is positively cinematic in its effect, right down to Patrick Doyle’s clamorous Hollywood-style musical score. From then on, though, this “Macbeth,” co-directed by Rob Ashford and Mr. Branagh, becomes earthbound and unpoetically literal. The clumsily conceived playing area, designed by Christopher Oram, is a big part of the problem, maybe even most of it: You feel as though you’re spending two intermissionless hours watching a play being performed in a drainage ditch, with the actors forced to alternately yell and trot from one end to the other….

The whole thing looks spectacular, just as it’s meant to, and the opening battle scene, which takes place in a torrential rainstorm that fills the arena with mud, is positively cinematic in its effect, right down to Patrick Doyle’s clamorous Hollywood-style musical score. From then on, though, this “Macbeth,” co-directed by Rob Ashford and Mr. Branagh, becomes earthbound and unpoetically literal. The clumsily conceived playing area, designed by Christopher Oram, is a big part of the problem, maybe even most of it: You feel as though you’re spending two intermissionless hours watching a play being performed in a drainage ditch, with the actors forced to alternately yell and trot from one end to the other….

A simpler and far less costly way to make any play “immersive” is to do it in a tiny theater. Writers Theatre does just that each time it presents a show in its 56-seat performance space, in which every member of the audience is within arm’s length of the actors. To see August Strindberg’s “The Dance of Death” in such tight quarters is likely to be a terrifying experience irrespective of the merits of the production—and this one, directed by Henry Wishcamper and performed in Conor McPherson’s suitably blunt English-language adaptation, is as good as it can possibly be.

Mr. McPherson has compressed “The Dance of Death” into a three-person chamber play about Alice and Edgar (Shannon Cochran and Larry Yando), a disillusioned married couple who snip, snipe, sneer and hack away at one another all night long, diverted from their mutual hostilities only by an unwelcome visit from an old friend (Philip Earl Johnson). The insults fly like shrapnel, and it is only at play’s end that you realize that these pathetic creatures know no other way to express their twisted love for one another.

It’s a potent theatrical conceit (enough so that Strindberg’s play served Edward Albee as the obvious model for “Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?”) that has long been catnip to first-class actors. Ms. Cochran and Mr. Yando are all that and more….

* * *

Read the whole thing here.

An excerpt from the Writers’ Theatre production of The Dance of Death:

In today’s Wall Street Journal drama column I write about two autobiographies, Stefan Zweig’s The World of Yesterday and Peter Drucker’s Adventures of a Bystander, whose similarities appear not to have been hitherto remarked. Here’s an excerpt.

* * *

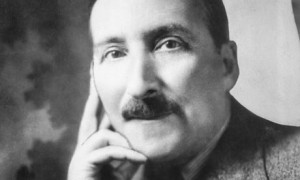

Sometimes all it takes is a movie. Stefan Zweig, a best-selling Austrian novelist who dropped off the Fame-O-Meter within a few years of his death in 1942, was catapulted back into the spotlight when Wes Anderson acknowledged that “The Grand Budapest Hotel,” his latest film, was inspired by Zweig’s books, and in particular by “The World of Yesterday,” the memoir in which he described the long-lost European culture into which he had been born six decades earlier. All at once it seemed that every magazine I read contained yet another excited essay about Zweig, and new paperback reissues of his out-of-print books started selling like…well, popcorn.

Sometimes all it takes is a movie. Stefan Zweig, a best-selling Austrian novelist who dropped off the Fame-O-Meter within a few years of his death in 1942, was catapulted back into the spotlight when Wes Anderson acknowledged that “The Grand Budapest Hotel,” his latest film, was inspired by Zweig’s books, and in particular by “The World of Yesterday,” the memoir in which he described the long-lost European culture into which he had been born six decades earlier. All at once it seemed that every magazine I read contained yet another excited essay about Zweig, and new paperback reissues of his out-of-print books started selling like…well, popcorn.

I, too, jumped on the bandwagon earlier this week. Though I’d always meant to read “The World of Yesterday,” I didn’t get around to it until “The Grand Budapest Hotel” brought Zweig back to mind. So I bought a copy and found myself swept up in his darkly nostalgic portrait of the self-confident, self-deluded culture of “security and creative reason” that was blown to bits by Adolf Hitler’s storm troopers. I didn’t get very far into the book, though, before I was struck by something else: “The World of Yesterday” is strikingly similar in both structure and tone to “Adventures of a Bystander,” Peter F. Drucker’s 1979 autobiography.

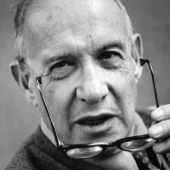

Most people remember Drucker, a longtime contributor to the Journal who died in 2005, as the most influential management consultant of the 20th century. What they may not know is that like Zweig, he was born in Austria and fled from the Nazis when Hitler came to power. What’s more, Drucker’s memories of prewar Vienna, which he compared in “Adventures of a Bystander” to Atlantis, Plato’s imaginary island paradise that fell from favor with the gods and disappeared into the Atlantic Ocean, are no less richly evocative than those in “The World of Yesterday.” And just as Zweig tells of his unforgettable encounters with such artists as Rainer Maria Rilke, Auguste Rodin and Arturo Toscanini, so is Drucker’s book largely devoted to indelible sketches of the fascinating men and women whom he met in the first half of his long life, who ranged from the great classical pianist Artur Schnabel to Henry Luce, the founder of Time magazine.

The obvious difference between the two books is that one was written by a novelist and the other by a political philosopher (insofar as a single phrase can describe Peter Drucker). But Drucker, like Zweig, was a cultivated émigré with a passionate interest in the fine arts, and the Europe that he describes in “Adventures of a Bystander,” a carefree, culture-besotted place without passports in which people moved freely from country to country, fancying themselves citizens of the universe, is all but indistinguishable from the one portrayed by Zweig…

The obvious difference between the two books is that one was written by a novelist and the other by a political philosopher (insofar as a single phrase can describe Peter Drucker). But Drucker, like Zweig, was a cultivated émigré with a passionate interest in the fine arts, and the Europe that he describes in “Adventures of a Bystander,” a carefree, culture-besotted place without passports in which people moved freely from country to country, fancying themselves citizens of the universe, is all but indistinguishable from the one portrayed by Zweig…

* * *

Read the whole thing here.

The theatrical trailer for The Grand Budapest Hotel:

Here’s my list of recommended Broadway, off-Broadway, and out-of-town shows, updated weekly. In all cases, I gave these shows favorable reviews (if sometimes qualifiedly so) in The Wall Street Journal when they opened. For more information, click on the title.

BROADWAY:

• Bullets Over Broadway (musical, PG-13, reviewed here)

• Cabaret (musical, PG-13/R, nearly all performances sold out last week, closes Jan. 4, reviewed here)

• The Cripple of Inishmaan (serious comedy, PG-13, reviewed here)

• A Gentleman’s Guide to Love & Murder (musical, PG-13, all performances sold out last week, reviewed here)

• Matilda (musical, G, most performances sold out last week, reviewed here)

• Les Misérables (musical, G, too long and complicated for young children, many performances sold out last week, reviewed here)

• Of Mice and Men (drama, PG-13, nearly all performances sold out last week, reviewed here)

• Once (musical, G/PG-13, reviewed here)

• A Raisin in the Sun (drama, G/PG-13, all performances sold out last week, reviewed here)

• Rocky (musical, G/PG-13, reviewed here)

OFF BROADWAY:

• The Fantasticks (musical, G, suitable for children capable of enjoying a love story, reviewed here)

IN CHICAGO:

• Juno (musical, PG-13, closes July 27, reviewed here)

IN GLENCOE, ILL.:

• Days Like Today (musical, PG-13, closes July 13, reviewed here)

CLOSING SOON OFF BROADWAY:

• Casa Valentina (drama, PG-13, closes June 29, reviewed here)

CLOSING SOON IN EAST HADDAM, CONN.:

• Damn Yankees (musical, G, closes June 21, reviewed here)

CLOSING NEXT WEEK IN CAMBRIDGE, MASS.:

• The Tempest (Shakespeare, G, closes June 15, reviewed here)

CLOSING NEXT WEEK ON BROADWAY:

CLOSING NEXT WEEK ON BROADWAY:

• Act One (drama, G, too long for children, closes June 15, reviewed here)

CLOSING SATURDAY AND SUNDAY IN WASHINGTON, D.C.:

• Henry IV, Parts One and Two (Shakespeare, PG-13, playing in rotating repertory, reviewed here)

CLOSING SATURDAY OFF BROADWAY:

• A Loss of Roses (drama, PG-13, reviewed here)

CLOSING SUNDAY IN CHICAGO:

• M. Butterfly (drama, PG-13, reviewed here)

Ethel Merman sings “Some People” (from Gypsy, by Jule Styne and Stephen Sondheim) on The Hollywood Palace in 1966, followed by a duet medley in which she is joined by Fred Astaire. This is the only time that Merman and Astaire ever performed together in public:

Ethel Merman sings “Some People” (from Gypsy, by Jule Styne and Stephen Sondheim) on The Hollywood Palace in 1966, followed by a duet medley in which she is joined by Fred Astaire. This is the only time that Merman and Astaire ever performed together in public:

(This is the latest in a series of arts-related videos that appear in this space each Monday and Wednesday.)

| M | T | W | T | F | S | S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | ||||

| 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

| 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 |

| 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 |

| 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 | |

An ArtsJournal Blog