Julian Bream plays two movements from William Walton’s Five Bagatelles in 1977:

Julian Bream plays two movements from William Walton’s Five Bagatelles in 1977:

(This is the latest in a series of arts-related videos that appear in this space each Monday and Wednesday.)

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City

I work at home in a small office-bedroom whose third-floor window looks down on a quiet, tree-lined block of Upper West Side brownstones. The window is to my left, a clothes closet to my right, and over the closet is a sleeping loft. (The ceilings in my apartment are unusually high.) The walls are white, the furniture black, the rug black and tan. I sit on a cheap, creaky swivel chair. My desk is one of those Danish-style slab-and-tube jobs: four shelves, no drawers. The shelf on which I work holds my iBook, a pair of good-quality desktop speakers hooked up to the computer (I often listen to music while I write), a phone-fax-answering machine, an external zip drive, and a tall, sometimes shaky stack of review CDs….

Read the whole thing here.

“O sacred solitary empty mornings, tranquil meditation—fruit of book-case and clock-tick, of note-book and arm-chair; golden and rewarding silence, influence of sun-dappled plane-trees, far-off noises of birds and horses, possessions beyond price of a few cubic feet of air and an hour of leisure! This vacuum of peace is the state from which art should proceed, for art is made by the alone for the alone.”

“O sacred solitary empty mornings, tranquil meditation—fruit of book-case and clock-tick, of note-book and arm-chair; golden and rewarding silence, influence of sun-dappled plane-trees, far-off noises of birds and horses, possessions beyond price of a few cubic feet of air and an hour of leisure! This vacuum of peace is the state from which art should proceed, for art is made by the alone for the alone.”

Cyril Connolly, The Unquiet Grave

One of my best friends has a southern accent. It’s strong but not overpowering—a scent, not a sauce—and I find it endearing, partly because my friend is a very dear person and partly because the way she talks reminds me of how people talk back where I come from.

I lost my own accent (most of it, anyway) when I moved to New York, and for a long time I took it for granted that all such distinctive regional accents were destined to vanish sooner or later, most likely the former. When I first read John Steinbeck’s Travels With Charley, the 1962 book in which the author of The Grapes of Wrath described a trip across America that he took in a camper, I was struck by the oft-quoted passage in which he predicted the eventual disappearance of regional American accents, a passage that I took at the time to have the irresistible force of prophecy.

I lost my own accent (most of it, anyway) when I moved to New York, and for a long time I took it for granted that all such distinctive regional accents were destined to vanish sooner or later, most likely the former. When I first read John Steinbeck’s Travels With Charley, the 1962 book in which the author of The Grapes of Wrath described a trip across America that he took in a camper, I was struck by the oft-quoted passage in which he predicted the eventual disappearance of regional American accents, a passage that I took at the time to have the irresistible force of prophecy.

I had occasion to quote part of it six years ago in this space, but now I want to quote a different part:

One of my purposes was to listen, to hear speech, accent, speech rhythms, overtones and emphasis. For speech is so much more than words and sentences. I did listen everywhere. It seemed to me that regional speech is in the process of disappearing, not gone but going. Forty years of radio and twenty years of television must have this impact. Communications must destroy localness, by a slow, inevitable process….Just as our bread, mixed and baked, packaged and sold without benefit of accent or human frailty, is uniformly good and uniformly tasteless, so will our speech become one speech.

Like most such ripe, resonant, and perfectly plausible-sounding predictions, this one has failed to hold water. Just as the Connecticut grocery store where Mrs. T and I shop now stocks every imaginable kind of bread, all of it edible and some delectable, so does American regional speech continue to prosper well into the twenty-first century, more than fifty years after Steinbeck proclaimed its inexorable demise. Even now, folks talk different ways in different parts of the country, and many of them, like my friend, keep on talking the same way after they move to new parts. Nor do they see any reason to change just because they happen to hear different accents on TV.

Living in Manhattan as I do, I don’t normally hear southern accents in the course of an ordinary day, unless I specifically seek them out by listening to country music. But I don’t have to do that in order to imagine them, and I like knowing that they’re still routinely to be heard back where I come from, just like the train whistles that the residents of Smalltown, U.S.A., can still hear wailing in the distance at odd intervals throughout the day and night, even as I heard them throughout my boyhood.

Duke Ellington liked train whistles, too, as you can hear for yourself in Daybreak Express, his 1933 musical portrait of an express train, and as Richard O. Boyer recorded for posterity in The Hot Bach, his 1944 New Yorker profile of Ellington:

Duke Ellington liked train whistles, too, as you can hear for yourself in Daybreak Express, his 1933 musical portrait of an express train, and as Richard O. Boyer recorded for posterity in The Hot Bach, his 1944 New Yorker profile of Ellington:

Ellington always feels that he has found sanctuary when he boards a train. He says that then peace descends upon him and that the train’s metallic rhythm soothes him. He likes to hear the whistle up ahead, particularly at night, when it screeches through the blackness as the train gathers speed. “Specially in the South,” he says. “There the firemen play blues on the engine whistle—big, smeary things like a goddam woman singing in the night.”

For those of us who miss and revere the lost worlds of our youth, such sounds, whether heard or remembered, are a comfort and an inspiration. “The memory of things gone is important to a jazz musician,” Ellington told Boyer. “Things like the old folks singing in the moonlight in the back yard on a hot night, or something someone said long ago.” Or the midsummer crickets that I hear in my mind’s ear whenever I listen to my friend talking about anything at all.

“Humility is not a virtue propitious to the artist. It is often pride, emulation, avarice, malice—all the odious qualities—which drive a man to complete, elaborate, refine, destroy, renew, his work until he has made something that gratifies his pride and envy and greed. And in doing so he enriches the world more than the generous and good, though he may lose his own soul in the process. That is the paradox of artistic achievement.”

“Humility is not a virtue propitious to the artist. It is often pride, emulation, avarice, malice—all the odious qualities—which drive a man to complete, elaborate, refine, destroy, renew, his work until he has made something that gratifies his pride and envy and greed. And in doing so he enriches the world more than the generous and good, though he may lose his own soul in the process. That is the paradox of artistic achievement.”

Evelyn Waugh, review of Garry Wills’ Chesterton: Man and Mask (courtesy of Patrick Kurp)

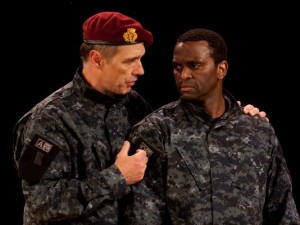

The Wall Street Journal isn’t publishing a print version today, but my Friday drama column appears as usual online. Today I report on the Hudson Valley Shakespeare Festival’s production of Othello. Here’s an excerpt.

* * *

“Othello” is about many things, but one of them is (very obviously) race. You’d think, then, that Shakespeare’s harrowing tale of the jealous Moor and his innocent white wife would bring out the worst in postmodern stage directors, many of whom are reflexively predisposed to hammer any such hot button deep into the ground. And you’d be wrong, at least in my experience: None of the five “Othellos” that I’ve reviewed in this space since 2005 was explicitly political in its approach. Neither is Christopher V. Edwards’ new Hudson Valley Shakespeare Festival production, a hard-nosed, hard-hitting modern-dress version that goes straight to the point—jealousy—and stays there….

The acting is naturalistic, the violence blunt and believable, and it isn’t hard to conjure up convincing backstories for the main characters. Mr. Lowe’s Othello could easily be a physically slight ghetto kid who joined the Army to escape the street and made himself over into a straight-arrow soldier. As for Mr. Rhoads’ regular-guy Iago, he’s an equally familiar type, a gray-at-the-temples wheelhorse who got passed over for promotion and now finds himself taking orders from a hotshot with a pretty young wife (Susannah Millonzi). He’s not oily, not sinister, not oozing with snarly malevolence: All he wants is what he thinks he’s got coming to him, and he’ll do whatever he has to do to get it. Such everyday conflicts are the stuff of which everyday murders are made.

The acting is naturalistic, the violence blunt and believable, and it isn’t hard to conjure up convincing backstories for the main characters. Mr. Lowe’s Othello could easily be a physically slight ghetto kid who joined the Army to escape the street and made himself over into a straight-arrow soldier. As for Mr. Rhoads’ regular-guy Iago, he’s an equally familiar type, a gray-at-the-temples wheelhorse who got passed over for promotion and now finds himself taking orders from a hotshot with a pretty young wife (Susannah Millonzi). He’s not oily, not sinister, not oozing with snarly malevolence: All he wants is what he thinks he’s got coming to him, and he’ll do whatever he has to do to get it. Such everyday conflicts are the stuff of which everyday murders are made.

Mr. Rhoads dominates the scenes that he shares with Mr. Lowe, and that’s as it should be. This is, after all, a staging in which Othello really is the “credulous fool” that Iago takes him to be, a basically good guy who never knew what hit him until it was too late. But it’s Ms. Millonzi who brings home the prize. She appeared three summers ago in a Shakespeare & Company production of “Romeo and Juliet” in which she played Juliet as a sullen woman-child ablaze with the fires of love. She hews to a similar line here, turning Desdemona into a fully sexual being who is hopelessly smitten with her handsome husband—which makes his dizzying descent into madness all the more horrifying…

* * *

Read the whole thing here.

| M | T | W | T | F | S | S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | ||||

| 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

| 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 |

| 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 |

| 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 | |

An ArtsJournal Blog