Jonathan Winters improvises on a 1964 episode of The Jack Paar Program, using a stick as his only prop:

Jonathan Winters improvises on a 1964 episode of The Jack Paar Program, using a stick as his only prop:

(This is the latest in a series of arts-related videos that appear in this space each Monday and Wednesday.)

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City

In today’s Wall Street Journal I file the second of two consecutive reports from Ontario’s Shaw Festival, this one about a pair of important revivals, Edward Bond’s The Sea and Philip Barry’s The Philadelphia Story. Here’s an excerpt.

* * *

Prolific and controversial in equal measure, Britain’s Edward Bond is esteemed in France but rarely performed in his native land, much less on this side of the Atlantic. Hence Canada’s Shaw Festival, which is best known for producing plays by George Bernard Shaw and his contemporaries, has done the English-speaking theater a signal service by reviving “The Sea,” Mr. Bond’s 1973 “comedy” (that’s what he calls it, anyway) about a seaside village run by a rich, imperious old gorgon (Fiona Reid) whose high-handed behavior has turned one of the locals (Patrick Galligan) into a conspiracy theorist of the wilder-eyed variety—an Edwardian John Bircher, if you will, who hides his lunacy behind a village shopkeeper’s cringing obsequiousness.

Mr. Bond, in the manner of most modern British playwrights, is a man of the left, and “The Sea,” which dates from the dawning of the Age of Thatcher, can be read as a portrait of class warfare among the provincials. But like Shaw and Bertolt Brecht, his masters, Mr. Bond is too much the artist to content himself with coarse ideological parallels. Instead he turns his imagination loose, and the result is a midnight-black comedy that whipsaws the viewer between uproarious small-town satire and a stoicism so bleak and astringent (“The years go very quickly and you seem to be spared the minutes”) that it makes your skin tingle.

Mr. Bond, in the manner of most modern British playwrights, is a man of the left, and “The Sea,” which dates from the dawning of the Age of Thatcher, can be read as a portrait of class warfare among the provincials. But like Shaw and Bertolt Brecht, his masters, Mr. Bond is too much the artist to content himself with coarse ideological parallels. Instead he turns his imagination loose, and the result is a midnight-black comedy that whipsaws the viewer between uproarious small-town satire and a stoicism so bleak and astringent (“The years go very quickly and you seem to be spared the minutes”) that it makes your skin tingle.

Eda Holmes’ staging is nothing short of remarkable, a small-scale presentation so tightly unified and subtly poetic as to recall David Cromer’s landmark revival of “Our Town.” As for Mr. Galligan, his acting is at once comically demented and utterly terrifying, a mixture that’s guaranteed to chill you…

Philip Barry’s sky-high comedies of white-shoe manners used to be box-office magic. But his reputation took a nosedive after his death in 1949, and not only have none of his plays received a major production in this country since 1995, but only two of them, “Holiday” and “The Philadelphia Story,” have ever been revived on Broadway. I had to travel to Canada to finally see a Barry play: The Shaw Festival is giving “The Philadelphia Story” the deluxe treatment, with Moya O’Connell in the Katharine Hepburn-created part of Tracy Lord, the heiress-divorcée from Philadelphia’s Main Line who finds herself torn between three suitors, one of them her ex-husband (Gray Powell), on the eve of her second marriage.

Does “The Philadelphia Story” work onstage? Absolutely, enough so that I came away even more eager to see Barry’s other plays. What’s more, Dennis Garnhum’s staging is clear and confident, while William Schmuck’s triple-turntable set is positively spectacular. The problem is that George Cukor’s 1940 film version, in which Hepburn, Cary Grant and James Stewart were all in flawless form, is one of a handful of successful Hollywood adaptations of important American stage plays that closely track the scripts on which they’re based. Yes, it’s fascinating to see how well “The Philadelphia Story” plays in its original form, but you won’t learn much about it that you didn’t already know from having seen the movie….

* * *

To read my review of The Sea, go here.

To read my review of The Philadelphia Story, go here.

In today’s Wall Street Journal “Sightings” column, I consider the PBS Fall Arts Festival 2014. Here’s an excerpt.

* * *

Fifty years ago, New York’s fine-arts institutions set the tone for the arts in America to an extent that is unimaginable now. One of the reasons for their collective dominance, of course, was that some of them didn’t have a whole lot of competition: Regional dance, opera and theater were still in their cradles in 1964. But even the major regional museums and symphony orchestras that already existed in abundance had yet to become truly national institutions. In fact, most of them were all but unknown outside their home cities. Why? Because the national news media largely ignored their activities. Yes, the three commercial TV networks, not to mention Time and Life and Newsweek, devoted quite a bit of time and space to the fine arts in the early ‘60s—but they all operated out of Manhattan, and so they mostly concentrated on covering the great New York-based arts organizations with which they were surrounded.

Today you can find first-rate art from coast to coast—but the national media no longer cover the fine arts other than sporadically in New York, much less elsewhere in the U.S. That’s where PBS is supposed to come in. Its mandate, President Lyndon Johnson said, was “to enrich man’s spirit,” and throughout most of its history it did so by devoting a significant part of its schedule to the fine arts.

And how does it do so today? Last week PBS announced its new Arts Fall Festival lineup. Paula Kerger, the network’s president and CEO, has been playing it ultra-safe ever since, in 2011, she launched the Fall Festival, PBS’ flagship arts-programming venture. I surveyed the first year’s shows and found them to be “a stiff dose of the usual safety-first pledge-week fare.” I hoped back then that things might improve over time, but the entries for 2014 are even blander and more predictable….

And how does it do so today? Last week PBS announced its new Arts Fall Festival lineup. Paula Kerger, the network’s president and CEO, has been playing it ultra-safe ever since, in 2011, she launched the Fall Festival, PBS’ flagship arts-programming venture. I surveyed the first year’s shows and found them to be “a stiff dose of the usual safety-first pledge-week fare.” I hoped back then that things might improve over time, but the entries for 2014 are even blander and more predictable….

Note well what is missing from the Fall Festival lineup: It includes no ballet or modern dance, no classic theater, no real jazz, no opera save for “Porgy” and no classical music of any kind. Moreover, the nine programs barely hint at the nationwide scope of American art: Of the eight performance-based shows in the series, all but three were taped in New York….

* * *

Read the whole thing here.

To read the official press release announcing the PBS Fall Arts Festival 2014, go here.

Here’s my list of recommended Broadway, off-Broadway, and out-of-town shows, updated weekly. In all cases, I gave these shows favorable reviews (if sometimes qualifiedly so) in The Wall Street Journal when they opened. For more information, click on the title.

BROADWAY:

• Bullets Over Broadway (musical, PG-13, closes Aug. 24, reviewed here)

• Cabaret (musical, PG-13/R, nearly all performances sold out last week, closes Jan. 4, reviewed here)

• A Gentleman’s Guide to Love & Murder (musical, PG-13, all performances sold out last week, reviewed here)

• Matilda (musical, G, all performances sold out last week, reviewed here)

• Les Misérables (musical, G, too long and complicated for young children, nearly all performances sold out last week, reviewed here)

• Once (musical, G/PG-13, reviewed here)

OFF BROADWAY:

• The Fantasticks (musical, G, suitable for children capable of enjoying a love story, reviewed here)

IN GARRISON, N.Y.:

• The Liar (verse comedy, PG-13, closes Aug. 31, reviewed here)

• Othello (Shakespearean tragedy, PG-13, closes Aug. 30, reviewed here)

• Othello (Shakespearean tragedy, PG-13, closes Aug. 30, reviewed here)

• Two Gentlemen of Verona (Shakespearean comedy, PG-13, closes Aug. 29, reviewed here)

IN NIAGARA-ON-THE-LAKE, ONTARIO:

• Arms and the Man (comedy, G/PG-13, closes Oct. 18, reviewed here)

• When We Are Married (comedy, PG-13, closes Oct. 26, reviewed here)

CLOSING SOON ON BROADWAY:

• Rocky (musical, G/PG-13, closes Aug. 17, reviewed here)

CLOSING NEXT WEEK OFF BROADWAY:

• When We Were Young and Unafraid (drama, PG-13, closes Aug. 10, reviewed here)

CLOSING SUNDAY IN GLENCOE, ILL.:

• The Dance of Death (drama, PG-13, reviewed here)

“A conquering race, in the place of that conquest, is rarely amiable; the conquerors pay less obviously than the conquered, but perhaps in time they pay even more heavily, in the loss of the humane qualities. Hard, arrogant, profit-seeking adventurers flock to the spoil, and the natives, though outwardly civil, contemplate them with a resentment mingled with contempt, while at the same time respecting the face of conquest—acknowledging their greater strength.”

“A conquering race, in the place of that conquest, is rarely amiable; the conquerors pay less obviously than the conquered, but perhaps in time they pay even more heavily, in the loss of the humane qualities. Hard, arrogant, profit-seeking adventurers flock to the spoil, and the natives, though outwardly civil, contemplate them with a resentment mingled with contempt, while at the same time respecting the face of conquest—acknowledging their greater strength.”

Patrick O’Brian, The Mauritius Command

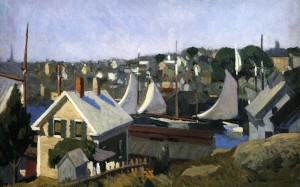

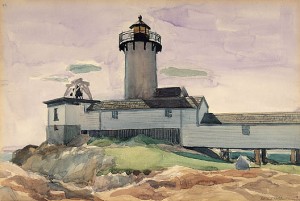

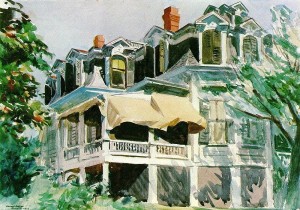

Mrs. T and I recently spent two tranquil days in Gloucester, the Massachusetts harbor town where Edward Hopper spent a fair amount of time in the Twenties and several of whose houses he famously painted. We asked the obliging woman at the front desk of our pretty seaside inn if there were any Hopper paintings or tours to be seen or taken in Gloucester. She looked at us with endearing blankness, as if we’d inquired about Le Nozze di Figaro, or quantum theory.

Mrs. T and I recently spent two tranquil days in Gloucester, the Massachusetts harbor town where Edward Hopper spent a fair amount of time in the Twenties and several of whose houses he famously painted. We asked the obliging woman at the front desk of our pretty seaside inn if there were any Hopper paintings or tours to be seen or taken in Gloucester. She looked at us with endearing blankness, as if we’d inquired about Le Nozze di Figaro, or quantum theory.

This encounter reminded me yet again of how insignificant a role the fine arts play in the lives of most people, and how little that matters in the greater scheme of things. Having grown up in a small town in the middle of America, I ought to know better than to think otherwise, but a quarter-century of continuous residence in Manhattan has inevitably blunted my sense of what matters most to the average American. Hint: it isn’t art.

Alas, aesthetes also have a way of forgetting that taste and virtue are not the same thing. To be sure, the poet-philosopher Friedrich Schiller, whose “Ode to Joy” was set to music by Beethoven as the finale of his Ninth Symphony, believed that “taste develops in the mind a fitness for virtue, because it suppresses the inclinations which impede, and rouses those which are favorable to virtue.” But I don’t know that I agree with him. In fact, I think that in America, something not unlike the opposite holds true, if only because the fact that our artists and intellectuals tend not to get much respect (or make much money) has a way of breeding ressentiment, the nastiest and most self-destructive of all emotions.

Alas, aesthetes also have a way of forgetting that taste and virtue are not the same thing. To be sure, the poet-philosopher Friedrich Schiller, whose “Ode to Joy” was set to music by Beethoven as the finale of his Ninth Symphony, believed that “taste develops in the mind a fitness for virtue, because it suppresses the inclinations which impede, and rouses those which are favorable to virtue.” But I don’t know that I agree with him. In fact, I think that in America, something not unlike the opposite holds true, if only because the fact that our artists and intellectuals tend not to get much respect (or make much money) has a way of breeding ressentiment, the nastiest and most self-destructive of all emotions.

As I observed in this space back in 2005, I live in

the genteel obscurity of a middle-to-highbrow critic who can count his network TV appearances on some of the fingers of one hand. I realized long ago that in America, there’s no such thing as a famous writer, only famous actors. My all-time favorite joke is about the, er, Polish starlet who, er, slept with the screenwriter. If I ever write a book about Hollywood, which isn’t likely, that’ll be the title: She Screwed the Writer. (Or something close to that, anyway.)

Do I wish I were rich and famous? Sometimes—though much less often than you’d think. But do I think I deserve to be rich and famous? Not even slightly. All things being equal, I do wish that everybody in America knew who Edward Hopper was, and that our public schools introduced their students to the greatest masterpieces of American art. But I don’t think it would necessarily make them better human beings to know who painted “The Mansard Roof,” or to be able to hum a few bars of the Copland Violin Sonata. At the risk of falling afoul of Godwin’s Law, I think it’s worth pointing out that the most vicious mass murderer of the twentieth century initially aspired to be a professional artist and took a serious and lasting interest in opera.

Do I wish I were rich and famous? Sometimes—though much less often than you’d think. But do I think I deserve to be rich and famous? Not even slightly. All things being equal, I do wish that everybody in America knew who Edward Hopper was, and that our public schools introduced their students to the greatest masterpieces of American art. But I don’t think it would necessarily make them better human beings to know who painted “The Mansard Roof,” or to be able to hum a few bars of the Copland Violin Sonata. At the risk of falling afoul of Godwin’s Law, I think it’s worth pointing out that the most vicious mass murderer of the twentieth century initially aspired to be a professional artist and took a serious and lasting interest in opera.

If I can be forgiven for quoting myself again, “Daily megadoses of beauty won’t make you a better person unless you were a good person to begin with.” Happier? Maybe. Better? No.

* * *

To hear Edward Hopper talking about “The Mansard Roof,” go here.

Louis Kaufman plays the first movement of Aaron Copland’s Violin Sonata, accompanied by the composer:

| M | T | W | T | F | S | S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | ||||

| 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

| 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 |

| 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 |

| 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 | |

An ArtsJournal Blog