“Government’s an affair of sitting, not hitting. You rule with the brains and the buttocks, never with the fists.”

“Government’s an affair of sitting, not hitting. You rule with the brains and the buttocks, never with the fists.”

Aldous Huxley, Brave New World

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City

I spent last week in Spring Green, the tiny Wisconsin village that is home to American Players Theatre, Frank Lloyd Wright’s Taliesin, Arcadia Books, and one of my best friends. I go there each summer for professional reasons—APT is the best classical theater company in America—but I’d very likely find an excuse to go even if there weren’t any shows to see, for it’s one of my favorite places. Whenever I drive through the cornfields, woodlands, and rolling hills that surround Spring Green, I find that other drivers on the road are constantly passing me by. It isn’t hard to see why. They have places to go, but I don’t, unless I happen to be on my way to the theater. All I ever want to do in Spring Green is be where I am.

I spent last week in Spring Green, the tiny Wisconsin village that is home to American Players Theatre, Frank Lloyd Wright’s Taliesin, Arcadia Books, and one of my best friends. I go there each summer for professional reasons—APT is the best classical theater company in America—but I’d very likely find an excuse to go even if there weren’t any shows to see, for it’s one of my favorite places. Whenever I drive through the cornfields, woodlands, and rolling hills that surround Spring Green, I find that other drivers on the road are constantly passing me by. It isn’t hard to see why. They have places to go, but I don’t, unless I happen to be on my way to the theater. All I ever want to do in Spring Green is be where I am.

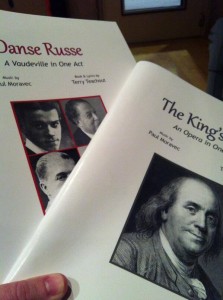

I appreciated my visit all the more because the season just past was more than usually rough on me, gratifying and exhausting in like measure. A new opera, a new book, the off-Broadway transfer of my first play: these things alone would have been enough to wear me out without taking into further consideration my day job and the various other stresses of my life.

So I treated my trip to Spring Green as something of a working vacation. I filed two Wall Street Journal columns before I left for Wisconsin so that I wouldn’t have to knock out any copy during my stay, and instead of bringing one of the various books about which I’m planning to write in the next couple of months, I packed a half-dozen undemanding novels. The trip, to be sure, was a bit of a slog, for it ended up taking me twelve hours to get from our place in Connecticut to the driveway of Spring Valley Inn, and I didn’t fall into bed until well after midnight. But no sooner did I awake the next day than I felt my troubles slipping from my shoulders, and in between American Buffalo, The Doctor’s Dilemma, The Seagull, and Travesties, I found more than enough time to unwind.

One of the books that I brought with me to Spring Green was William Haggard’s Venetian Blind, a spy novel whose cast of characters includes a Bonnard-loving industrial magnate who doesn’t know much about art but knows what he likes:

One of the books that I brought with me to Spring Green was William Haggard’s Venetian Blind, a spy novel whose cast of characters includes a Bonnard-loving industrial magnate who doesn’t know much about art but knows what he likes:

“I don’t disapprove of avant garde. I can’t, for I know nothing about it. But I confess I’m inclined to resent it.”

“Resent it?”

“Yes. I suspect it of trying to teach me something—to convert me. And I don’t want to be converted. I listen for relaxation, you know. Perhaps I’m not really a musical man. But I don’t want struggle or significance or purpose. I want to be pleased.”

Richard Wakeley, looking about the room, could agree….The walls were the palest of apple greens, the pilasters’ capitals discreetly gilded. It was a lovely room, calm and assured, a room for leisure and for formal good manners. Outside it men wrestled with eternal problems: evil and beauty, sin and solipsism. Sometimes the greater the problem the smaller the man. Enormous, insoluble problems. And quite possibly meaningless. Yes, in this lovely room almost certainly without meaning.

That’s not quite me, but it came pretty close last week. Instead of wrestling with the eternal and insoluble problems that are my customary lot, I allowed myself to relax into the present. I’m back on the East Coast now, reunited with Mrs. T and more than happy to be. Hectic and harassing though it sometimes is, I love my life and am at all times grateful for the increasingly improbable good fortune that permits me to make a living writing about the arts. But man cannot live by work alone, no matter how much he loves it, and so it was both good and necessary for me to slip the traces and spend a few days under the bright blue skies of Wisconsin, enjoying the restorative pleasures of doing nothing in particular.

That’s not quite me, but it came pretty close last week. Instead of wrestling with the eternal and insoluble problems that are my customary lot, I allowed myself to relax into the present. I’m back on the East Coast now, reunited with Mrs. T and more than happy to be. Hectic and harassing though it sometimes is, I love my life and am at all times grateful for the increasingly improbable good fortune that permits me to make a living writing about the arts. But man cannot live by work alone, no matter how much he loves it, and so it was both good and necessary for me to slip the traces and spend a few days under the bright blue skies of Wisconsin, enjoying the restorative pleasures of doing nothing in particular.

* * *

Mildred Bailey and the Delta Rhythm Boys sing Alec Wilder’s “It’s So Peaceful in the Country” in 1941:

I don’t have any illusions about All in the Dances. It’s a short critical biography of a great choreographer, not a philosophical treatise, and while I do think it’s a damned good book, I can’t imagine that it’ll be read a hundred years hence, nor would I dream of suggesting that its publication will help make the world a significantly better place. So why did I work so hard on it at what might reasonably have been thought to be an inappropriate time? Because I believe deeply in the ennobling sanctity of craft. Because I agree with Ecclesiastes’ preacher: Whatsoever thy hand findeth to do, do it with all thy might. Because it’s mine….

Read the whole thing here.

Michael Steinman, one of my favorite bloggers, recently posted something poignant about the central importance of music in his life:

Michael Steinman, one of my favorite bloggers, recently posted something poignant about the central importance of music in his life:

Although I am by nature optimistic and hopeful, before 2004 I was seriously unhappy for long periods of time—situational rather than biochemical despair. The reasons for my sadness are not relevant here. When I was most hopeless, I thought seriously of ending my life. I checked out the Hemlock Society website (earnest but very complicated) and lay on my bed thinking of the items I would purchase from Home Depot that would do the job.

But one thought recurred in the darkness, “Is there any guarantee you will be able to hear music—Louis Armstrong first and everyone else you love—if you kill yourself?” It kept me from putting my plans into action….

I’ve never felt suicidal, but beyond that I think I know exactly what Michael means. While I can, if absolutely necessary, imagine living without music, it would be like living without salt, or love. Kingsley Amis put it nicely when he wrote that “only a world without love strikes me as instantly and decisively more terrible than one without music. Yes, friendship would beat music too, but not instantly.” Indeed, I sometimes doubt that I could truly love a person to whom music wasn’t important—and wonder whether that might possibly be a failing on my part.

All that said, I also know that music is not the first priority in my life. If I had to choose between reading and listening to music, I’d choose reading—with extreme reluctance, to be sure, but without a shadow of doubt.

In a sense, I made that choice, or something close to it, when I decided to become a professional writer instead of continuing to pursue my budding career as a performing musician, splitting the difference by writing about music. Nevertheless, it was a clear-cut choice, and I know why I made it. For one thing, I was better at writing than at playing. At least as important, though, was my belated recognition that for all my passionate love of music, it simply didn’t occupy enough of my mind to satisfy my curiosity about the world. I was interested in too many other things, and I knew that I could write about all of them. To make a living making music, by contrast, is—must be—an all-consuming enterprise, and I wasn’t prepared to be consumed by it.

In a sense, I made that choice, or something close to it, when I decided to become a professional writer instead of continuing to pursue my budding career as a performing musician, splitting the difference by writing about music. Nevertheless, it was a clear-cut choice, and I know why I made it. For one thing, I was better at writing than at playing. At least as important, though, was my belated recognition that for all my passionate love of music, it simply didn’t occupy enough of my mind to satisfy my curiosity about the world. I was interested in too many other things, and I knew that I could write about all of them. To make a living making music, by contrast, is—must be—an all-consuming enterprise, and I wasn’t prepared to be consumed by it.

So I walked away from the bandstand, and though I’ve spent many an hour thinking about the choice I made, I’ve never thought twice about the wisdom of having made it. As I wrote in this space eight years ago in an essay about the last time I played bass in public:

Somebody asked me once if I were a frustrated musician. “No,” I said, “I’m a fulfilled writer.” But that doesn’t mean I never think about what might have been, much less what used to be. The way I feel about having once been a musician is not unlike the way some reformed alcoholics feel about booze. They know they can’t live with it anymore, but they also know how much they liked it, and they remember, as clearly as if it were this morning, how good that last drink tasted. I remember, too.

The point, of course, is that I wouldn’t have made that same choice if music had really been the most important thing in my life. Important it was, immensely so, but not that important—a near-run thing, but not quite.

Now I’m a full-time writer, and in the past few years I’ve also transformed myself into a part-time playwright and librettist, a pursuit that has become for me what music once was, only (you might say) more so. It allows me to be creative in a way that best suits my particular talents, as well as to collaborate with other artists in much the same way that I did when I was a musician. What’s more, writing operas has put me back in touch with the working world of music, which is both a blessing and a bonus.

Now I’m a full-time writer, and in the past few years I’ve also transformed myself into a part-time playwright and librettist, a pursuit that has become for me what music once was, only (you might say) more so. It allows me to be creative in a way that best suits my particular talents, as well as to collaborate with other artists in much the same way that I did when I was a musician. What’s more, writing operas has put me back in touch with the working world of music, which is both a blessing and a bonus.

Even so, it isn’t the same as being a musician—and that part of my life, I know, is over for good. The last time I picked up a bass and tried to play it, it was as though I were wearing a pair of mittens: I still remembered where to put my hands and what to do with them, but nothing felt or sounded right. From now on I will never be anything more than a listener, a person to whom music is immensely important but not, when all is said and done, indispensable.

Even now, it still feels strange to me to make this admission, to acknowledge that my identity underwent an essential transformation somewhere along the path of my life, that I am no longer the person I was when young. Stephen Sondheim captured part of the feeling in my favorite of his songs, “The Road You Didn’t Take”: The worlds I’ll never see/Still will be around,/Won’t they?/The Ben I’ll never be,/Who remembers him? But it’s not true: I remember him very well, and sometimes I miss him very, very much.

* * *

From 2000, George Hearn sings “The Road You Didn’t Take” (from Follies) in the Stephen Sondheim revue Putting It Together:

“Childe Hassam, Artist: A Short Personal Sketch,” a four-minute abridgement of a fifteen-minute silent educational film about the American Impressionist painter originally produced by the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1932. The painting on which Hassam can be seen working in the film is Long Island Pebbles and Fruit, completed in 1931 and now in the collection of the American Academy of Arts and Letters. Hassam died in 1935:

“Childe Hassam, Artist: A Short Personal Sketch,” a four-minute abridgement of a fifteen-minute silent educational film about the American Impressionist painter originally produced by the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1932. The painting on which Hassam can be seen working in the film is Long Island Pebbles and Fruit, completed in 1931 and now in the collection of the American Academy of Arts and Letters. Hassam died in 1935:

(This is the latest in a series of arts-related videos that appear in this space each Monday and Wednesday.)

“‘It’s curious,’ he went on after a little pause, ‘to read what people in the time of Our Ford used to write about scientific progress. They seemed to have imagined that it could be allowed to go on indefinitely, regardless of everything else. Knowledge was the highest good, truth the supreme value; all the rest was secondary and subordinate. True, ideas were beginning to change even then. Our Ford himself did a great deal to shift the emphasis from truth and beauty to comfort and happiness. Mass production demanded the shift. Universal happiness keeps the wheels steadily turning; truth and beauty can’t. And, of course, whenever the masses seized political power, then it was happiness rather than truth and beauty that mattered. Still, in spite of everything, unrestricted scientific research was still permitted. People still went on talking about truth and beauty as though they were the sovereign goods. Right up to the time of the Nine Years’ War. That made them change their tune all right. What’s the point of truth or beauty or knowledge when the anthrax bombs are popping all around you? That was when science first began to be controlled—after the Nine Years’ War. People were ready to have even their appetites controlled then. Anything for a quiet life. We’ve gone on controlling ever since. It hasn’t been very good for truth, of course. But it’s been very good for happiness. One can’t have something for nothing. Happiness has got to be paid for.’”

“‘It’s curious,’ he went on after a little pause, ‘to read what people in the time of Our Ford used to write about scientific progress. They seemed to have imagined that it could be allowed to go on indefinitely, regardless of everything else. Knowledge was the highest good, truth the supreme value; all the rest was secondary and subordinate. True, ideas were beginning to change even then. Our Ford himself did a great deal to shift the emphasis from truth and beauty to comfort and happiness. Mass production demanded the shift. Universal happiness keeps the wheels steadily turning; truth and beauty can’t. And, of course, whenever the masses seized political power, then it was happiness rather than truth and beauty that mattered. Still, in spite of everything, unrestricted scientific research was still permitted. People still went on talking about truth and beauty as though they were the sovereign goods. Right up to the time of the Nine Years’ War. That made them change their tune all right. What’s the point of truth or beauty or knowledge when the anthrax bombs are popping all around you? That was when science first began to be controlled—after the Nine Years’ War. People were ready to have even their appetites controlled then. Anything for a quiet life. We’ve gone on controlling ever since. It hasn’t been very good for truth, of course. But it’s been very good for happiness. One can’t have something for nothing. Happiness has got to be paid for.’”

Aldous Huxley, Brave New World

My entire Wall Street Journal drama column is devoted to the premiere of Bonnie J. Monte’s new adaptation of Ben Jonson’s The Alchemist. Here’s an excerpt.

* * *

Ben Jonson, Shakespeare’s great contemporary, is well remembered and frequently performed in England, but he’s only a name—if that—to the average American theatergoer. “The Alchemist,” by common consent the best of his verse comedies, doesn’t seem to have received a major production over here since the Shakespeare Theatre Company of Washington, D.C., gave it a poorly received modern-dress revival in 2009. It’s not hard to see why, either. Not only is an uncut performance of “The Alchemist” about four hours long, but Johnson’s flamboyantly archaic diction (“Thou look’st like antichrist, in that lewd hat”) is often more challenging to modern audiences than anything you’re likely to stumble across in Shakespeare.

For these reasons, Bonnie J. Monte’s brand-new adaptation of Jonson’s 1610 tale of a trio of unscrupulous London conpersons, which is currently being performed by the Shakespeare Theatre of New Jersey, is of obvious interest. More on the text in a moment, but the bottom line is that it works, and that Ms. Monte, the company’s artistic director, has treated “The Alchemist” to a staging whose frank bawdiness and knockabout comic vigor are tremendously appealing.

The title of “The Alchemist” refers to Subtle (Bruce Cromer), a phony scientist-magician who claims to have discovered the fabled “philosopher’s stone” that will change base metals into gold. He sets up shop with Face (Jon Barker), an unscrupulous butler, and Dol Common (Aedin Moloney), a woman of more than usually easy virtue, in a vacant London townhouse wherein the trio endeavors to mulct a parade of pigeons out of all they’ve got….

The title of “The Alchemist” refers to Subtle (Bruce Cromer), a phony scientist-magician who claims to have discovered the fabled “philosopher’s stone” that will change base metals into gold. He sets up shop with Face (Jon Barker), an unscrupulous butler, and Dol Common (Aedin Moloney), a woman of more than usually easy virtue, in a vacant London townhouse wherein the trio endeavors to mulct a parade of pigeons out of all they’ve got….

The latter-day appeal of Jonson’s plot needs no explaining, and Ms. Monte has made it more accessible not by updating “The Alchemist” but by cutting and compressing the text (this production runs for a bit more than two and a half hours) and modernizing the language without leaching away its period flavor….

Toffee-nosed purists will look askance at what Ms. Monte has done to “The Alchemist,” but Elizabethan comedies are meant to be seen, not read, and unless you’re already closely familiar with the play, I can’t imagine that you’ll have any serious objections to this full-blooded production, in which the laughs hurtle by like a runaway bullet train. Ms. Moloney, an accomplished stage comedienne whose pungent performance in the Irish Repertory Theatre’s 2011 revival of Brian Friel’s “Dancing at Lughnasa” caught my eye and ear, is no less memorable here as the hoydenish, rough-voiced Dol, whose charms are a function of her availability….

* * *

Read the whole thing here.

| M | T | W | T | F | S | S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | ||||

| 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

| 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 |

| 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 |

| 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 | |

An ArtsJournal Blog