“Carl said his dad knew how to live; he watched the world go by but only paid attention to certain parts.”

“Carl said his dad knew how to live; he watched the world go by but only paid attention to certain parts.”

Elmore Leonard, The Hot Kid

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City

• I’ve been rereading Jeanine Basinger’s The Star Machine, one of the smartest and most illuminating books ever written about studio-era Hollywood. It contains an especially good chapter about Mickey Rooney in which Basinger tells the fascinating story of how A Family Affair, the first Andy Hardy movie, made him a child star in 1937. It wasn’t intended to do any such thing: MGM was grooming another actor in the film, Eric Linden, for stardom. But the public, as is so often the case, drew its own conclusions, which Basinger sums up in two pointed sentences: “Today, no one has heard of Eric Linden. Everybody knows Mickey Rooney.”

Well…yes and no. Rooney was a big, big star until he joined the Army in 1944, but when he returned to Hollywood two years later, it was all over. While he continued to work to the very end of his long life—his last film, Night at the Museum: Secret of the Tomb, will be released in December, seven months after he died at the age of ninety-three—he never again played a leading role in a movie of any great distinction. Nor were very many of his supporting parts noteworthy, though Rooney did manage to transform himself into a character actor of no small accomplishment, as can be seen in the 1962 film version of Rod Serling’s Requiem for a Heavyweight. And while his obituaries were both lengthy and respectful, I suspect that their length was more a matter of his longevity (he was one of the last survivors of the studio system) than anything else. Wonderful though he was in them, scarcely anybody now watches the movies that Rooney made in the Thirties and early Forties, not even the fluffy let’s-put-on-a-show musicals in which he co-starred with Judy Garland, and I can’t imagine that very many people under the age of sixty have more than a vague idea of who he was, much less why it mattered.

Even more interesting to me, however, was something that I learned from the Rooney chapter in The Star Machine, which is that one of his co-stars in A Family Affair was Julie Haydon, who played his sister. Unless you know a lot about the history of Broadway, you won’t recognize Haydon’s name, for she appeared in only a handful of films, none of them particularly noteworthy. It was as a stage actress that she made her name, such as it was, and she is now best known to history for having been the longtime girlfriend and eventual wife of George Jean Nathan, the stiletto-tongued drama critic who co-founded the American Mercury with H.L. Mencken and was the real-life model for Addison DeWitt, the venomous critic played by George Sanders in All About Eve. (For the record, Lillian Gish preceded her in Nathan’s bed.)

It was widely taken for granted on Broadway that Haydon got cast in plays because of her relationship with Nathan, which was an open secret, so much so that Damon Runyon is said to have had them in mind when he created the characters of Miss Adelaide and Nathan Detroit in the short story that Abe Burrows and Frank Loesser later turned into into Guys and Dolls.

It was widely taken for granted on Broadway that Haydon got cast in plays because of her relationship with Nathan, which was an open secret, so much so that Damon Runyon is said to have had them in mind when he created the characters of Miss Adelaide and Nathan Detroit in the short story that Abe Burrows and Frank Loesser later turned into into Guys and Dolls.

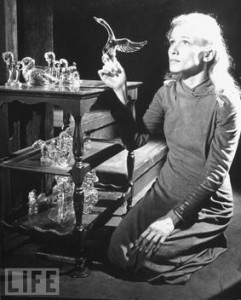

On the other hand, she received reviews that were much more than merely respectful throughout her comparatively brief stage career, and she also created the role of Laura Wingfield in the original production of The Glass Menagerie. No matter whom she knew, it’s hard to imagine that she would have landed that demanding part had she not been competent enough to play opposite Laurette Taylor, the first Amanda, who gave what is universally regarded as one of the greatest performances in the history of the American stage. As for Haydon, no less qualified an observer than Stark Young, that toughest and most knowing of critical customers, wrote in The New Republic that she gave “one of her translucent performances of a dreaming, wounded, half-out-of-this-world young girl.”

Haydon got a much shorter New York Times obituary of her own when she died in 1994. It decorously overlooked the precise nature of her relationship with Nathan, and devoted one sentence to her film career. And that was that: now she belongs to the ages, and the ages don’t seem to care much for her. Or for Mickey Rooney, sad to say. Nostalgia only lasts as long as the people who feel it are still alive, and its value depreciates with fearful velocity. Few things are more ephemeral than the fame of a movie star who didn’t make any great movies—unless it’s the reputation of a stage actor who didn’t play any great film roles. Try though she might, not even a historian as fine as Jeanine Basinger can do much of anything about that.

Haydon got a much shorter New York Times obituary of her own when she died in 1994. It decorously overlooked the precise nature of her relationship with Nathan, and devoted one sentence to her film career. And that was that: now she belongs to the ages, and the ages don’t seem to care much for her. Or for Mickey Rooney, sad to say. Nostalgia only lasts as long as the people who feel it are still alive, and its value depreciates with fearful velocity. Few things are more ephemeral than the fame of a movie star who didn’t make any great movies—unless it’s the reputation of a stage actor who didn’t play any great film roles. Try though she might, not even a historian as fine as Jeanine Basinger can do much of anything about that.

* * *

Mickey Rooney and Margaret Marquis in a scene from A Family Affair:

Mickey Rooney and Jackie Gleason in a scene from the film version of Requiem for a Heavyweight:

Today’s Wall Street Journal drama column is devoted in its entirety to Westport Country Playhouse’s revival of Alan Ayckbourn’s Things We Do for Love. Here’s an excerpt.

* * *

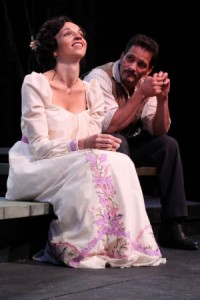

Alan Ayckbourn has no better institutional friend in America than Connecticut’s Westport Country Playhouse, which has staged nine of his 78 plays to date. The latest one is the company’s current production, “Things We Do for Love,” a four-character comedy from 1997 that is rarely performed in this country and which I saw for the first time ever on Saturday. The reason why it doesn’t get done much is obvious: “Things We Do for Love” calls for a three-story set, a feat of scenic trickery beyond the means of most regional troupes.

Fortunately, Westport Country Playhouse, whose 578-seat auditorium is handily equipped with an orchestra pit, is up to the challenge, and John Tillinger’s production reveals “Things We Do for Love” to be a play of no small emotional complexity—cunningly disguised as a who’s-been-sleeping-in-my-bed farce….

Let’s start with the hijinks-encrusted plot. Barbara (Geneva Carr) rents out her basement and upstairs bedroom, the first to Gilbert (Michael Mastro), a wimpy, lower-middle-class handyman, and the second to Nikki (Sarah Manton), Barbara’s younger friend and former classmate, and Hamish (Matthew Greer), Nikki’s hunky fiancé. That’ll give you an inkling of what happens next: Barbara and Hamish end up in the sack, much to the horror of Nikki and the dismay of Gilbert, who harbors a hopeless crush on his landlady.

Let’s start with the hijinks-encrusted plot. Barbara (Geneva Carr) rents out her basement and upstairs bedroom, the first to Gilbert (Michael Mastro), a wimpy, lower-middle-class handyman, and the second to Nikki (Sarah Manton), Barbara’s younger friend and former classmate, and Hamish (Matthew Greer), Nikki’s hunky fiancé. That’ll give you an inkling of what happens next: Barbara and Hamish end up in the sack, much to the horror of Nikki and the dismay of Gilbert, who harbors a hopeless crush on his landlady.

The results are shriekingly funny—at first. But Mr. Ayckbourn’s characters aren’t stick figures, nor have they earned the abject humiliation that is the engine of traditional farce. Barbara is a fortyish spinster with a sharp tongue who lives alone and hates it, while Nikki is a cheery little twit who goes in for men who beat her up….

Mr. Tillinger, who has previously staged Mr. Ayckbourn’s “How the Other Half Loves,” “Relatively Speaking” and “Time of My Life” at Westport, knows well that his sad farces don’t work unless they’re played yardstick-straight. If you telegraph the comic punches, you’ll end up with forced, uncomfortable laughter. That never happens in “Things We Do for Love.” Ms. Carr’s performance, in particular, is quite unusually subtle, far more than you’d expect in a play whose climax is a wild explosion of slapstick violence….

* * *

Read the whole thing here.

In today’s Wall Street Journal “Sightings” column, I comment on the last-minute settlement of the Metropolitan Opera’s labor negotations. Here’s an excerpt.

* * *

The show goes on. Instead of locking out the Metropolitan Opera’s musicians and stagehands, Peter Gelb, the company’s general manager, agreed to a still-to-be-ratified settlement with their labor unions that will allow America’s biggest opera company to open its 2014-15 season on schedule.

Beyond expressing relief that the Met didn’t have to scuttle its season, few observers have said much about the specifics of the settlement. Presumably this is because they were not officially released to the press. But they were widely leaked, and it isn’t hard to figure out how Mr. Gelb and the unions managed to get to yes. What’s more, it appears that the terms to which the general manager agreed stand in sharp contrast to what he’d argued was necessary to pull the Met out of its financial quicksand. The company, he claimed, was galloping toward the abyss, and only the most drastic reforms could save it. “No cuts means no Met,” he said….

Beyond expressing relief that the Met didn’t have to scuttle its season, few observers have said much about the specifics of the settlement. Presumably this is because they were not officially released to the press. But they were widely leaked, and it isn’t hard to figure out how Mr. Gelb and the unions managed to get to yes. What’s more, it appears that the terms to which the general manager agreed stand in sharp contrast to what he’d argued was necessary to pull the Met out of its financial quicksand. The company, he claimed, was galloping toward the abyss, and only the most drastic reforms could save it. “No cuts means no Met,” he said….

I claim no inside knowledge of the Met, but it looks to me as though one of two things has happened: Either Mr. Gelb exaggerated the company’s plight as a negotiating tactic, or the unions ate his lunch….

* * *

Read the whole thing here.

“I read poems, and I think, Yes, that’s quite a nice idea, but why can’t he make a poem of it? Make it memorable? It’s no good just writing it down! At any level that matters, form and content are indivisible. What I meant by content is the experience the poem preserves, what it passes on. I must have been seeing too many poems that were simply agglomerations of words when I said that.”

“I read poems, and I think, Yes, that’s quite a nice idea, but why can’t he make a poem of it? Make it memorable? It’s no good just writing it down! At any level that matters, form and content are indivisible. What I meant by content is the experience the poem preserves, what it passes on. I must have been seeing too many poems that were simply agglomerations of words when I said that.”

Philip Larkin, Paris Review interview, Summer 1982 (courtesy of Patrick Kurp)

Here’s my list of recommended Broadway, off-Broadway, and out-of-town shows, updated weekly. In all cases, I gave these shows favorable reviews (if sometimes qualifiedly so) in The Wall Street Journal when they opened. For more information, click on the title.

BROADWAY:

• Cabaret (musical, PG-13/R, nearly all performances sold out last week, closes Jan. 4, reviewed here)

• A Gentleman’s Guide to Love & Murder (musical, PG-13, all performances sold out last week, reviewed here)

• Matilda (musical, G, all performances sold out last week, reviewed here)

• Les Misérables (musical, G, too long and complicated for young children, reviewed here)

• Once (musical, G/PG-13, reviewed here)

OFF BROADWAY:

• The Fantasticks (musical, G, suitable for children capable of enjoying a love story, reviewed here)

IN NIAGARA-ON-THE-LAKE, ONTARIO:

• Arms and the Man (comedy, G/PG-13, closes Oct. 18, reviewed here)

• The Sea (black comedy, PG-13, closes Oct. 26, closes Oct. 12, reviewed here)

• When We Are Married (comedy, PG-13, closes Oct. 26, reviewed here)

IN SPRING GREEN, WIS.:

• The Doctor’s Dilemma (comedy, G/PG-13, closes Oct. 3, reviewed here)

• The Seagull (drama, G/PG-13, closes Sept. 20, reviewed here)

• The Seagull (drama, G/PG-13, closes Sept. 20, reviewed here)

CLOSING THIS WEEKEND IN GARRISON, N.Y.:

• The Liar (verse comedy, PG-13, closes Sunday, reviewed here)

• Othello (Shakespearean tragedy, PG-13, closes Saturday, reviewed here)

• Two Gentlemen of Verona (Shakespearean comedy, PG-13, closes Friday, reviewed here)

CLOSING SUNDAY IN MADISON, N.J..:

• The Alchemist (verse comedy, PG-13, reviewed here)

| M | T | W | T | F | S | S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | ||||

| 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

| 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 |

| 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 |

| 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 | |

An ArtsJournal Blog