I spent much of last week in West Palm Beach, where I saw a show, gave two talks, and paid a quick visit to the Norton Museum of Art, which has mounted an unassuming yet noteworthy exhibition of forty works on paper called Master Prints: Dürer to Matisse. The prints, all of which are owned by discreetly anonymous lenders, were well chosen—I’ve never seen so many first-class Rembrandt etchings in a single gallery—and in immaculate condition.

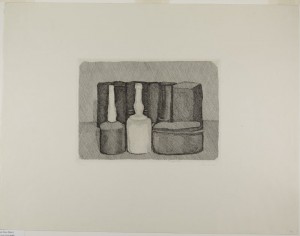

I was especially interested in a 1954 etching by Giorgio Morandi that I’d only seen reproduced in catalogues. You can’t fully appreciate the texture and depth of a great etching until you see it “in the flesh,” so to speak, and this one ranks among Morandi’s finest. Having once tried and failed to buy a Morandi etching at auction, I was briefly incapacitated by envy of the unknown owner, but I soon got over it and marveled at the quiet beauty of “Still Life with Nine Objects.”

I was especially interested in a 1954 etching by Giorgio Morandi that I’d only seen reproduced in catalogues. You can’t fully appreciate the texture and depth of a great etching until you see it “in the flesh,” so to speak, and this one ranks among Morandi’s finest. Having once tried and failed to buy a Morandi etching at auction, I was briefly incapacitated by envy of the unknown owner, but I soon got over it and marveled at the quiet beauty of “Still Life with Nine Objects.”

To quote what I wrote in the Washington Post ten years ago about an exceptionally impressive Morandi exhibition:

The effect of this show is wildly disproprtionate to its minuscule size: six oil paintings and two works on paper, all of them still lifes and none in any obvious way imposing. Yet as you look at how the greatest Italian artist of the 20th century painstakingly arranged and rearranged a dozen bottles, bowls and boxes on a table and painted them over and over again, you find yourself whisked out of the grinding noise of everyday urban life and spirited away to a place of intense stillness. It’s as if a soft-spoken man had slipped discreetly into a small room open to the public, whispering life-changing confidences to the fortunate few who visit him there.

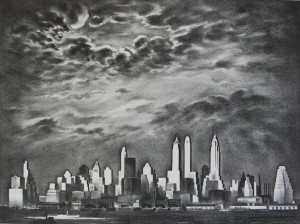

One of the reasons why I wanted to see Master Prints: Dürer to Matisse is that Mrs. T and I also collect prints, albeit on a far more modest scale. The day after I flew back to New York, I picked up our newly framed copy of Childe Hassam’s “Storm King” and brought it home. I’d originally planned to hang it directly above John Twachtman’s “Dock at Newport,” but Mrs. T, who has a sharp eye, gave me a better idea, and so “Storm King” now shares a wall with “Storm Over Manhattan,” a 1936 lithograph by Louis Lozowick (reproduced at right) for which she has a special liking.

One of the reasons why I wanted to see Master Prints: Dürer to Matisse is that Mrs. T and I also collect prints, albeit on a far more modest scale. The day after I flew back to New York, I picked up our newly framed copy of Childe Hassam’s “Storm King” and brought it home. I’d originally planned to hang it directly above John Twachtman’s “Dock at Newport,” but Mrs. T, who has a sharp eye, gave me a better idea, and so “Storm King” now shares a wall with “Storm Over Manhattan,” a 1936 lithograph by Louis Lozowick (reproduced at right) for which she has a special liking.

On Sunday I read an essay about materialism in which Arthur Brooks made the following observation:

In the realm of material things, attachment results in envy and avarice. Getting beyond these snares is critical to life satisfaction. But how to do it?…

First, collect experiences, not things.

Material things appear to be permanent, while experiences seem evanescent and likely to be forgotten. Should you take a second honeymoon with your spouse, or get a new couch? The week away sounds great, but hey—the couch is something you’ll have forever, right?

Wrong. Thirty years from now, when you are sitting in rocking chairs on the porch, you’ll remember your second honeymoon in great detail. But are you likely to say to one another, “Remember that awesome couch?” Of course not. It will be gone and forgotten. Though it seems counterintuitive, it is physically permanent stuff that evaporates from our minds. It is memories in the ether of our consciousness that last a lifetime, there for us to enjoy again and again.

Of course I see what Brooks is getting at, and up to a point I agree with him (though I’d be more inclined to take his reflections on the problem of materialism seriously had he not gone well out of his way to explain how they were inspired by “a recent trip to India”). Over the weekend Mrs. T and I went to Ecce Bed and Breakfast, the rural retreat where we spent our honeymoon, and we expect that both of those blissful experiences will last us a lifetime. On the other hand, Arthur Brooks also sounds like the kind of person who’s never really looked at a painting. Buying an awesome lithograph is not the same thing as buying an awesome couch. Sometimes things are experiences.

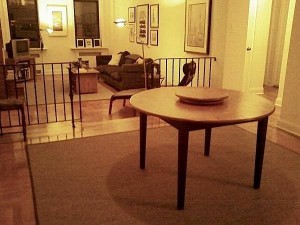

In 2004, a year after I started buying works on paper, I wrote an essay for Commentary in which I described the experience of living with art:

In 2004, a year after I started buying works on paper, I wrote an essay for Commentary in which I described the experience of living with art:

Whatever my reservations—and no collector is ever entirely satisfied—I am happy with the Teachout Museum just as it is. Not only is it a joy to behold, but its beauties have had the beneficial effect of making me want to spend less time rattling around Manhattan, fulfilling the hectic duties of a freelance critic, and more time sitting in my living room, communing with the works of art I have so carefully assembled. Whether it will help me to live longer is an open question, but collecting art, even on a modest scale, has definitely made my interior life richer than ever before.

While the Teachout Museum has doubled in size since I wrote “Living With Art,” my feelings about it remain unchanged. I would never dream of pretending that it’s a bigger deal than it is, but when I returned to our apartment after freshening my eye by spending an afternoon looking at Master Prints: Dürer to Matisse, I felt quite proud of our little collection. Yes, Mrs. T and I put it together on a shoestring, but it was assembled with painstaking thought and much love, and I can’t imagine anyone getting more life-changing pleasure out of the art on their walls than we do from ours. If this be materialism, make the most of it.