I recently saw a small-town Nutcracker danced by an ensemble of Connecticut students. I don’t usually have occasion to attend such homely events, but I had a horse in the race—Ian, my nephew, played Dr. Stahlbaum, the genial host of the first-act party scene—and I was curious to find out what America’s best-loved ballet looks like when done by amateurs. You can always learn from watching an amateur theatrical performance, just as you can learn a lot about what it means for a painting to be of “museum quality” by looking at the not-quite-masterpieces by major artists that hang in so many of America’s smaller regional museums. So Mrs. T and I went to Ian’s Nutcracker, and though we were admittedly present as an act of pure family loyalty, I ended up getting quite a bit more out of it than I expected.

I recently saw a small-town Nutcracker danced by an ensemble of Connecticut students. I don’t usually have occasion to attend such homely events, but I had a horse in the race—Ian, my nephew, played Dr. Stahlbaum, the genial host of the first-act party scene—and I was curious to find out what America’s best-loved ballet looks like when done by amateurs. You can always learn from watching an amateur theatrical performance, just as you can learn a lot about what it means for a painting to be of “museum quality” by looking at the not-quite-masterpieces by major artists that hang in so many of America’s smaller regional museums. So Mrs. T and I went to Ian’s Nutcracker, and though we were admittedly present as an act of pure family loyalty, I ended up getting quite a bit more out of it than I expected.

As we settled into our seats and the taped sounds of Tchaikovsky’s “Miniature Overture” filled the auditorium, I realized with a start that it had been well over a decade since I’d last been to a live performance of The Nutcracker. Back in my dance-critic days, I used to see New York City Ballet do George Balanchine’s 1954 version two or three times each season, and I also went out of my way to catch The Hard Nut, Mark Morris’ updated Nutcracker, whenever it came to New York. Alas, I now spend so many of my evenings seeing plays that I don’t have time to go to the ballet other than sporadically, and on the rare occasions when I do, The Nutcracker isn’t high on my list of priorities. Yet I don’t see why it shouldn’t be, for Balanchine’s Nutcracker is one of his greatest achievements, a genuinely popular work of art that is also a top-tier masterpiece.

It was, I suppose, inevitable that some art-hating moron would eventually get around to decrying the alleged “racism” of the gentle national stereotypes that Balanchine uses with the utmost affection in his second-act character dances. Far more interesting, in any case, is the first-act pantomime scene, an idealized stage version of a family Christmas party that Arlene Croce famously praised for its “seductive blend, so typically Balanchinean, of real fantasy and fantastic realism.”

It was, I suppose, inevitable that some art-hating moron would eventually get around to decrying the alleged “racism” of the gentle national stereotypes that Balanchine uses with the utmost affection in his second-act character dances. Far more interesting, in any case, is the first-act pantomime scene, an idealized stage version of a family Christmas party that Arlene Croce famously praised for its “seductive blend, so typically Balanchinean, of real fantasy and fantastic realism.”

That scene comforted me when, a quarter-century ago, the inexorable press of work forced me to spend Christmas alone in New York, the one and only time in my entire life when I’ve been away from my family for the holidays. I described the occasion a few years after the fact in a memoir of my small-town childhood and youth:

I popped a frozen pizza into the oven and went into the living room, which was bereft of Christmas decorations. (It is as hard to put up a Christmas tree for yourself as it is to cook for yourself.) I put on a record of The Nutcracker. Then I curled up on the couch with my cats, my presents, and my tin of cookies and thought about the Nutcracker I had seen at Lincoln Center a few days before. Something told me that watching The Nutcracker in a theater full of children would cheer me up, so I chose a Saturday matinee. Kyra Nichols, my favorite ballerina, was dancing that afternoon, and I expected to enjoy myself. I did, too, but not in the way I had expected. George Balanchine’s version of The Nutcracker begins with a Christmas Eve family party. The setting is a large, homey-looking living room filled with children who exchange presents, play leapfrog, and chase each other around. As the curtain went up and the children began to play, my eyes filled with tears. It was all so familiar. It had all been such a long time ago.

I thought of that far-off matinee as I watched the first act of The Nutcracker in Connecticut. Of course I love it because it reminds me of the wonderful Christmas-eve parties that my mother’s family gave each year, but I admire it for other, more specifically aesthetic reasons. “For years Balanchine’s Act I has been taken for granted because it’s so simple and ‘has no dancing,’” Arlene Croce wrote in 1974. “It contains the heart of his genius.” So it does, and Amy Chibeau staged her own version with a clarity and solidity that reminded me of just how conceptually strong the party scene is, whether in Balanchine’s now-iconic version or in alternate versions that bear his unmistakable stamp.

I thought of that far-off matinee as I watched the first act of The Nutcracker in Connecticut. Of course I love it because it reminds me of the wonderful Christmas-eve parties that my mother’s family gave each year, but I admire it for other, more specifically aesthetic reasons. “For years Balanchine’s Act I has been taken for granted because it’s so simple and ‘has no dancing,’” Arlene Croce wrote in 1974. “It contains the heart of his genius.” So it does, and Amy Chibeau staged her own version with a clarity and solidity that reminded me of just how conceptually strong the party scene is, whether in Balanchine’s now-iconic version or in alternate versions that bear his unmistakable stamp.

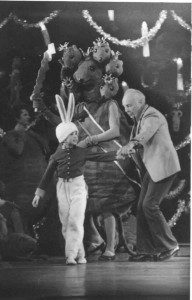

For the record, my nephew was a very good Stahlbaum, unselfconsciously serious and completely immersed in his part. The second-act dancing was inevitably uneven, but I was as charmed by the children in the cast as were their doting parents, and Tchaikovsky’s gorgeous score took up the slack whenever things went askew on stage or backstage.

“You know, I’m really surprised how much I enjoyed myself today,” I said to Mrs. T as we drove home after the show.

“I’m not,” she replied. “I saw you crying during the first act.”

* * *

The opening scene from New York City Ballet’s 1993 film of The Nutcracker, choreographed by George Balanchine and directed by Emile Ardolino, with Robert LaFosse and Heather Watts as the Stahlbaums: